Task 35.1

Given a change-of-coordinates $x = x(u,v)$ and $y=y(u,v)$, the differential is $$\begin{pmatrix}dx\\dy\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \frac{\partial x}{\partial u}\\ \frac{\partial y}{\partial u}\end{pmatrix}du+\begin{pmatrix}\frac{\partial x}{\partial v}\\\frac{\partial y}{\partial v}\end{pmatrix}dv = \begin{bmatrix}\frac{\partial x}{\partial u}&\frac{\partial x}{\partial v}\\\frac{\partial y}{\partial u}&\frac{\partial y}{\partial v}\end{bmatrix}\begin{pmatrix}du\\dv\end{pmatrix}.$$ The Jacobian of the change-of-coordinates, written $\dfrac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)}$, is the area of the parallelogram formed by the partial derivatives $\dfrac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial u}=\begin{pmatrix} \frac{\partial x}{\partial u}\\ \frac{\partial y}{\partial u}\end{pmatrix}$ and $\dfrac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial v}=\begin{pmatrix} \frac{\partial x}{\partial v}\\ \frac{\partial y}{\partial v}\end{pmatrix}$. The Jacobian, in 2D, is an area stretch factor that relates the area $A_{uv}$ of a small region in the $uv$-plane to the transformed region of area $A_{xy}$ in the $xy$-plane, which we often summarize with the notation $dA = \frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)}dudv.$ In terms of integrals, this gives $$\iint_R f dxdy =\iint_R f dA = \iint_R f \frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)}dudv.$$ The Jacobian can be computed in 3D similarly, and is defined as the volume of the parallelepiped formed by the three partial derivatives of a three dimensional change-of-coordinates. Similar definitions hold in all dimensions, with the same application.

- Use the area of a parallelogram formula we developed to explain why the Jacobian can be computed using the formula $$\frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)} = \left|\frac{\partial x}{\partial u}\frac{\partial y}{\partial v}-\frac{\partial x}{\partial v}\frac{\partial y}{\partial u}\right|.$$

- For the polar coordinate transformation given by the change-of-coordinates $x=r\cos\theta$ and $y=r\sin\theta$, compute the differential $(dx,dy)$, and then show that the Jacobian is $\ds\frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (r,\theta)} = |r|$. This is precisely the reason we use the notation $dA = |r|drd\theta$ when setting up double integrals using polar coordinates.

- For the change-of-coordinates $x=2u-v$ and $y=u+2v$, compute the differential $(dx,dy)$, and then obtain the Jacobian $\ds \frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)}$.

- For the change-of-coordinates $x=au$ and $y=bv$, show that the Jacobian is $\ds \frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)}=|ab|$.

- For the change-of-coordinates $u=x+y$ and $v=x-y$, show that $\ds \frac{\partial (u,v)}{\partial (x,y)} = 2$.

- For the change-of-coordinates $u=x+y$ and $v=x-y$, first solve for $x$ and $y$ in terms of $u$ and $v$ (so obtain $x = ....$ and $y= ...$). Then show that $\ds \frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)} = \frac{1}{2}$.

Did you notice that $\ds \frac{\partial (u,v)}{\partial (x,y)} = \left(\ds \frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)}\right)^{-1}$?

Task 35.2

In three dimensions, some common coordinate systems are cylindrical and spherical coordinates. In this task, for each of these coordinates systems, we'll (1) develop the change-of-coordinates formula, (2) compute the Jacobian using the triple product, and then (3) use the Jacobian to compute the volume of an object in this coordinate system.

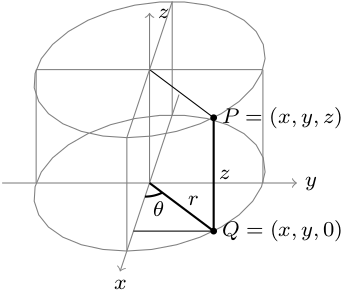

Let's first tackle cylindrical coordinates. Let $P=(x,y,z)$ be a point in space. This point lies on a cylinder of radius $r$, where the cylinder has the $z$ axis as its axis of symmetry. The height of the point is $z$ units up from the $xy$ plane. The point casts a shadow in the $xy$ plane at $Q=(x,y,0)$. The angle between the ray $\vec{Q}$ and the $x$-axis is $\theta$. See the image below.

- Explain why the equations for cylindrical coordinates are $$x=r\cos\theta, \quad y=r\sin\theta,\quad z=z.$$ [Hint: Compute the sine and cosine of $\theta$ in terms of $x$, $y$, and $r$, and then solve for $x$ and $y$.]

- Compute the Jacobian $\dfrac{\partial(x,y,z)}{\partial(r,\theta,z)}$ for cylindrical coordinates. The steps below are a guide, if needed.

