I'll load all the prep for the semester on this page (soon).

Prep.Day1

There was no prep for the first day of class. Welcome to Math 214.

Prep.Day2

Task 2.1

Start by looking up the terms vector-valued function and vector parameterization of a curve.

- Write definitions in your own words for the terms above.

- For each vector parameterization below, construct a graph of the curve. [Hint: make a table of points if needed, including $t$, $x$, and $y$, and then just plot the $(x,y)$ coordinates).

- $\vec r(t) = \left< 2t+1, 4-3t\right>$ for $0\leq t\leq 2$.

- $(x,y) = (\cos t, \sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 3\pi/2$.

- $(x,y)(t) = (\sin t, \cos t)$ for $0\leq t\leq \pi$.

- $\langle x,y,z\rangle = (2\cos t, 2\sin t, t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 4\pi$.

Task 2.2

Start by locating a definition of the dot product of two vectors and what it means for two vectors to be orthogonal, as well as the dot product form of the law of cosines.

- Compute the dot product of the two vectors $\vec a = 3\vec i-4\vec j+2\vec k$ and $\vec b = (-1,3,6)$.

- Find the angle between $\vec a$ and $\vec b$.

- Give a value $k$ so that the vectors $\vec a = 3\vec i-4\vec j+2\vec k$ and $\vec c = \langle 2, -1, k\rangle$ are orthogonal.

- A car is moving in the direction $\vec v = (-5,7)$. The car makes a 90 degree turn to the left. Give a vector that is parallel to this new direction of motion.

Task 2.3

Start by looking up the definition of a unit vector. Consider the two points $P = (1, 2, 3)$ and $Q = (2, −1, 0)$.

- Write the vector $\vec {PQ} $ in component form $(a, b, c)$.

- Find the length of vector $\vec {PQ} $.

- Find a unit vector in the same direction as $\vec {PQ} $.

- Find a vector of length 7 units that points in the same direction as $\vec {PQ} $.

Task 2.4

The last problem for prep each day will point to relevant problems from OpenStax. Spend 30 minutes working on problems from the sections below.

- In section 1.1, complete checkpoints 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3. Use the corresponding examples, if needed, to help you.

- In section 2.3, complete an exercise for each group in 123-144, and then try a few problems in 149-154.

Prep.Day3

Task 3.1

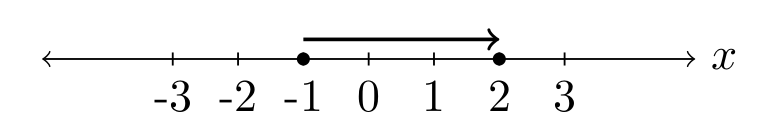

Suppose for a short time that a rover follows a path given by $(x, y) = (1t + 3, −2t + 4)$. This is the same as writing $(x, y) = (1, −2)t + (3, 4)$.

- Construct a plot that shows the location of the rover at time $t = 0, 1, 2$, and add some arrows as well as a line to illustrate the rover’s path.

- What is the speed of the rover? (you may assume that distances are in meters, and time is in minutes).

- What is the rover's velocity (hint, this should be a vector)?

- When we write the path in the form $(x, y) = (1, −2)t + (3, 4)$, what do the quantities (1, −2) and (3, 4) have to do with the path?

- The rover is no longer on flat ground, rather is sitting at point $P = (0, 2, 3)$. It starts to climb in the direction $\vec v = \langle 1, −1, 2\rangle$.

- Write a vector equation $(x, y, z) = (?, ?, ?)$ for the line that passes through the point $P$ and is parallel to $\vec v$.

- Generalize your work to give an equation of the line that passes through the point $P = (x_1 , y_1 , z_1)$ and is parallel to the vector $\vec v = (v_1 , v_2 , v_3 )$.

Task 3.2

Suppose the Curiosity rover travels in a circular path given by the parametric curve $\vec r(t) = (3 \cos t, 3 \sin t)$.

- Graph the curve $\vec r$ (you should obtain a circle) and make sure you designate the direction in which the rover is traveling.

- Compute both $\ds \frac{d \vec r}{dt}$ and $\ds\frac{d^2\vec r}{dt^2}$.

- Locate the point on your graph that the rover is at when $t = \pi/2$. How would you describe the velocity and acceleration of the rover at this point? Compute both $\frac{d\vec r}{dt}(\frac{\pi}{2})$ and $\frac{d^2\vec r}{dt^2}(\frac{\pi}{2})$, and confirm that these vectors do indeed provide the acceleration and velocity of the rover at $t = \pi/2$.

- Let's swap to the time $t = \pi/4$. On your graph, draw the vectors $\frac{d\vec r}{dt}(\frac{\pi}{4})$ and $\frac{d^2\vec r}{dt^2}(\frac{\pi}{4})$ with their tail placed on the curve at $\vec r(\frac{\pi}{4})$. These vectors are the velocity and acceleration.

- Give a vector equation of the tangent line to this curve at $t = \pi/4$.

Task 3.3

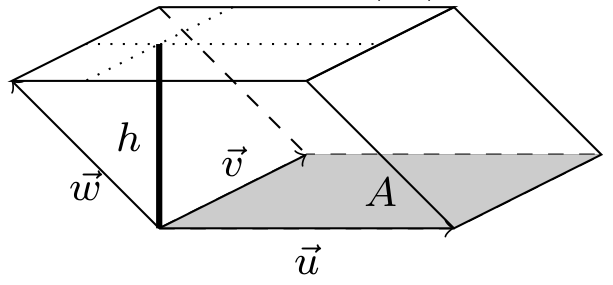

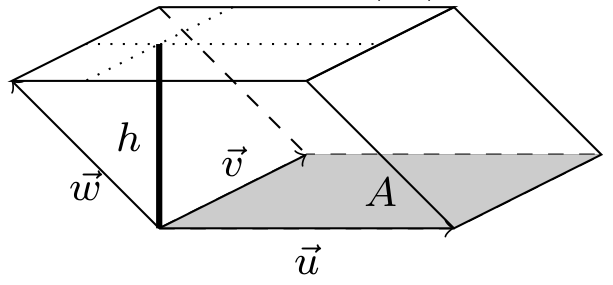

Suppose a heavy box needs to be lowered down a ramp. The box exerts a downward force of say 200 Newtons (gravity), which we could write in vector notation as $\vec F=\left<0,-200\right>$. If the ramp was placed so that the box needed to be moved right 6 m, and down 3 m, then we'd need to get from the origin $(0,0)$ to the point $(6,-3)$. This displacement can be written as $\vec d=\left<6,-3\right>$. The force $\vec F$ acts straight down, rather than parallel to the displacement. Let's find out how much of the force $\vec F$ acts in the direction of the displacement. We are going to break the force $\vec F$ into two components, one component in the direction of $\vec d$, and another component orthogonal to $\vec d$. The component of the force that is parallel to $\vec d$ is useful in understanding energy computations. The component of the force that is orthogonal to $\vec d$ is useful in understanding surface friction.

We want to write $\vec F$ as the sum of two vectors $\vec F = \vec w+\vec n$, where $\vec w$ is parallel to $\vec d$ and $\vec n$ is orthogonal to $\vec d$. Since $\vec w$ is parallel to $\vec d$, we can write $\vec w=c\vec d$ for some unknown scalar $c$. This means that $\vec F=c\vec d+\vec n$.

- Start by drawing a picture that shows how $\vec F$, $\vec d$, $\vec w$, and $\vec n$ are related.

- Use the fact that $\vec n$ is orthogonal to $\vec d$ to show that $\ds c = \frac{\vec F\cdot \vec d}{\vec d\cdot \vec d}$. [Hint: Dot each side of $\vec F=c\vec d+\vec n$ with $\vec d$ and distribute. You'll need to use the fact that $\vec n$ and $\vec d$ are orthogonal to remove $\vec n\cdot \vec d$ from the problem.]

- Now that we have a formula for $c$, use that formula to show that $\vec w = c\vec d = (80,-40)$. We call this the projection of $\vec F$ onto $\vec d$ (or the component of $\vec F$ that is parallel to $\vec d$), and write $$\text{proj}_{\vec d}\vec F = \vec F_{\parallel \vec d}= \left(\frac{\vec F\cdot \vec d}{\vec d\cdot \vec d}\right)\vec d.$$

- Obtain a formula for $\vec n$, the component of the force that is orthogonal to $\vec d$. This is sometimes written as $\vec F_{\perp \vec d}$.

Task 3.4

The last problem for prep each day will point to relevant problems from OpenStax. Spend 30 minutes working on problems from the sections below. Remember that you don't have to do all of the problems listed below, rather do a few from sections that you feel you need more practice with.

- Equations of lines: Section 2.5, checkpoint 2.43 and exercises 243 - 250.

- Derivatives of Vector Valued functions: Section 3.2, checkpoint 3.5 and exercises 41-54.

- Projection practice: section 2.3, checkpoint 2.27 and exercises 167-172

Prep.Day4

Task 4.1

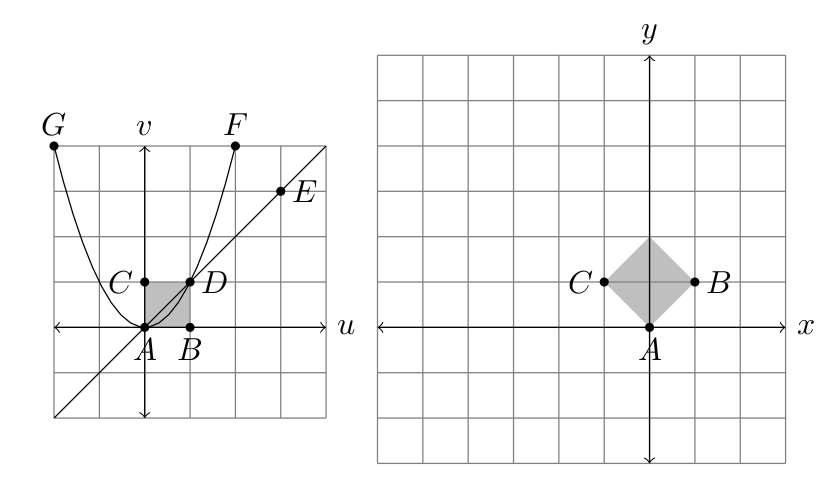

Consider the curve $\vec r(t) = (2t+3, 4(2t-1)^2)$.

- Construct a graph of $\vec r$ for $0\leq t\leq 2$.

- If this curve represents the path of a rover (meters for distance, minutes for time), find the velocity of the rover at any time $t$, and then specifically at $t=1$. What is the rover's speed at $t=1$?

- Give a vector equation of the tangent line to $\vec r$ at $t=1$. Include this on your graph.

- State the rover's acceleration vector.

- Explain how to obtain the slope of the tangent line, and then write an equation of the tangent line using point-slope form. [Hint: How can you turn the direction vector, which involves $(dx/dt)$ and $(dy/dt)$, into the number given by the slope $(dy/dx)$?]

Task 4.2

We are ready to tackle the problem of finding the length of a path. This length we call arc length. If a rover moves at a constant speed, then the distance traveled is simply $$\text{distance} = \text{speed}\times\text{time}.$$ This requires that the speed be constant. What if the speed is not constant? Over a really small time interval $dt$, the speed is almost constant, so we can still use the idea above.

Suppose a rover (or other object) moves along the path given by $\vec r(t)=(x(t),y(t))$ for $a\leq t\leq b$. We know that the velocity is $\dfrac{d\vec r}{dt}$, and so the speed is just the magnitude of this vector.

- Show that we can write the rover's speed at any time $t$ as $$\ds\sqrt{\left(\frac{dx}{dt}\right)^2+\left(\frac{dy}{dt}\right)^2}.$$

- If the rover moves at speed $\ds\sqrt{\left(\frac{dx}{dt}\right)^2+\left(\frac{dy}{dt}\right)^2}$ for a little time length $dt$, what's the little distance $ds$ that the rover traveled?

- Explain (Riemann sums may help) why the length of the path given by $\vec r(t)$ for $a\leq t\leq b$ is $$s=\int ds=\int_a^b \left|\frac{d\vec r}{dt}\right| dt=\int_a^b \sqrt{\left(\frac{dx}{dt}\right)^2+\left(\frac{dy}{dt}\right)^2}dt.$$

- The path $\vec r(t) = (3\cos t, 3\sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 2\pi$ is a circle of radius 3. Verify that the formula above does in fact yield the circumference of this circle.

- If the curve is in space (so $\vec r(t)=(x(t),y(t),z(t))$ is the path), then how does the arc length formula above change?

- Are there any requirements we must know about the parametrization $\vec r$ so that the formula above is valid?

Task 4.3

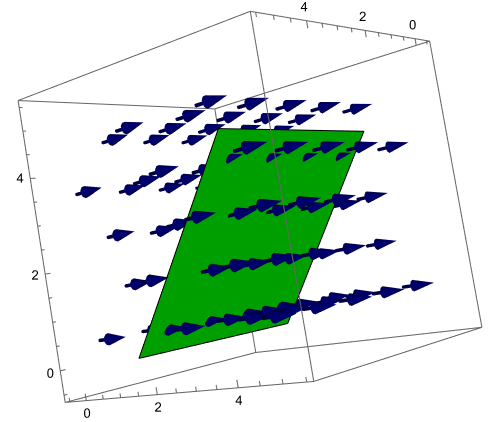

Gravity is often the first example we encounter of a vector field. Other important vector fields arise when we study magnetism, electricity, fluid flow, and more. To analyze how a river flows, we can construct a plot of the river and at each point in the river we draw a vector that represents the velocity at that point. This creates a collection of many vectors drawn all at once, where the base of each velocity vector is placed at the point where the velocity occurs. For gravity, a similar picture can be drawn, though all the vectors will point down with the same magnitude. This task has us construct a plot of a vector field.

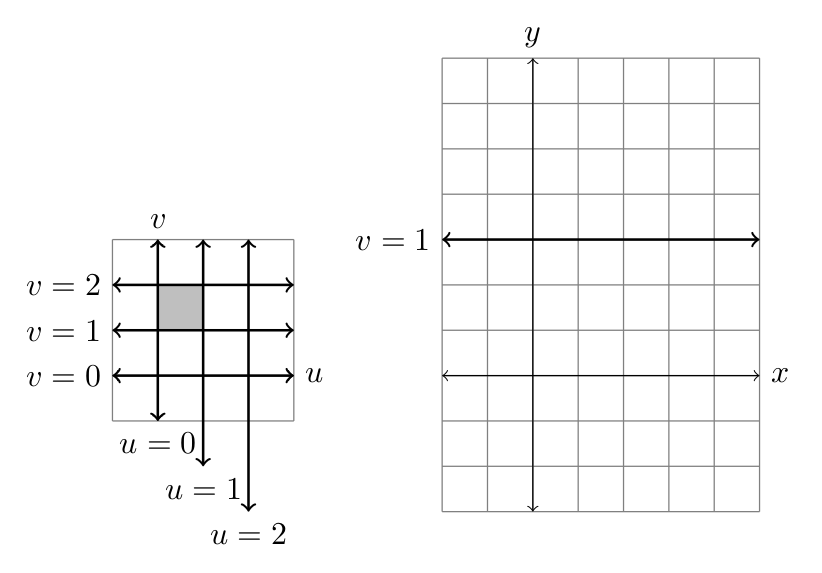

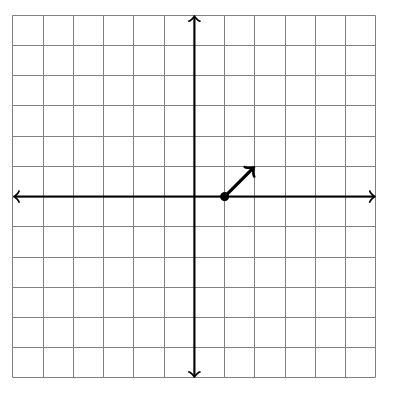

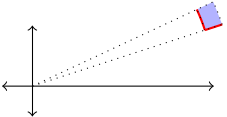

Consider the function $\vec F(x,y) = \left<x-2y,x+y\right>$. This is a function where the input is a point $(x,y)$ in the plane, and the output is the vector $\left<x-2y,x+y\right>$. For example, if we input the point $(1,0)$, then the output is $\left<1-2(0),1+0\right> = \left<1,1\right>$. To construct a vector field plot, we draw the vector $\left<1,1\right>$ with its base located at the input $(1,0)$. In the picture below, based at $(1,0)$ we draw a vector that points right 1 and up 1.

- Complete the table below and add the other 7 vectors to the graph.

\(\begin{array}{c|c} (x,y)&\left<x-2y,x+y\right>\\\hline (1,0)&\left<1,1\right>\\ (1,1)&\\ (1,-1)&\\ (0,1)&\\ (0,-1)&\\ (-1,0)&\\ (-1,1)&\\ (-1,-1)& \end{array}\)

- Repeat the above for the vector field $\vec F(x,y)=(-2y,3x)$, constructing a vector field plot consisting of 8 vectors.

Task 4.4

The last problem for prep each day will point to relevant problems from OpenStax. Spend 30 minutes working on problems from the sections below.

- section 3.2: checkpoint 3.7, exercises 75-92

- Arc Length Practice: section 3.3: checkpoint 3.9, exercises 102-112

Prep.Day5

Task 5.1

Work is a transfer of energy. When a force acts through a displacement, work is done. Gravity acts on falling objects, transferring potential energy to kinetic energy. Any force, when acting through a displacement, will result work done.

- When a constant force and displacement are in the same straight line direction, the work done is simply the product of the magnitude of the force, and the distance.

- When a constant force acts opposite a straight line displacement, the work is the negative of the magnitude of the force and the distance.

If a constant force is not parallel (or antiparallel) to a straight line displacement $\vec d$, then we instead use the component of the force that is parallel to the displacement (so $\vec F_{\parallel \vec d}$) to compute work.

Let $\vec F=(-1,2)$ and $\vec d=(3,4)$.

- Start by computing $\vec F_{\parallel d} = \text{proj}_{\vec d}\vec F$ and $\vec F_{\perp d}$.

- Construct a picture that shows the relationship between $\vec F,$ $\vec d$, $\text{proj}_{\vec d}\vec F$, and $\vec F_{\perp d}$.

- Compute the work done by $\vec F$ through the displacement $\vec d$ by computing $|\vec F_{\parallel d}|$ and $|\vec d|$. Should the work be positive or negative?

Change the force to $\vec F = (-2,0)$. but keep $\vec d=(3,4)$.

- Construct a similar picture as above, showing the relationship between $\vec F,$ $\vec d$, $\text{proj}_{\vec d}\vec F$, and $\vec F_{\perp d}$. Feel free to construct this picture with, or without, doing any computations.

- Compute the work done by $\vec F$ through the displacment $\vec d$. Should the work be positive or negative?

- Can you find a simpler way to compute the work done by $\vec F$ through $\vec d$ than computing $|\vec F_{\parallel d}|$ and $|\vec d|$?

Task 5.2

- Find the length of the curve $\ds \vec r(t) = \left(t^3,\frac{3t^2}{2}\right)$ for $t\in[1,3]$. The notation $t\in[1,3]$ means $1\leq t\leq 3$. Be prepared to show us your integration steps in class (you'll need a substitution).

- Now find the length of the helix $\vec r(t) = (2\cos t, 2\sin t, t)$ for $t\in [0, 4\pi] $.

Task 5.3

Suppose a rover is currently moving and has a velocity vector $\vec v = (3,4)$. A force acts on the rover causing an acceleration of $\vec a = (-1,5)$. The rover is currently at the location $(2,-3)$.

- Draw picture that shows the rover's location along with the velocity and acceleration vectors drawn with their base at the rover's location.

- Find the vector component of the acceleration that is parallel to the velocity (so find $\vec a_{\parallel \vec v}$), and then find the vector component of the acceleration that is orthogonal to the velocity (so find $\vec a_{\perp \vec v}$).

- Will this acceleration cause the rover to speed up or slow down? Explain.

- Will this acceleration cause the rover to turn left or right? Explain.

A probe above Mars is currently moving and has a velocity vector $\vec v = (-2,1,2)$. The onboard thrusters apply a force that causes an acceleration of $\vec a = (0,2,-3)$.

- Find both $\vec a_{\parallel \vec v}$ and $\vec a_{\perp \vec v}$.

- Will this acceleration cause the satellite to speed up or slow down? Explain.

- How would you interpret $\vec a_{\perp \vec v}$?

Task 5.4

The last problem for prep each day will point to relevant problems from OpenStax. Spend 30 minutes working on problems from the sections below.

- Work: section 2.3, checkpoint 2.29 and exercises 175-179

- Projection: section 2.3, checkpoint 2.27 and exercises 167-172

- Arc Length: section 3.3: checkpoint 3.9, exercises 102-112

Prep.Day6

Task 6.1

We can generalize what we've done to find the work done by any force (doesn't have to be constant), acting on any object, along any path. Recall that work is a transfer of energy. Consider the following examples:

- A tornado picks up a couch and applies forces to the couch as it swirls around the center. Work is the transfer of the energy from the tornado to the couch, giving the couch its kinetic energy.

- When an object falls, gravity does work on the object. The work done by gravity converts potential energy to kinetic energy.

- If we consider the flow of water down a river, it is gravity that gives the water its kinetic energy. We can place a hydroelectric dam next to a river to capture a lot of this kinetic energy. Work transfers the kinetic energy of the river to rotational energy of the turbine, which eventually ends up as electrical energy available in our homes.

When we study work, we are really studying how energy is transferred. This is one of the key components of modern life. Recall that the work done by a vector field $\vec F$ through a displacement $\vec d$ is the dot product $\vec F\cdot \vec d$.

- When object moves from $A=(6,0)$ to $B=(0,3)$ encountering the constant force $\vec F = (2,5)$, the work is done by $\vec F$ as the object moves from $A$ to $B$ is simply the displacement $B-A=(-6,3)$ dotted by the force, so we have $W = \vec F\cdot \vec d = (2,5)\cdot(-6,3) = -12+15=3$.

An object moves from $A=(6,0)$ to $B=(0,4)$. A parametrization of the object's path is $\vec r(t) = (-3,2)t+(6,0)$ for $0\leq t\leq 2$.

- For $0\leq t\leq 1$, the force encountered is $\vec F = (2,5)$. For $1\leq t\leq 2$, the force encountered is $(2,7)$. How much work is done in the first second? How much work is done in the last second? How much total work is done?

- If we encounter a constant force $\vec F$ over a little displacement $d\vec r$, explain why the little work done is $\ds dW = \vec F\cdot d\vec r =\vec F\cdot \frac{d\vec r}{dt}dt $.

- Suppose that the force constantly changes as we move along the curve. At $t$, we encountered the force $\vec F(t) = (2,5+2t)$, which we could think of as the wind blowing stronger and stronger to the north. Explain why the total work done by this force along the path is $$\ds W=\int \vec F\cdot d\vec r = \int_0^2 (2,5+2t)\cdot (-3,2)dt.$$ Then compute this integral and show you get 16.

- If you are familiar with the units of energy, complete the following. What are the units of $\vec F$, $d\vec r$, and $dW$.

If a force of magnitude $F$ acts through a displacement with magnitude $d$, then the most basic definition of work is $W=Fd$, the product of the force and the displacement. Recall that this basic definition has a few assumptions.

- The force $F$ must act in the same direction as the displacement.

- The force $F$ must be constant throughout the displacement.

- The displacement must be in a straight line.

The dot product let's us remove the first assumption as work is $W=\vec F\cdot \vec r,$ where $\vec F$ is a force acting through a displacement $\vec r$. We just saw we can remove the assumption that $\vec F$ is constant to obtain $$W=\int \vec F \cdot d\vec r = \int_a^b F\cdot \frac{d\vec r}{dt}dt, $$ provided we have a parametrization of $\vec r$ with $a\leq t\leq b$. We now get rid of the assumption that $\vec r$ is a straight line.

- Suppose that we move along the circle $C$ parametrized by $\vec r(t) = (3\cos t,3\sin t)$. As we move along $C$, we encounter a rotational force $\vec F(x,y) = (-2y,2x)$.