- For cylindrical coordinates we have $x=r\cos\theta$, $y=r\sin\theta$, and $z=z$. Write the differential $d(x,y,z)$ as the linear combination of partial derivatives $$\begin{pmatrix}dx\\dy\\dz\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix}\cos\theta\\\sin\theta\\0\end{pmatrix}dr+\begin{pmatrix}?\\?\\?\end{pmatrix}d\theta+\begin{pmatrix}?\\?\\?\end{pmatrix}dz.$$

- Compute the volume of the parallelepiped formed by the three vectors (partial derivatives) above, using the triple product. Software can make quick work of this. Simplify your result to show that $\dfrac{\partial(x,y,z)}{\partial(r,\theta,z)} = |r|$.

- Consider the solid domain $D$ in space that lies inside the right circular cylinder $x^2+y^2=a^2$ (or $r=a$) for $0\leq z\leq h$. Start by drawing the domain $D$. The volume in cylindrical coordinates is given by the iterated integral $$V = \iiint_D dV = \ds\int_{0}^{2\pi}\int_{0}^{a}\int_{0}^{h}rdzdrd\theta.$$ Compute this integral to obtain a familiar formula $V = \pi a^2 h$.

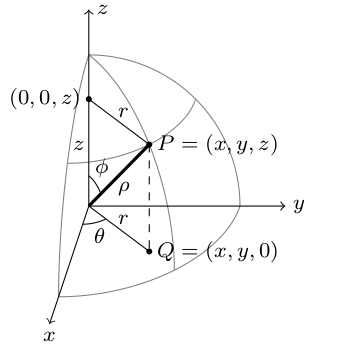

Now let's tackle spherical coordinates. Let $P=(x,y,z)$ be a point in space. This point lies on a sphere of radius $\rho$ ("rho"), where the sphere's center is at the origin $O=(0,0,0)$. The point casts a shadow in the $xy$ plane at $Q=(x,y,0)$. The angle between the ray $\vec{Q}$ and the $x$-axis is $\theta$, which some call the azimuth angle. The angle between the ray $\vec{P}$ and the $z$-axis is $\phi$ ("phi"), which some call the inclination angle, polar angle, or zenith angle. See the image below.

- Explain why the equations for spherical coordinates are $$x=\rho\sin\phi\cos\theta,\quad y=\rho\sin\phi\sin\theta,\quad z=\rho\cos\phi.$$ [Hint: Compute the sine and cosine of $\phi$ in terms of $\rho$, $r$, and $z$, and then solve for $r$ and $z$. Substitution into $x=r\cos\theta$ and $y=r\sin \theta$ will get the rest.]

- Compute the Jacobian $\dfrac{\partial(x,y,z)}{\partial(\rho,\phi,\theta)}$ for spherical coordinates. The steps below are a guide, if needed.

- For spherical coordinates we have $$x=\rho\sin\phi\cos\theta,\quad y=\rho\sin\phi\sin\theta,\quad z=\rho\cos\phi.$$ Write $d(x,y,z)$ as a linear combination of partial derivatives, so $$\begin{pmatrix}dx\\dy\\dz\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix}\sin\phi\cos\theta\\\sin\phi\sin\theta\\\cos\phi\end{pmatrix}d\rho+\begin{pmatrix}?\\?\\?\end{pmatrix}d\phi+\begin{pmatrix}?\\?\\?\end{pmatrix}d\theta.$$

- Compute the volume of the parallelepiped formed by the three vectors (partial derivatives) above. Software can make quick work of this. You can do it all by hand, but you'll have to use a Pythagorean identity several times to complete the simplification. Simplify your result to show that $\frac{\partial(x,y,z)}{\partial(\rho,\phi,\theta)} = |\rho^2\sin\phi|$.

- Consider the solid domain $D$ in space that lies inside the sphere $x^2+y^2+z^2=a^2$ (or $\rho=a$). Start by drawing the domain $D$. The volume in spherical coordinates is given by the iterated integral $$V = \iiint_D dV = \ds\int_{0}^{2\pi}\int_{0}^{\pi}\int_{0}^{a}\rho^2\sin\phi d\rho d\phi d\theta.$$ Compute this integral to obtain a familiar formula $V = \frac{4}{3}\pi a^3$.

There is some disagreement between different scientific fields about the notation for spherical coordinates. In some fields (like physics), $\phi$ represents the azimuth angle and $\theta$ represents the inclination angle, swapped from what we see here. In some fields, like geography, instead of the inclination angle, the elevation angle is given --- the angle from the $xy$-plane (lines of latitude are from the elevation angle). Additionally, sometimes the coordinates are written in a different order. You should always check the notation for spherical coordinates before communicating to others with them. As long as you have an agreed upon convention, it doesn't really matter how you denote them. See Wikipedia or MathWorld for a discussion of conventions in different disciplines.