- Draw $C$. Then at several points on the curve, draw the vector field $\vec F(x,y)$. For example, at the point $(3,0)$ you should have the vector $\vec F(3,0)=(-2(0),2(3))=(0,6)$, a vector sticking straight up 6 units. Are we moving with the vector field, or against the vector field?

- Explain why we can state that a little bit of work done by a force $\vec F$ over a small displacement $d\vec r$ is $dW = \vec F\cdot d\vec r$. Why does it not matter that $\vec r$ does not move in a straight line?

- Since a little work done by $\vec F$ along $d\vec r$ (a small bit of $C$) is $dW = \vec F\cdot d\vec r$, we know that the total work done is $\int dW = \int \vec F\cdot d\vec r$. This gives us $$W = \int_C\left(-2y,2x\right)\cdot d\vec r = \int_0^{2\pi}\left(-2(3\sin t),2(3\cos t)\right)\cdot(-3\sin t, 3\cos t)dt.$$ Complete the integral, showing that the work done by $\vec F$ along $C$ is $36\pi$.

$$W = \int_C \vec F\cdot d\vec r= \int_a^b \vec F(\vec r(t))\cdot \frac{d\vec r}{dt}dt.$$ Note that we put the $C$ under the integral $\int_C$ to remind us that we are integrating along the curve $C$. This means we need to get a parametrization of the curve $C$, and give bounds before we can integrate with respect to $t$.

If we let $\vec F = (M,N)$ and we let $\vec r(t)=(x,y)$, so that $d\vec r = (dx,dy)$, then we can write work in the differential form $$W = \int_C \vec F\cdot d\vec r= \int_C (M,N)\cdot (dx,dy) = \int_C Mdx+Ndy.$$

Task 6.2

Suppose an object travels along the path given by $\vec r(t) = (3t,-2t^2)$. The velocity is $\vec v(t) = (3,-4t)$ and the acceleration is $\vec a(t)=(0,-4)$.

- Is there a time $t$ at which the velocity and acceleration vectors are parallel? Explain.

- Compute the vector component of the acceleration vector that is parallel to the velocity vector. In other words, compute $\text{proj}_{\vec v}\vec a$. We'll call this vector $\vec a_{\parallel \vec v}$.

- What is the vector component of the acceleration vector that is orthogonal to the velocity vector? We'll call this vector $\vec a_{\perp \vec v}$.

- Draw a picture that shows the relationship among $\vec v$, $\vec a$, $\vec a_{\parallel \vec v}$, and $\vec a_{\perp \vec v}$.

Task 6.3

As the semester goes, we'll be learning to use Mathematica. You can install Mathematica for free as BYU-I student (see here to obtain Mathematica if you do not already have it). If you've never used Mathematica before, no worries. Here is Fast Introduction to Mathematica for Math Students. After reading the "Entering Input" section, feel free to click on the tabs on the left for more information about any topic needed.

- Let's write a block of code in Mathematica to compute the arc length of any parameterized curve.

- First, define a vector function in Mathematica to represent the parameterized curve $\ds \vec r(t) = \left(t^3,\frac{3t^2}{2}\right)$. Something like r = {t^3,3t^2/2}.

- Define some variables to hold the upper and lower limits for the parameter $t$ (something like a=1 and b=3).

- Add a line to your block of code that uses ParametricPlot[] to create a graph of the function. This verifies that the function is defined correctly.

- Compute the derivative or $\vec r$ using the derivative command ( D[]).

- Compute the length of the derivative using the Norm[] command.

- Compute the arc length of the curve using the Integrate[] command. You can use the N[] command to get a decimal approximation.

- Try putting all of the commands above into a single block of code, so that you can run it all with one execution.

- Copy the block of code that you created, then change the interval of integration to $2\leq t\leq 5$, and see if the plot as well as arc length update.

- Let's now use the work above to examine arc length for a few other curves. For each curve below, set up an integral formula which would give the length. Then sketch the curve. Try using them in the program you wrote above. Do not worry about integrating them by hand (they will get ugly really fast, and some are impossible).

- The parabola $\vec r(t) = (t,t^2)$ for $t\in[0,3]$.

- The ellipse $\vec r(t) = (4\cos t,5\sin t)$ for $t\in[0,2\pi]$.

- The hyperbola $\vec r(t) = (\tan t,\sec t)$ for $t\in[-\pi/ 4,\pi/4]$.

Task 6.4

The last problem for prep each day will point to relevant problems from OpenStax. Spend 30 minutes working on problems from the sections below.

- Work on paths (line integrals): section 2.3, checkpoint 6.18, example 6.23 and exercises 49-54

- Return to any of the previous day's OpenStax problems to locate extra practice.

Prep.Day7

Task 7.1

Consider the parametric curve $\vec r(t) = (t^2-3t, 4t-5)$ for $0\leq t\leq 3$.

- Draw the curve.

- Compute the velocity and speed at any time $t$.

- Give an equation of tangent line at $t=2$.

- Compute the acceleration at $t=2$.

- At $t=2$, compute the vector component of the acceleration that is parallel to the velocity, and the vector component of the acceleration that is orthogonal to the velocity.

- Set up an integral to compute the arc length of the curve. Then compute the integral (using software is fine).

Task 7.2

Consider the parabolic curve $y=4-x^2$ for $-1\leq x\leq 2$, and the vector field $\vec F(x,y) = (2x+y,-x)$. A parametrization $\vec r(t)$ of this parabolic curve that starts at $(-1,3)$ and ends at $(2,0)$ is $\vec r(t) = (t, 4-t^2)$.

- Compute $d\vec r$ and state $dx$ and $dy$. What are $M$ and $N$ in terms of $t$?

- Compute the work done by $\vec F$ on an object that moves along the parabola from $(-1,3)$ to $(2,0)$ (i.e. compute $\int _C Mdx+Ndy$). Check your work using the Sage code at the end of this problem.

- How much work is done by $\vec F$ to move an object along the same parabola from $(2,0)$ to $(-1,3)$. In other words, if you traverse along a path backwards, how much work is done?

- We now want to know how much work is done by the same vector field on an object that moves along a straight line from $(-1,3)$ to $(2,0)$.

- Give a parametrization $\vec r(t)$ of the straight line curve that starts at $(-1,3)$ and ends at $(2,0)$. Make sure you give bounds for $t$.

- Compute $d\vec r$ and state $dx$ and $dy$. What are $M$ and $N$ in terms of $t$?

- Compute the work done by $\vec F$ to move an object along the straight line path from $(-1,3)$ to $(2,0)$. Again, check your work using the Sage code at the end of this problem. Note that you must type the times symbol in (3*t-1, ...), otherwise, you'll get an error.

- Optional (we'll discuss this in class if you don't have it). How much work does it take to go along the closed path that starts at $(2,0)$, follows the parabola $y=4-x^2$ to $(-1,3)$, and then returns to $(2,0)$ along a straight line. Show that this total work is $W=-9$.

Use SageMath to check your work above. Click to see the Sage code.

Hit evaluate at the bottom. Feel free to modify the code below to fit your needs.

var('t','x','y') #Define your variables

r(t) = (t,4-t^2) #State your parametrization

bounds = (t,-1,2) #Give bounds for the parametrization

F(x,y) = (2*x+y,-x) #State the vector field

xbounds = (x,-1,2) #These bounds are useful if you want to make a good plot.

ybounds = (y,0,4) #These bounds are useful if you want to make a good plot.

dr = r.diff(t) #Compute the derivative

dW=F(*r(t)).dot_product(dr(t)) #Find a little bit of work. The code r[0] gives the first component, and r[1] gives the second.

W=integrate(dW,bounds)

pretty_print(html("""The work done by $F=%s$ along the curve r=$%s$

over the bounds $%s$ is $%s$"""%tuple(map(latex, [F(x,y), r(t), bounds, W]))))

show(table([

[r"$\vec r(t)$", "$(x,y)$", r(t)],

[r"$d\vec r$", "$(dx,dy)$", dr(t)],

["$\vec F(x,y)$", F(x,y), F(*r(t))],

["$M$", F(x,y)[0], F(*r(t))[0]],

["$N$", F(x,y)[1], F(*r(t))[1]],

[r"$dW=\vec F\cdot d\vec r$", "$Mdx+Ndy$", dW],

[r"$W=\int_C \vec F\cdot d\vec r$",W,W]

]

))

p=parametric_plot(r(t),bounds)

p+=plot_vector_field(F,xbounds,ybounds)

show(p)

Task 7.3

Density is generally a mass per unit volume. However, when talking about a wire, it's simpler to let density be the mass per unit length. We can make objects out of composite materials, where the density is different at different places in the object. For example, we might have a straight wire where one end is copper and the other end is gold. In the middle, the wire slowly transitions from being all copper to all gold. Such composite materials are engineered all the time (though probably not our example wire). The density at point $(x,y,z)$ is given by the quantity $\delta (x,y,z)$.

- Suppose a wire $C$ has the parameterization $\vec r(t)$ for $t\in[a,b]$. Suppose the wire's density (mass per unit length) at a point $(x,y,z)$ on the wire is given by the function $\delta(x,y,z)$. Since density is a mass per length, multiplying density by a small length $ds$ gives us the mass of a small portion of the curve. We represent this symbolically using $dm=\delta(\vec r(t_0)) ds$. Explain why the mass $m$ of the wire is given by the formulas below (explain why each equal sign is true): $$m=\int_C dm = \int_C \delta ds = \int_a^b \delta(\vec r(t)) \left|\frac{d\vec r}{dt}\right|dt.$$

- Now suppose a wire lies along the straight segment from $(0,2,0)$ to $(1,1,3)$. A parametrization of this line is $\vec r(t) = (t,-t+2,3t)$ for $t\in[0,1]$. The wire's density (mass per unit length) at a point $(x,y,z)$ is $\delta(x,y,z)=x+y+z$.

- Is the wire heavier at $(0,2,0)$ or at $(1,1,3)$?

- What is the total mass of the wire? [Replace $x$, $y$, $z$, and $ds$ with what they equal in terms of $t$ and then integrate.]

- Now consider an insulated wire that lies along the curve $\vec r(t) = (7\cos t, 7\sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq \pi$. The wire contains charged particles where the charge per unit length at location $(x,y)$ is given by $q(x,y)=y$. We'll compute the total charge on the wire.

- Draw the curve. Then at several points on the curve write the value of $q(x,y)$ at that point. (Optional: Should the total charge be positive or negative?)

- Why is the little charge $dQ$ over a little distance $ds$ approximately given by $dQ = q(x,y)ds$?

- The total charge is the sum of the charges over all the little pieces on the rod. This gives us the total charge as $$Q_{\text{total}}=\int_CdQ=\int_C q(x,y)ds = \int_a^b y \sqrt{\left(\frac{dx}{dt}\right)^2+\left(\frac{dy}{dt}\right)^2}dt.$$ Replace $x$ and $y$ with what they are in terms of $t$ and then finish by computing the integral above.

Task 7.4

The last problem for prep each day will point to relevant problems from OpenStax. Spend 30 minutes working on problems from the sections below.

- Return to any of the previous day's OpenStax problems to locate extra practice.

Prep.Day8

Learning Target Checkoff

The first learning target quiz will appear in I-Learn. Complete and submit the quiz before the due date.

Prep.Day9

Task 9.1

We have shown that for a parametric curve given by $\vec r(t)$, for $a\leq t\leq b$, the length of the curve is given by $s = \int_a^b \left|\dfrac{d \vec r}{dt}\right|dt$. We can use a different variable for the parameter, say $\tau$, and then for the curve $\vec r(\tau )$, for $0\leq \tau \leq t$ we get the arc length parameter $$s(t) = \int_0^t \left|\dfrac{d \vec r}{d\tau}\right|d\tau.$$ This provides a function $s(t)$ that tells us the arc length traveled along a curve after $t$ units of time. Note that the derivative of $s(t)$ is (why?) $$\frac{ds}{dt} = \frac{d}{dt}\int_0^t \left|\dfrac{d \vec r}{d\tau}\right|d\tau = \left|\dfrac{d \vec r}{dt}\right|,$$ which is just the speed. By requiring that speed be positive on a curve, then the arc length parameter is an increasing function. This is the reason that the definition of a smooth curve requires that the a parametrization have a nonzero derivative.

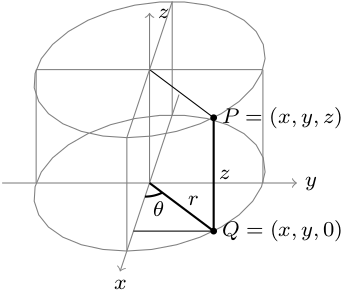

- For the helix $\vec r(t) = (3\cos t, 3\sin t, 4t)$, set up the intergral formula that gives the arc length parameter, and then simplify to show that the arc length parameter is $s(t) = 5t$.

- If you've traveled 20 units along the helix $\vec r(t) = (3\cos t, 3\sin t, 4t)$, how much time has elapsed? In general, if you've traveled $s$ units, how much time has elapsed. You will have written $t$ as a function of the arc length $s$, obtaining the inverse function $t(s)$.

- State the functions $\vec r(t)$ and $\vec r(t(s))$. Then compute both $\dfrac{d\vec r}{dt} = \dfrac{d\vec r(t)}{dt}$ and $\dfrac{d\vec r}{ds}=\dfrac{d\vec r(t(s))}{ds}$.

- Rather than writing $\dfrac{d\vec r}{ds}$ in terms of $s$, it's common to replace $s$ with $s(t)$, giving $\dfrac{d\vec r}{ds}(t)$. Explain why, in general, we have $\dfrac{d\vec r}{ds}(t) = \dfrac{d\vec r/dt}{ds/dt}$.

- For the curve $\vec r(t) = (a\cos t, a\sin t, bt)$, compute both $\dfrac{d\vec r}{dt}$ and $\dfrac{d\vec r}{ds}$.

- Show that the magnitude of $\dfrac{d\vec r}{ds}$ is always 1. We call this the unit tangent vector and write $\vec T = \dfrac{d\vec r}{ds}.$

Task 9.2

In this task, we'll show that the product rule applies to the dot product, and then use that to prove that if a vector-valued function has constant length, then the derivative of the function is orthogonal to the original function.

- Let $\vec r_1(t) = (f(t), g(t))$ and $\vec r_2(t) = (m(t), n(t))$. Prove that $$\frac{d}{dt}(\vec r_1\cdot \vec r_2) = \frac{d}{dt}(\vec r_1)\cdot \vec r_2+\vec r_1\cdot \frac{d}{dt}(\vec r_2).$$

- Now suppose that $\vec r(t)$ has constant length (meaning $|\vec r(t)|=c$ for some constant $c$). Prove that $\vec r(t) \cdot \dfrac{d\vec r(t)}{dt} = 0$. [Hint, if we know $|\vec r(t)|=c$, what does this mean about $\vec r(t)\cdot \vec r(t)$? How are the dot product and length connected?]

- Draw the curve $\vec r(t) = (4\cos t+2, 4\sin t-1)$. Show that the velocity has constant length and then verify that the derivative of the velocity (so acceleration) is orthogonal to the velocity.

The problem above gets used quite often in engineering applications. If a beam is attached to a system at a single point, then the beam can rotate about the point. Because the length of the beam is constant, then any rotational forces caused by the beam as it impacts other objects will always be normal to the beam.

Task 9.3

Let $\vec u = (a,b,c)$ and $\vec v = (d,e,f)$. Our goal is to find a single nonzero vector $(x,y,z)$ that is orthogonal to both $\vec u$ and $\vec v$, preferably with as few fractions as possible in the final answer.

- Explain why we need to solve the system of equations $$ax+by+cz=0\quad\text{and}\quad dx+ey+fz=0.$$

- To solve the system above, multiply the first equation by $d$ and the second equation by $-a$ (assume for a moment that both $a$ and $d$ are not zero). Then add the two equations together to eliminate $x$, which will allow you to solve for $y$ in terms of $z$. Finish by solving for $x$ in terms of $z$ (there are many ways to do this). You will have shown that every solution to this system can be written in the form $$(x,y,z) = \left(\left(\frac{bf-ce}{ae-bd}\right)z,\left(\frac{cd-af}{ae-bd}\right)z,z\right). $$

- The above solution has some complicated fractions. Why is $(x,y,z) = (bf-ce, cd-af, ae-bd)$ a solution to the system?

From your work above you will have developed a formula for the cross product of two vectors. The cross product of the two vectors $\vec u = (u_1,u_2,u_3)$ and $\vec v = (v_1,v_2,v_3)$ is the vector $$\vec u\times \vec v = (u_2v_3-u_3v_2, u_3v_1-u_1v_3, u_1v_2-u_2v_1).$$

- Let $\vec u=(1,-2,3)$ and $\vec v=(2,0,-1)$.

- Compute $\vec u\times \vec v$ and $\vec v\times \vec u$. How are they related?

- Compute and simplify both $\vec u \cdot (\vec u\times \vec v)$ and $\vec v \cdot (\vec u\times \vec v)$. Did you get zero for both? What fact about the cross product guarantees you get zero?

Task 9.4

The last problem for prep each day will point to relevant problems from OpenStax. Spend 30 minutes working on problems from the sections below.

- Arc Length Parameter: section 3.3: checkpoint 3.10, exercises 127-128, 116, 119, 121, 126

- Look at theorem 3.3 in section 3.2. Properties 4 and 7 were task 9.2. Prove any of the other properties that seem interesting to you.

- Cross product: section 2.4: checkpoint 2.30, exercises 183-192

Prep.Day10

Task 10.1

Given a curve with parametrization $\vec r(t)$, we have already seen that a unit tangent vector is given by $\ds \vec T = \frac{d\vec r}{ds} = \frac{d\vec r/dt}{|d\vec r/dt|}$. Note that this vector has constant length of 1, which means that it's derivative, so $\frac{d\vec T}{dt}$, is orthogonal to $\vec T$. This vector describes how the direction of motion changes. The vector $\ds\vec N = \frac{d\vec T/dt}{|d\vec T/dt|}$ provides a unit vector, we call the principle unit normal vector, that describes the direction in which an object is turning. The cross product $\vec B = \vec T\times \vec N$ we call the binormal vector. These three vectors, namely $\vec T$, $\vec N$, and $\vec B$, provide what we call the Frenet or TNB frame, and are commonly used when describing motion.

- For the curve $\vec r(t) = (3\cos t, 3\sin t, 4t)$, compute $\vec T$, $\vec N$, and $\vec B$. Show how you obtained each step in your computations.

- The definitions of $\vec T$ and $\vec N$ both made them one unit long. How long is $\vec B$?

- For the curve $\vec r(t) = (t,0,t^2)$, compute $\vec T$, $\vec N$, and $\vec B$. Show how you obtained each step in your computations. If things get ugly quite quickly, because of a quotient rule, then you're on the right path.

For a visual representation of the Frenet Frame, please visit this Geogebra site. It's possible to create a very similar visual in Mathematica or Python (something you could aim for with a self-directed learning project).

Task 10.2

Given a parametric curve with parametrization $\vec r(t)$, the curvature vector is the rate of change of the direction of motion with respect to arc length, so $\ds \vec \kappa = \frac{d\vec T}{ds}$. We compute the derivative with respect to arc length so that we obtain a physical property of the curve, rather than a property that relates to how quickly we traverse the curve. The curvature is the magnitude of the curvature vectors, so $$\kappa = |\vec \kappa| = \left| \frac{d\vec T}{ds} \right|.$$ The radius of curvature is the quantity $1/\kappa$.

- Explain why $\ds \kappa = \frac{|d\vec T/dt|}{|d\vec r/dt|}$.

- For the circle $\vec r(t) = (5\cos(2t), 5\sin(2t))$, compute the curvature $\kappa$ and radius of curvature $1/\kappa$.

- For the helix $\vec r(t) = (3\cos(t), 3\sin(t),4t)$, compute the curvature and radius of curvature.

- For the parabola $\vec r(t) = (t,t^2)$, at $t=0$ compute the curvature $\kappa(0)$ and radius of curvature.

- Draw the parabola from the previous part. How would you interpret the radius of curvature at $t=0$ in this context?

Task 10.3

Let $P=(a,b,c)$ be a point on a plane in 3D. Let $\vec n=(A,B,C)$ be a normal vector to the plane (so the angle between the plane and $\vec n$ is 90$^\circ$). Let $Q=(x,y,z)$ be another point on the plane.

- What is the angle between $\vec {PQ} = (x-a,y-b,z-c)$ and $\vec n=(A,B,C)$?

- Explain why an equation of the plane through $P$ with normal vector $\vec n$ is $$A(x-a)+B(y-b)+C(z-c)=0.$$

- Consider the three points $R=(1,0,0)$, $S=(2,0,-1)$, and $T=(0,1,3)$. Give an equation of the plane which passes through these three points. [You already have a point on the plane. With three points, you can get two vectors that are in the plane. How can you get a vector that is normal to the plane?]

Task 10.4

The last problem for prep each day will point to relevant problems from OpenStax. Spend 30 minutes working on problems from the sections below.

- Return to any of the previous day's OpenStax problems to locate extra practice.

Prep.Day11

Task 11.1

We'll use Mathematica to create a program to compute all the quantities related to the TNB frame and curvature.

- Download the Mathematica file TNB-intro.nb.

- Read through the introductory examples, evaluating each block of code.

- Adapt the code to compute the TNB frame and curvature for a given curve.

Task 11.2

Recall that the curvature vector is $\kappa = \dfrac{d\vec T}{ds}$, with curvature being a the length of this vector. This vector tells us how much the direction of motion ($\vec T$) changes, as we increase the distance moved along the curve. As such, a tight corner will result in a large change of direction and hence a large curvature. Large corners will result in a small curvature.

The radius of curvature at a point, namely $1/\kappa$, provides the radius of a circle that approximates the shape of curve at that point. Large turns results in a large radius of curvature, while tight turns results in a small radius of curvature. This circle lies in the plane formed by $\vec T$ and $\vec N$ (so a normal vector to this plane is $\vec B$). We call this plane the osculating plane. The center of the circle can be found by following $\vec N$ from the point on the curve.

- For the curve $\vec r(t) = (3\cos t, 3\sin t, 4t)$, we have already computed $\vec T$, $\vec N$, $\vec B$, and $\kappa$. At $t=\pi/2$, evaluate these quantities.

- Give an equation of the the osculating plane at $t=\pi/2$. You'll need to identify a normal vector to the plane, and a point on the plane.

- Explain why the center of curvature is given by $\vec r + \frac{1}{\kappa}\vec N$.

- Give the location of the center of curvature for $\vec r(t) = (3\cos t, 3\sin t, 4t)$ at $t=\pi/2$.

Task 11.3

There are many ways to compute the TNB frame and curvature. In this problem, we'll develop a few others.

- Explain why $ \vec N = \dfrac{\vec r^{\prime\prime}_{\perp \vec r^{\prime}}}{ |\vec r^{\prime\prime}_{\perp \vec r^{\prime} }| } $.

- Explain why $ \vec B = \dfrac{\vec r^{\prime}\times \vec r^{\prime\prime}}{|\vec r^{\prime}\times \vec r^{\prime\prime}|}$.

- For a function of the form $\vec r(x) = (x, f(x))$, show that $\kappa = \dfrac{|f''(x)|}{(1+(f'(x))^2)^{3/2}}$.

Task 11.4

The last problem for prep each day will point to relevant problems from OpenStax. Spend 30 minutes working on problems from the sections below.

- section 3.3 exercises 113-151

Prep.Day12

Task 12.1

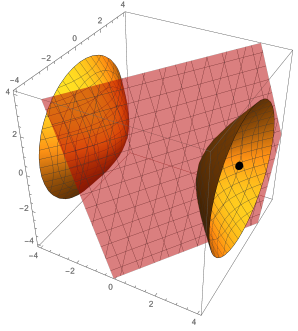

A computer chip has been disconnected from electricity and sitting in cold storage for quite some time. The chip is connected to power, and a few moments later the temperature (in Celsius) at various points $(x,y)$ on the chip is measured. From these measurements, statistics is used to create a temperature function $z=f(x,y)$ to model the temperature at any point on the chip. Suppose that this chip's temperature function is given by the equation $z=f(x,y)=9-x^2-y^2$. (This could just as easily have been the elevation of a rover at a point $(x,y)$ on a hill.) We'll be creating both a 2D contour plot (topographical map) and 3D surface plot of this function in this task.