Task 35.3

For a differentiable function $f(x)$, the second part of the fundamental theorem of calculus states that $\ds\int_a^b \frac{df}{dx} dx =f(b)-f(a)$. To find the total change in a function $f$ (so $f(b)-f(a)$), we just sum the little changes $\int_C df = \int_C \frac{df}{dx}dx$. We'll use this fact to greatly simplify work computations for vector fields that have a potential.

Let $\vec F$ be a vector field with $f$ being a potential for $\vec F$, meaning $\vec F = \vec \nabla f$. Let $\vec r(t)$ for $a\leq t\leq b$ be a differentiable parametrization of a curve $C$. Let $A = \vec r(a)$ and $B= \vec r (b)$ be the end points of the curve. The composite function $g(t) = f(\vec r(t)) = (f\circ \vec r)(t)$ gives the potential at points along the curve. In particular $f(A)$ and $f(B)$ give the potential at the end points of the curve. The difference in potential is $f(B)-f(A)$.

- Pause. Reread the above. Do you understand what each of $\vec F$, $f$, $\vec r$, $a$, $b$, $A$, $B$, and $g$ represent? If not, what parts do you have questions about? Then continue reading.

From the chain rule, the composite function $g(t) = f(\vec r(t)) = (f\circ \vec r)(t)$ has the derivative $\frac{dg}{dt}=\vec \nabla f(\vec r(t))\cdot\frac{d\vec r}{dt}$. We now compute $$\begin{align*} f(B)-f(A) &= f(\vec r(b))-f(\vec r(a))&\text{($A$ and $B$ are the end points of the curve)}\\ &= g(b)-g(a)&\text{(recall $g(t) = f(\vec r(t))$}\\ &= \int_a^b \frac{dg}{dt}dt&\text{(the fundamental theorem of calculus)}\\ &= \int_a^b \vec \nabla f(\vec r(t))\cdot \frac{d\vec r}{dt} dt&\text{(using the chain rule to compute $\frac{dg}{dt}$)}\\ &= \int_C \vec F\cdot d\vec r&\text{(recall that $\vec \nabla f=\vec F$)}. \end{align*}$$ This shows that the work done by $\vec F$ along $C$ is the difference in the potential $f$.

Suppose that $\vec F$ is a vector field that has a potential $f$ along a curve with differentiable parametrization $\vec r$ for $a\leq t\leq b$. Let $A = \vec r(a)$ and $B=\vec r(b)$ be the endpoints of the curve. Then we have $$\int_C \vec F\cdot d\vec r = \int_C \vec \nabla f \cdot d\vec r = f(B)-f(A).$$

Let's try using this theorem in a few situations.

- Let $\vec F(x,y) = (2x+y,x+4y)$ and $C$ be the parabolic path $\vec r(t) = (t,9-t^2)$ for $-3\leq t\leq 2$.

- Use the work formula we developed earlier in the semester, so $\int_C Mdx+Ndy$ or $\int_C \vec F\cdot d\vec r$, to set up and compute the work done by $\vec F$ along $\vec r$. This is a review of a previous learning target. Feel free to use software to complete the integral.

- Find a potential $f$ for $\vec F$, state $A$ and $B$, and then compute $f(B)-f(A)$.

- Identify the function $g(t) = f(\vec r(t))$, compute $\frac{dg}{dt}$, state $\vec F(\vec r(t))$ and $\frac{d\vec r}{dt}$, and then verify that $\frac{dg}{dt} = \vec F(\vec r(t))\cdot \frac{d\vec r}{dt}$ (these were the terms that appeared in the proof of the fundamental theorem of line integrals).

- Let $\vec F(x,y,z) = (2x+yz,2z+xz,2y+xy)$ and $C$ be the straight segment from $(2,-5,0)$ to $(1,2,3)$. Compute the work done by $\vec F$ along $C$ by first finding a potential for $\vec F$.

- Let $\vec F = (x,2yz,y^2)$. Let $C$ be the curve which starts at $(1,0,0)$ and follows a helical path $(\cos t, \sin t, t)$ to $(1,0,2\pi)$ and then follows a straight line path to $(2,4,3)$. Find the work done by $\vec F$ to get from $(1,0,0)$ to $(2,4,3)$ along this path.

- Suppose a vector field $\vec F$ has a potential. Compute $\int_C \vec F\cdot d\vec r$ where $C$ is the path parametrized by $\vec r(t) = (3\cos t, 3\sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 2\pi$.

Task 35.4

Pick some problems related to the topics we are discussing from the Text Book Practice page.