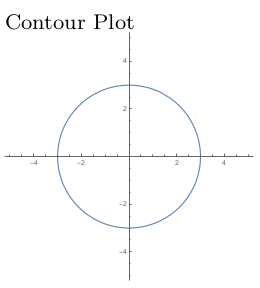

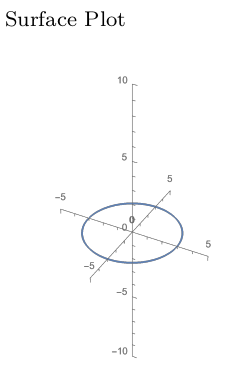

The points in the plane with temperature $f(x,y)=0$ satisfy $0=9-x^2-y^2$, or equivalently $x^2+y^2=9$. These points lie on a circle of radius 3, so we can draw that circle in the $xy$-plane (the start of our 2D contour plot) and also in 3D by plotting a circle of radius 3 at height $z=0$ (the start of our 3D surface plot). These two plots are shown below.

- What is the temperature at $(0,0)$, $(1,2)$, and $(-4,3)$?

- Which points in the plane have temperature $z=5$? Add this contour (level curve) to your 2D contour plot. Then at height $z=5$, add the same curve to the 3D surface plot.

- Repeat the above for $z=8$, $z=9$, and $z=1$. What's wrong with letting $z=10$?

- Letting $y = 0$ provides a vertical cross section of the surface. This is the curve $z = 9-x^2-0^2$. This curve cannot be drawn on the contour plot, but can be added to your 3D surface plot. Add that curve, and then add the curve given by letting $x=0$.

- Describe the 3D surface that you created with your plot. Add any extra features to your 3D surface plot to convey the 3D image you constructed. You can use the Mathematica file ContourSurfaceGradient.nb to check your work.

- For the function $f(x,y) = x^2-y$, construct a 2D contour plot and 3D surface plot.

Task 12.2

Suppose that an explosion occurs at the origin $(0,0,0)$. Heat from the explosion starts to radiate outwards. Suppose that a few moments after the explosion, the temperature at any point in space is given by $w=T(x,y,z)=100-x^2-y^2-z^2.$

- Which points in space have a temperature of 99? To answer this, replace $T(x,y,z)$ by $99$ to get $99=100-x^2-y^2-z^2$. Use algebra to simplify this to $x^2+y^2+z^2=1$. Draw this object.

- Which points in space have a temperature of 96? of 84? Draw the surfaces.

- What is the temperature at $(3,0,-4)$? Draw the set of points that have this same temperature.

- The 4 surfaces you drew above are called level surfaces. If you walk along a level surface, what happens to your temperature?

- When we compute a level surface of a function $w = f(x,y,z)$, which variable do we make constant? When we compute a level curve of a function $z=f(x,y)$, which variable do we make constant?

- Consider now the function $w=f(x,y,z)=x^2+z^2$. This function has an input $y$, but notice that changing the input $y$ does not change the output of the function.

- Draw a graph of the level surface $w=4$. [When $y=0$ you can draw one curve. When $y=1$, you draw the same curve. When $y=2$, again you draw the same curve. This kind of graph we call a cylinder, and is important in manufacturing where you extrude an object through a hole.]

- Graph the level surface $9=x^2+z^2$ (so $w=9$), and $w=16$.

You can use the Mathematica file ContourSurfaceGradient.nb to check your work.

Task 12.3

Suppose the elevation $z$ of terrain near a rover is given by the formula $z=f(x,y) = x^2+3xy$.

- Suppose that $x$ and $y$ are both functions of $t$, and then use implicit differentiation to compute $\dfrac{dz}{dt}$. Write your answer in the form $$\frac{dz}{dt} = (?)\frac{dx}{dt}+(?)\frac{dy}{dt}.$$

- The differential of $z$ (or differential of $f$ as $z=f(x,y)$) is obtained by multiplying both sides above by $dt$. Verify that $dz = (2x+3y)dx+3xdy$.

- Write the differential of $f$ as the dot product $$df = (?,?)\cdot(dx,dy).$$

When we write the differential of a function $f(x,y)$ in the form $df = M dx +N dy$, we call $M$ the partial derivative of $f$ with respect to $x$, written $f_x$ or $\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}$ or $D_x f$, and we call $N$ the partial derivative of $f$ with respect to $y$, written $f_y$ or $\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}$ or $D_y f$. The vector $(f_x,f_y)$ we call the gradient of $f$, written as $\vec\nabla f$, which means the differential of $f$ is always $$df = \vec \nabla f \cdot (dx,dy) = (f_x, f_y)\cdot (dx,dy) = f_xdx+f_ydy.$$ Similar definitions hold for functions of more variables.

- For the function $f(x,y)=3x^2+2xy$, compute the differential $df$ (in terms of $x$, $y$, $dx$, $dy$), the partial derivatives $f_x$ and $f_y$, and the gradient $\vec \nabla f(x,y)$.

- For the function $g(r,s,t)=r^2s^3+4rt^2$ compute the differential $dg$ (in terms of $r$, $s$, $t$, $dr$, $ds$, $dt$), the partial derivatives $g_r$ and $\frac{\partial g}{\partial s}$ and $D_tg$, and the gradient $\vec \nabla g(r,s,t)$.

Task 12.4

The last problem for prep each day will point to relevant problems from OpenStax. Spend 30 minutes working on problems from the sections below.

- section 4.1 exercises 14-29, 30-32, 39-41, 42-47, 48-52, 53-58

Prep.Day13

Task 13.1

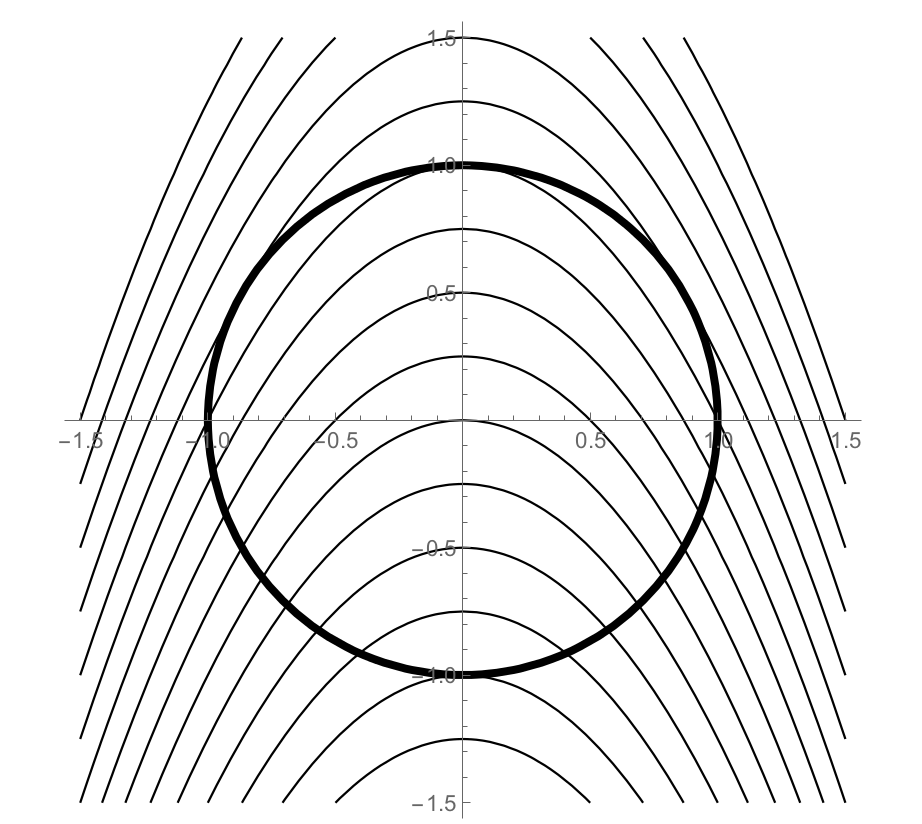

For the function $f(x,y) = 9-x^2-y^2$, we can compute the differential $df = -2xdx-2ydy$, the partial derivatives $f_x = -2x$ and $f_y=-2y$, along with the gradient $\vec \nabla f(x,y) = (-2x,-2y)$. Notice that the gradient is a vector field, so at the point $(x,y)$ we can draw the vector $(-2x,-2y)$.

- Construct a plot of the vector field $\vec \nabla f(x,y) = (-2x,-2y)$.

- Add to your vector field plot a contour plot of $f(x,y) = 9-x^2-y^2$ (we constructed a contour plot for the function in a previous Task).

- What relationships do you see between the vectors from the gradient plot, and the level curves from your contour plot.

For the function $f(x,y) = x^2-y$, we can compute the differential $df = 2xdx-1dy$, the partial derivatives $f_x = 2x$ and $f_y=-1$, along with the gradient $\vec \nabla f(x,y) = (2x,-1)$. Again, notice that the gradient is a vector field, so at the point $(x,y)$ we can draw the vector $(2x,-1)$.

- Construct a plot of the vector field $\vec \nabla f(x,y) = (2x,-1)$.

- Add to your vector field plot a contour plot of $f(x,y) = x^2-y$ (we constructed a contour plot for the function in a previous Task).

- What relationships do you see between the vectors from the gradient plot, and the level curves from your contour plot.

You can use the Mathematica file ContourSurfaceGradient.nb to check your work.

Task 13.2

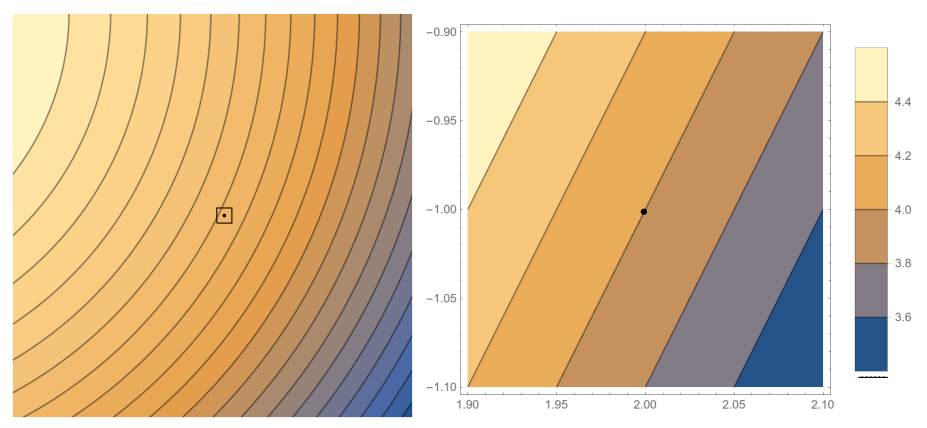

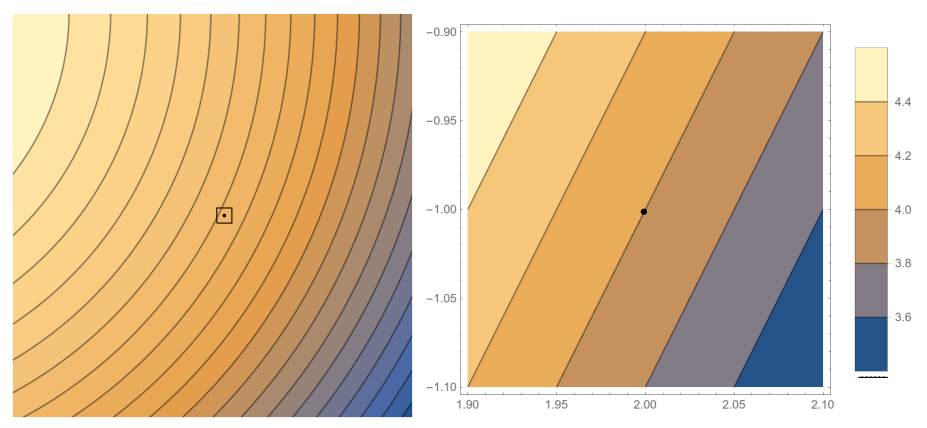

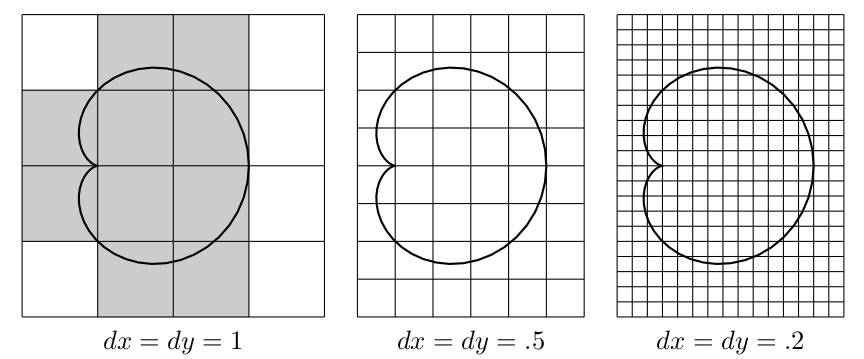

Suppose the Mars rover Curiosity is currently on a hill, and its position is at the center of the map on the left below. Zooming in on the rover's position yields the map on the right below (the color legend applies to the graph on the right).

The contours in the graph to the right each represent a change in height of 0.2 units. The bounds for the graph are $1.9\leq x\leq 2.1$ and $-1.1\leq y\leq -0.9$. For simplicity of computations, let's assume the $x$, $y$ and $z$ axes use the same units. The rover is currently located at the point $(2,-1)$, shown as a dot.

The rover can head in many directions. In this problem we'll estimate the slope in several directions. For example, if the rover follows the vector $(0,1)$, heads north, then it has to move a distance (run) of $\Delta y = 0.1$ units to hit the next contour, resulting in a change in height of $\Delta z = +0.2$ units. This means the slope in the $(0,1)$ direction is $$\ds\frac{\text{rise}}{\text{run}} = \frac{\Delta z}{\text{distance moved in $xy$ plane}} = \frac{+0.2}{0.1} = 2.$$

- Estimate the slope if the rover heads east, following $(1,0)$.

- If the rover heads south, following $(0,-1)$, estimate the slope.

- If the rover follows the direction $(1,1)$ (so northeast), what distance must the rover travel to hit the next contour? Use this to estimate the slope in the $(1,1)$ direction.

- Estimate the slope in the $(1,2)$ direction.

Rather than starting with a contour plot and using it to visually estimate slopes, let's start with a function of the form $z=f(x,y)$ and use it to compute slopes. Suppose the elevation $z$ of terrain near the rover is given by the formula $z=f(x,y) = x^2+3xy$, and the rover is currently at $P=(2,-1)$.

- Compute the differential $dz$ and write it in the form $dz = (?)dx+(?)dy$. Then evaluate $dz$ at the rover's location $P=(2,-1)$. [Check: Did you get $dz = (1)dx+(6)dy$?]

- If the rover follows the direction $(dx,dy)$, explain why the slope is $\frac{dz}{\sqrt{(dx)^2+(dy)^2}}$.

- Estimate the slope if the rover heads east, following $(dx,dy)=(1,0)$. Then estimate the slope if the rover heads north, following $(dx,dy)=(0,1)$. What do these values have to do with the partial derivatives of $f$?

- Estimate the slope in the $(1,1)$ direction and then the $(1,2)$ direction.

Task 13.3

The volume of a right circular cylinder is $V(r,h)= \pi r^2 h$.

- If we think of $h$ as a constant, so that $V(r)$ is only a function of $r$, then compute $\frac{dV}{dr}$.

- If instead we think of $r$ as a constant, so that $V(h)$ is only a function of $h$, then compute $\frac{dV}{dh}$.

- Compute the differential of $V(r,h)$, and then state the gradient $\vec \nabla V(r,h)$ along with the partial derivatives $\frac{\partial V}{\partial r}$ and $\frac{\partial V}{\partial h}$.

- If we know $r=3$ and $h=4$, and we know that $r$ could increase by $dr=0.1$ and $h$ could increase by about $dh=0.2$, then use differentials to estimate how much $V$ will increase.

Notice that we were able to compute the partial derivatives above, without ever needing to compute the differential first. We obtain $\frac{\partial V}{\partial r}$ by imagining that every variable other than $r$ was a constant, and then computing the regular derivative.

- The volume of a box is given by $f(x,y,z)=xyz$. Without computing the differential, compute $\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}$, $\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}$, and $\frac{\partial f}{\partial z}$.

- Now compute the differential $df$ (use implicit differentiation if needed) and verify that the partial derivatives you computed before actually show up in the differential $df$.

- If the current measurements are $x=2$, $y=3$, and $z=5$, and we know that expected tolerances are $dx=.01$, $dy=.02$, and $dz=.03$, then estimate the change in volume.

Task 13.4

The last problem for prep each day will point to relevant problems from OpenStax. Spend 30 minutes working on problems from the sections below.

- section 4.3, exercises 118-131

Prep.Day14

We'll spend today revisiting the prep for Day 13. You can jump ahead to day 15 if you want to get ahead. Click to view the Day 13 prep.

Day 13 - Prep

Task 13.1

For the function $f(x,y) = 9-x^2-y^2$, we can compute the differential $df = -2xdx-2ydy$, the partial derivatives $f_x = -2x$ and $f_y=-2y$, along with the gradient $\vec \nabla f(x,y) = (-2x,-2y)$. Notice that the gradient is a vector field, so at the point $(x,y)$ we can draw the vector $(-2x,-2y)$.

- Construct a plot of the vector field $\vec \nabla f(x,y) = (-2x,-2y)$.

- Add to your vector field plot a contour plot of $f(x,y) = 9-x^2-y^2$ (we constructed a contour plot for the function in a previous Task).

- What relationships do you see between the vectors from the gradient plot, and the level curves from your contour plot.

For the function $f(x,y) = x^2-y$, we can compute the differential $df = 2xdx-1dy$, the partial derivatives $f_x = 2x$ and $f_y=-1$, along with the gradient $\vec \nabla f(x,y) = (2x,-1)$. Again, notice that the gradient is a vector field, so at the point $(x,y)$ we can draw the vector $(2x,-1)$.

- Construct a plot of the vector field $\vec \nabla f(x,y) = (2x,-1)$.

- Add to your vector field plot a contour plot of $f(x,y) = x^2-y$ (we constructed a contour plot for the function in a previous Task).

- What relationships do you see between the vectors from the gradient plot, and the level curves from your contour plot.

You can use the Mathematica file ContourSurfaceGradient.nb to check your work.

Task 13.2

Suppose the Mars rover Curiosity is currently on a hill, and its position is at the center of the map on the left below. Zooming in on the rover's position yields the map on the right below (the color legend applies to the graph on the right).

The contours in the graph to the right each represent a change in height of 0.2 units. The bounds for the graph are $1.9\leq x\leq 2.1$ and $-1.1\leq y\leq -0.9$. For simplicity of computations, let's assume the $x$, $y$ and $z$ axes use the same units. The rover is currently located at the point $(2,-1)$, shown as a dot.

The rover can head in many directions. In this problem we'll estimate the slope in several directions. For example, if the rover follows the vector $(0,1)$, heads north, then it has to move a distance (run) of $\Delta y = 0.1$ units to hit the next contour, resulting in a change in height of $\Delta z = +0.2$ units. This means the slope in the $(0,1)$ direction is $$\ds\frac{\text{rise}}{\text{run}} = \frac{\Delta z}{\text{distance moved in $xy$ plane}} = \frac{+0.2}{0.1} = 2.$$

- Estimate the slope if the rover heads east, following $(1,0)$.

- If the rover heads south, following $(0,-1)$, estimate the slope.

- If the rover follows the direction $(1,1)$ (so northeast), what distance must the rover travel to hit the next contour? Use this to estimate the slope in the $(1,1)$ direction.

- Estimate the slope in the $(1,2)$ direction.

Rather than starting with a contour plot and using it to visually estimate slopes, let's start with a function of the form $z=f(x,y)$ and use it to compute slopes. Suppose the elevation $z$ of terrain near the rover is given by the formula $z=f(x,y) = x^2+3xy$, and the rover is currently at $P=(2,-1)$.

- Compute the differential $dz$ and write it in the form $dz = (?)dx+(?)dy$. Then evaluate $dz$ at the rover's location $P=(2,-1)$. [Check: Did you get $dz = (1)dx+(6)dy$?]

- If the rover follows the direction $(dx,dy)$, explain why the slope is $\frac{dz}{\sqrt{(dx)^2+(dy)^2}}$.

- Estimate the slope if the rover heads east, following $(dx,dy)=(1,0)$. Then estimate the slope if the rover heads north, following $(dx,dy)=(0,1)$. What do these values have to do with the partial derivatives of $f$?

- Estimate the slope in the $(1,1)$ direction and then the $(1,2)$ direction.

Task 13.3

The volume of a right circular cylinder is $V(r,h)= \pi r^2 h$.

- If we think of $h$ as a constant, so that $V(r)$ is only a function of $r$, then compute $\frac{dV}{dr}$.

- If instead we think of $r$ as a constant, so that $V(h)$ is only a function of $h$, then compute $\frac{dV}{dh}$.

- Compute the differential of $V(r,h)$, and then state the gradient $\vec \nabla V(r,h)$ along with the partial derivatives $\frac{\partial V}{\partial r}$ and $\frac{\partial V}{\partial h}$.

- If we know $r=3$ and $h=4$, and we know that $r$ could increase by $dr=0.1$ and $h$ could increase by about $dh=0.2$, then use differentials to estimate how much $V$ will increase.

Notice that we were able to compute the partial derivatives above, without ever needing to compute the differential first. We obtain $\frac{\partial V}{\partial r}$ by imagining that every variable other than $r$ was a constant, and then computing the regular derivative.

- The volume of a box is given by $f(x,y,z)=xyz$. Without computing the differential, compute $\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}$, $\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}$, and $\frac{\partial f}{\partial z}$.

- Now compute the differential $df$ (use implicit differentiation if needed) and verify that the partial derivatives you computed before actually show up in the differential $df$.

- If the current measurements are $x=2$, $y=3$, and $z=5$, and we know that expected tolerances are $dx=.01$, $dy=.02$, and $dz=.03$, then estimate the change in volume.

Task 13.4

The last problem for prep each day will point to relevant problems from OpenStax. Spend 30 minutes working on problems from the sections below.

- section 4.3, exercises 118-131

Prep.Day15

Every time we compute a differential $df = f_xdx+ f_ydy$, we're following a pattern that shows up so often that it's given a name (linear combination). At some point you may take a linear algebra course where you'll focus quite a bit on linear combinations, and quickly adopt matrices to help speed up the process of writing linear combinations.

Given $n$ vectors $\vec v_1, \vec v_2,\cdots,\vec v_n$ and $n$ scalars $c_1, c_2, \cdots, c_n$ the linear combination of these vectors using these scalars is the sum $$\sum_{i=1}^n c_1 \vec v_i = c_1\vec v_1+c_2\vec v_2+\cdots+c_n\vec v_n.$$ Matrix notation and products were invented to organize linear combinations into a visually appealing compact form. We place each vector in the column of a matrix, and then place the corresponding scalars into a single column vector after the matrix. The linear combination above, in matrix form, becomes the matrix product $$c_1\vec v_1+c_2\vec v_2+\cdots+c_n\vec v_n = \begin{bmatrix} \begin{pmatrix}\\\vec v_1\\ \ \end{pmatrix} &\begin{pmatrix}\\\vec v_2\\ \ \end{pmatrix} &\cdots &\begin{pmatrix}\\\vec v_n\\ \ \end{pmatrix} \end{bmatrix} \begin{pmatrix}c_1\\c_2\\\vdots\\c_n\end{pmatrix}.$$

The derivative (or total derivative) of a function is a matrix whose columns are the partial derivatives of the function. The partial derivatives we insert into the columns of the matrix in the same order in which the variables are listed for the function. Some examples follow.

- For the function $f(x)$, the derivative is $Df(x) = \begin{bmatrix}f_x\end{bmatrix} =\begin{bmatrix}\frac{df}{dx}\end{bmatrix}$, with differential $df = f_xdx$.

- For the function $f(x,y)$, the derivative is $Df(x,y) = \begin{bmatrix}f_x&f_y\end{bmatrix}$, with differential $df = f_xdx+f_ydy$.

- For the function $f(r,s,t)$, the derivative is $Df(r,s,t) = \begin{bmatrix}f_r&f_s&f_t\end{bmatrix}$, with differential $df = f_rdr+f_sds+f_tdt$.

- For the function $\vec r(u,v)$, the derivative is $D\vec r(u,v) = \begin{bmatrix}\vec r_u&\vec r_v\end{bmatrix}$, with differential $d\vec r = \vec r_udu+\vec r_vdv$.

Task 15.1

Let's practice using the definitions above. For each function below, (a) compute and label all relevant partial derivatives. Then (b) write the differential $df$ as a linear combination of the partial derivatives. Then (c) write $df$ as a matrix product. Finish by (d) stating the total derivative $Df$ of the function.

- $f(x,y)=x^2y$ [Clearly label all 4 things you were asked to find, namely (a) all partials, (b) $df$ as a linear combination, (c) $df$ as a matrix product, and (d) the derivative $Df$.]

- $f(x,y)=x^2+2xy+3y^2$

- $f(x,y,z)=3xz-x^2y$

Task 15.2

The gradient of a function $f(x,y)$ is itself a function. When we compute the partial derivatives of the gradient, we obtain vectors instead of numbers. This task has you examine the differential, partials, and derivative of the gradient of a function. We'll soon see that the derivative of the gradient is precisely the key to classifying maximums and minimums of a function.

The function $f(x,y) = x^2+3xy+2y^2$ has the gradient $\vec \nabla f = (2x+3y,3x+4y)$. This is the vector field $$\vec F = (2x+3y,3x+4y).$$

- Find the differential $d\vec F$ and write it as the linear combination $$d\vec F = \begin{pmatrix}?\\?\end{pmatrix}dx+\begin{pmatrix}?\\?\end{pmatrix}dy.$$

- Rewrite the above differential as a matrix product, so fill in the blanks below. $$d\vec F = \begin{pmatrix}?&?\\?&?\end{pmatrix}\begin{pmatrix}?\\?\end{pmatrix}.$$

- Clearly label the two partial derivatives $\frac{\partial \vec F}{\partial x}$ and $\vec F_y$.

- State the total derivative $D\vec F(x,y)$ (it should be a 2 by 2 matrix). [Note: We also write the derivative of the gradient as $D^2f(x,y)$, or $D\vec\nabla f(x,y)$, and call the resulting matrix the Hessian of $f$. Some people use the notation $\vec \nabla ^2 f$ for the Hessian, though this notation also gets use for the Laplacian $\vec \nabla \cdot (\vec \nabla f)$, which is a very different quantity.]

- The function $f(x,y) = xy^2$ has gradient $\vec F = (y^2, 2xy)$. Repeat the above to obtain the differential of $\vec F$ (as a linear combination, and in matrix form), the partials of $\vec F$, and the derivative $D\vec F(x,y)$.

Task 15.3

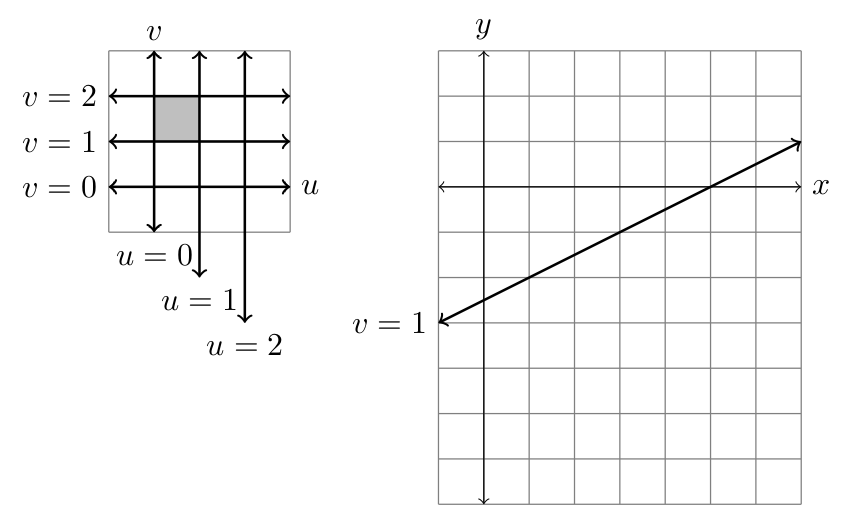

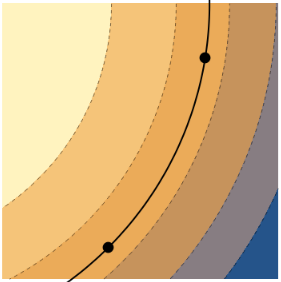

Suppose a rover moves along the level curve of a function $f(x,y)$ following the path $\vec r(t)=(x,y)$. An example of such a scenario is shown below (note that lighter colors correspond to greater outputs of $f(x,y)$. )

Label the dots $A$ and $B$ (it doesn't matter which you label $A$ or $B$). Our goal is to prove that the gradient of $f$ is normal to level curves.

- At each dot in the picture on the right, draw a vector that represents a possible option for $\ds\frac{d\vec r}{dt} = \left(\frac{dx}{dt},\frac{dy}{dt}\right)$.

- Suppose $\vec r(0)=A$ and $\vec r(1)=B$. If we know that $f(\vec r(0)) = 7$, then what is $f(\vec r(1))$? Explain.

- As the rover moves along $\vec r(t)$, how much does $f$ change? Use this to give a value for $\ds\frac{df}{dt}$?

- Explain why $\vec \nabla f$ and $\ds\frac{d\vec r}{dt}$ are orthogonal at any point along the level curve. (Hint: Add $dt$ to the denominators of the the differential $df = f_xdx+f_ydy$ , and then write the differential as a dot product. Since we are on a level curve, we know the value of $\ds\frac{df}{dt}$.)

- At point $A$, draw a vector that points in the same direction as $\vec \nabla f(A)$. Use your work above to explain why the gradient of $f$ must be normal to the level curve.

Task 15.4

The last problem for prep each day will point to relevant problems from OpenStax. Spend 30 minutes working on problems from the sections below.

- Return to any of the previous day's OpenStax problems to locate extra practice.

Prep.Day16

Learning Target Checkoff

A learning target quiz will appear in I-Learn. Complete and submit the quiz before the due date.

Prep.Day17

Task 17.1

We'll focus this task on making sure we understand how differentials can help us approximate changes in a function.

A forest ranger needs to estimate the height of a tree. The ranger stands 50 feet from the base of tree and measures the angle of elevation to the top of the tree to be about 60$^\circ$.

- If this angle of 60$^\circ$ is correct, then what is the height of the tree? Explain in general why the height of the tree is $h(\theta) = 50 \tan \theta$.

- Compute the differential $dh$ in terms of $\theta$ and $d\theta$.

- The ranger's angle measurement is mostly likely off by some amount. If the error in the ranger's measurement could be as much as $d\theta = 5^\circ$ (so $\frac{5\pi}{180}$ radians), then use differentials to estimate how large the error in the height could be (so compute $dh$). If your answer here is quite large (much larger than the height of the tree), then look back at your work and see if using radians instead of degrees makes a difference. Why does it? Feel free to ask in class.

- Compute the height if the angle were exactly 65 instead of 60. What's the actual difference between these two heights?

The US mint creates coins that are roughly a cylindrical shape, with volume $V = \pi r^2h$. Unfortunately, not every coin is exactly the same size, and small errors in $r$ (given by $dr$) and small errors in $h$ (given by $dh$), affect the amount of material needed to mint these coins.

- Compute $dV$ to give an approximate for the change in volume given by the errors $dr$ and $dh$.

- The radius of a coin is much larger than the height. Will an error in the radius, or an error in the height, cause a larger change in volume? Explain using your differentials.

- A soda can company has a cylindrical shape that instead has a large $h$ with small $r$. Will an error in the radius, or an error in the height, cause a larger change in volume in this situation.

Task 17.2

Suppose that our rover is located at point $P=(x,y)$ on a hill whose elevation is given by $z=f(x,y)$. The rover will be moving in the direction parallel to $\vec u$.

- Explain why the slope of the hill at $P$ in the direction $\vec u = (dx,dy)$ is given by $$\frac{dz}{\sqrt{(dx)^2+(dy)^2}}.$$

- Prove that this slope can be written, using gradients, as $$\vec \nabla f(P) \cdot \frac{\vec u}{|\vec u|}.$$

- Use the above fact to compute the slope of a hill given by $f(x,y) = x^2+3xy$ at $P=(2,-1)$ in the direction $\vec u = (3,4)$. (We call this the directional derivative of $f$ at $P$ in the direction $\vec u$, written $D_{\vec u}f(P)$.

The directional derivative of $f$ in the direction of the vector $\vec u$ at a point $P$ is defined to be $$D_{\vec u} f(P)=\vec \nabla f \cdot \frac{\vec u}{|\vec u|}.$$ We can simplify the above to just $f(P)=\vec \nabla f \cdot \hat u$ if $\hat u$ is a unit vector. We dot the gradient of $f$ with a unit vector in the direction of $\vec u$.

- Show that the partial derivative of $f$ with respect to $x$ is precisely the directional derivative of $f$ in the $(1,0)$ direction.

- Show that the partial derivative of $f$ with respect to $y$ is precisely the directional derivative of $f$ in the $(0,1)$ direction.

Please watch this short 2 part video that discusses the gradient a bit more, and how you can connect the gradient to the slope in various directions.

Task 17.3

Suppose our rover is located at a point $P$ on a hill whose elevation is given by $z=f(x,y)$. Recall that the directional derivative of $\vec f$ at $P$ in the direction $\vec u$ is the dot product $D_{\vec u} f(P)=\vec \nabla f(P)\cdot \frac{\vec u}{|\vec u|}.$ Also recall that we can compute dot products using the law of cosines $\vec \nabla f(P)\cdot \vec u= |\vec \nabla f(P)| |\vec u|\cos\theta,$ where $\theta$ is the angle between $\vec \nabla f(P)$ and $\vec u$.

- Give a formula for the angle $\theta$ between the two vectors $\vec \nabla f$ and $\vec u$?

- Given a direction $\vec u$, the directional derivative will give the slope of $f$ at $P$ in the direction $\vec u$. We want to know which direction we should be pick to obtain the largest slope (directional derivative). Explain why the angle between $\vec u$ and $\vec \nabla f(P)$ must be 0, in order to obtain the largest slope.

- State a vector $\vec u$ that yields the largest directional derivative.

- When $\vec u$ is parallel to $\vec \nabla f(P)$, show that $D_{\vec u}f(P) = |\vec \nabla f(P)|$. In other words, explain why the length of the gradient is precisely the slope of $f$ in the direction of greatest increase (the slope in the steepest direction).

- Which direction points in the direction of greatest decrease? What is the slope in that direction?

- In your own words, summarize what facts this task helped you learn about the gradient.

Task 17.4

The last problem for prep each day will point to relevant problems from OpenStax. Spend 30 minutes working on problems from the sections below.

- Return to any of the previous day's OpenStax problems to locate extra practice.

Prep.Day18

Task 18.1

In first semester calculus, differential notation is $dy=f' dx$. At $x=c$, the tangent line passes through the point $P=(c,f(c))$. If $Q=(x,y)$ is any other point on the line, then the vector $\vec {PQ} = (x-c,y-f(c))$ tells us that when $dx=x-c$ we have $dy=y-f(c)$. Substitution give us an equation for the tangent line tangent line as $$\underbrace{y-f(c)}_{dy}={f'(c)}\underbrace{(x-c)}_{dx}.$$ This equation tells us that a change in the output ($y-f(c)$) equals the derivative times a change in the input ($x-c$). In this task, we'll repeat this process to obtain an equation of a tangent plane to a function $f(x,y)$, where differential notation gives $$dz = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}dx+\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}dy.$$

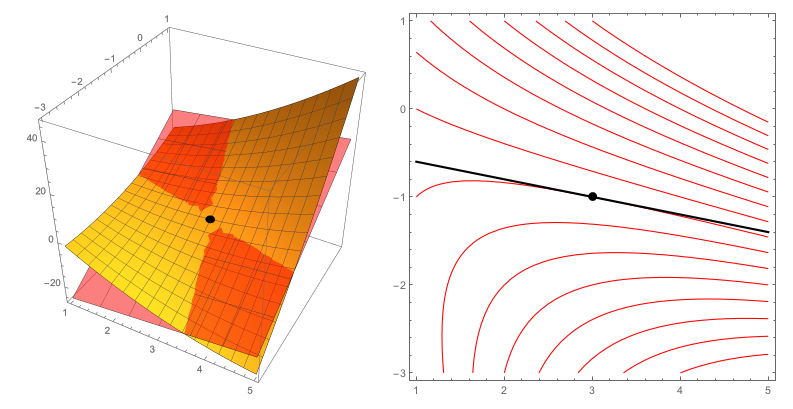

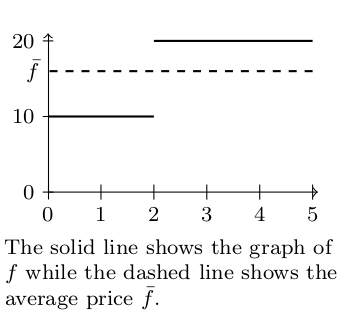

Consider the function $z=f(x,y)=9-x^2-y^2$. We'll be finding an equation of the tangent plane to $f$ at $(x,y)=(2,1)$. Here is surface plot along with the tangent plane at $(2,1,f(2,1))$, together with a contour plot.

- Compute the partial derivatives $f_x$ and $f_y$, and the differential $dz$. At the point $(x,y) = (2,1)$, evaluate the partial derivatives and the function $z=f(x,y)$.

- One point on the tangent plane to the surface at $(2,1)$ is the point $P=(2,1,f(2,1))$. Let $Q=(x,y,z)$ be another point on this plane. Use the vector $\vec{PQ}$ to obtain $dz$ when $dx = x-2$ and $dy = y-1$.

- We'd like an equation of the tangent plane to $f(x,y)$ when $x=2$ and $y=1$. Differential notation tells us that $$\underbrace{z-?}_{dz}=(-4)\underbrace{(x-?)}_{dx}+(?)\underbrace{(y-?)}_{dy}.$$ Fill in the blanks to get an equation of the tangent plane.

- Rewrite the equation you got in the form $A(x-a)+B(y-b)+C(z-c)=0$ and state a normal vector to the plane.

- The level curve of $f$ that passes through $(2,1)$ has no change in height, so $dz=0$. Use this fact to give an equation of the tangent line to this level curve at $(2,1)$.

Now let $z=f(x,y)=x^2+4xy+y^2$. At the point $P=(x,y)=(3,-1)$, we'll give an equation of the tangent plane to the surface and an equation of the tangent line to the level curve of $f$ that passes through this point.

- Give an equation of the tangent plane at $P=(x,y)=(3,-1)$. [Hint: Find $f_x$, $f_y$, $dx$, $dy$, and then $dz$, all at $(x,y)=(3,-1)$. Then substitute, as done above.]

- The level curve of $f$ that passes through $P$ is a curve in the plane. Give an equation of the tangent line to this curve at $P$. [Hint: Since we're on a level curve, what does $dz$ equal? The equation is almost identical to the previous part, with one minor change based on what $dz$ equals.]

The tangent plane and tangent line you just found are shown below.

Task 18.2

A rover moves on a hill where elevation is given by $z=f(x,y)=9-x^2-y^2$. The rover's path is parametrized by $\vec r(t)=(2\cos t, 3\sin t)$.

- At time $t=0$, what is the rover's position $\vec r(0)$, and what is the elevation $f(\vec r(0))$ at that position? Then find the positions and elevations at $t=\pi/2$, $t=\pi$, and $t=3\pi/2$ as well.

- In the plane, draw the rover's path for $t\in [0,2\pi]$. Then, on the same 2D graph, include a contour plot of the elevation function $f$. Include the level curves that pass through the points in part 1. Along each level curve drawn, state the elevation of the curve. [If you end up with an ellipse and several concentric circles, then you've done this right.]

- As the rover follows its elliptical path, the elevation is rising and falling. At which $t$ does the elevation reach a maximum? A minimum? Explain, using your graph.

- As the rover moves past the point at $t=\pi/4$, is the elevation increasing or decreasing? In other words, is $\dfrac{df}{dt}$ positive or negative? Use your graph to explain.

Notice above that we wanted $\frac{df}{dt}$, the rate of change of elevation with respect to time, even though the function $f(x,y)$ does not explicitly have $t$ as an input. The proper notation would be $\frac{d(f\circ r)}{dt}$, but this is so cumbersome that it's generally avoided. The notation $\frac{df}{dt}$ requires the reader to infer from context that $x$ and $y$ depend on $t$.

- At the point $\vec r(t)$, we'd like a formula for the elevation $f(\vec r(t))$. What is the elevation of the rover at any time $t$? [In $f(x,y)$, replace $x$ and $y$ with what they are in terms of $t$.]

- Compute $df/dt$ (the derivative as you did in first-semester calculus).

Let's repeat the above, but first compute differentials before substitution. For reference, we let $f(x,y)=9-x^2-y^2$ and $(x,y)=\vec r(t)=(2\cos t, 3\sin t)$.

- Compute the differential $df$ in terms of $x$, $y$, $dx$, and $dy$.

- Compute $dx$ and $dy$ in terms of $t$ and $dt$.

- Use substitution to write $df$ in terms of $t$ and $dt$. Then divide by $dt$ to obtain $\frac{df}{dt}$. Did you get the same answer as the previous part?

- Use your work above to state both $\vec\nabla f(x,y)$ and $\frac{d\vec r}{dt}$. Show that $\frac{df}{dt} = \vec\nabla f(x,y)\cdot \frac{d\vec r}{dt}$.

Task 18.3

A second-order partial derivative of $f$ is a partial derivative of one of the partial derivatives of $f$. The second-order partial of $f$ with respect to $x$ and then $y$ is the quantity $\frac{\partial}{\partial y}\left[\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\right]$, so we first compute the partial of $f$ with respect to $x$, and then compute the partial of the result with respect to $y$. Alternate notations exist, for example the same second-order partial above we can write as $$\frac{\partial}{\partial y}\left[\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\right]=\left(f_{x}\right)_y=f_{xy}=\ds\frac{\partial}{\partial y}\frac{\partial}{\partial x}f = \frac{\partial}{\partial y}\frac{\partial f}{\partial x} = \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial y \partial x}.$$ The subscript notation $f_{xy}$ is easiest to write. Sometimes we'll use subscript notation to mean something other than a partial derivative (like the $x$ or $y$ component of a vector), at which point we use the fractional partial derivative notation to avoid confusion.

Consider the functions $f(x,y,z) = xy^2z^3$ and $g(x,y)=x\cos(xy)$.

- First compute $\vec \nabla f$. Then compute $f_{xy}$ and $\frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial z\partial y}$. Explain how you got these. End by computing the entire second derivative $D\vec\nabla f(x,y,z)$ (it is a 3 by 3 matrix with all 9 second partials placed inside).

- Compute $g_x$ and then $g_{xy}$. Then compute $g_y$ followed by $g_{yx}$.

- Now let $f(x,y)=3xy^3+e^{x}.$ Compute the four second partials $$\ds \frac{\partial^2 f}{ \partial x^2},\quad \ds\frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial y \partial x},\quad \ds\frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial y^2}, \quad \text{ and }\ds\frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x \partial y}.$$

- For $f(x,y)=x^2\sin(y)+y^3$, compute both $f_{xy}$ and $f_{yx}$.

- Make a conjecture about a relationship between $f_{xy}$ and $f_{yx}$. Then use your conjecture to quickly compute $f_{xy}$ if $$f(x,y)=3xy^2+\tan^{2}(\cos(x)) (x^{49}+x)^{1000}.$$

Task 18.4

The last problem for prep each day will point to relevant problems from OpenStax. Spend 30 minutes working on problems from the sections below.

- Return to any of the previous day's OpenStax problems to locate extra practice.

Prep.Day19

Task 19.1

In the first calculus books, there was no mention of the chain rule. This is because differentials were extremely common notation, and the chain rule, when working with differentials, is simply substitution. In this task, we'll develop some rules for how to compute derivatives when functions depend on other functions (so composite functions).

- Suppose that $f(x,y,z) = ax+by+cz$, and $x=mt$, $y=nt$, and $z = pt$, for some constants $a,b,c,m,n,p$. Compute the differentials $df$, $dx$, $dy$, and $dz$. Then use substitution to obtain the differential of $f$ in terms of $t$ and $dt$. Finish by stating $\frac{df}{dt}$.

- Suppose now that $g$ is a function of $x$ and $y$, but $x$ and $y$ are functions of $u$, $v$, and $w$. This means, by definition of the differential and partial derivatives, that $dg = g_xdx+g_ydy$, along with $dx = x_udu+x_vdv+x_wdw$ and $dy = y_udu+y_vdv+y_wdw$. Substitution gives $$\begin{align*} dg &= g_xdx+g_ydy\\ &= g_x(x_udu+x_vdv+x_wdw)+g_y(y_udu+y_vdv+y_wdw)\\ &= (?)du+(?)dv+ (?)dw. \end{align*}$$ Fill in the question marks above, and then use your answer to state the three partials $\dfrac{\partial g}{\partial u}$, $g_v$, and $D_w g$.

- Consider the function $h(x,y,z)$, where $x$, $y$, and $z$ are functions of $r$ and $\theta$. State the differentials of $h$, $x$, $y$, and $z$, and then use substitution to prove that $$\dfrac{\partial h}{\partial r} = \dfrac{\partial h}{\partial x}\dfrac{\partial x}{\partial r} +\dfrac{\partial h}{\partial y}\dfrac{\partial y}{\partial r} +\dfrac{\partial h}{\partial z}\dfrac{\partial z}{\partial r}.$$ Obtain a similar formula for $\dfrac{\partial h}{\partial \theta}$.

Feel free to ask me in class how this relates to matrix multiplication.

Task 19.2

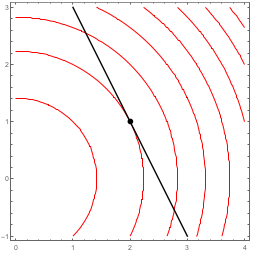

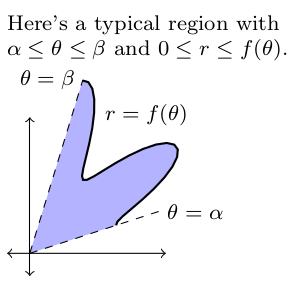

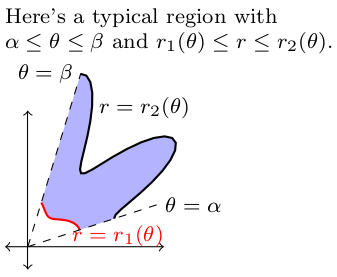

Suppose a rover travels around the circle $g(x,y)=x^2+y^2=1$. The elevation of the surrounding terrain is $f(x,y) = x^2+y+4$. The plot below shows the rover's path (the constraint $g(x,y)=1$), placed on the same grid as a contour plot of the elevation (the function $f(x,y)$ we wish to optimize).

Each level curve above represents a difference in elevation of 0.25 m. Our goal is to find the maximum and minimum elevation reached by the rover as it travels around the circle. We will optimize $f(x,y)$ subject to the constraint $g(x,y)=1$.

- Label each level curve with its elevation. Print this page, or copy the curves down on your paper.

- At which $(x,y)$ point does the rover encounter the minimum elevation? What is the minimum elevation? Explain, using the plot.

- Suppose the rover is currently at the point $(0,1)$ on its circular path. As the rover moves left, will the elevation rise or fall? What if the rover moves right? Is $(0,1)$ the location of a local maximum or local minimum?