- I-Learn, Class Pictures, Learning Targets, Text Book Practice

- Prep Tasks: Unit 1 - Motion, Unit 2 - Derivatives, Unit 3 - Integration, Unit 4 - Vector Calculus

We still have some tasks from Day 37 to finish discussing in class.

Day 37 - Prep

Task 37.1

- Consider the region that lies below the $z$-axis and between 2 spheres of radii $a$ and $b$ with $a<b$. The image below shows such a region where the inner radius is $a=3$, and the outer radius is $b=5$.

- Set up an iterated triple integral in spherical coordinates to compute the volume of this region.

- Set up an iterated triple integral formula to compute the $z$-coordinate of the centroid (symmetry gives us $\bar x = \bar y = 0$).

- If the temperature at points in this region is given by $T(x,y,z) = x+3$, then set up an iterated triple integral formula that would give the average temperature of the region.

- A metal casing lies inside the cylinder $x^2+y^2=4$, outside the cylinder $x^2+y^2=1$, below the paraboloid $z=9-x^2-y^2$, and above the plane $z=0$. The region is shown below, where one quarter of the region was removed so you can see the hollow interior.

- Set up an iterated integral in cylindrical coordinates to compute the volume of the casing.

- The casing is made of a composite material and the density of the casing is more dense the further from the center. The density is given by $\delta(x,y,z) = x^2+y^2$. Set up an iterated triple integral formula to compute the $z$-coordintate of the center-of-mass of the casing.

Remember that you can verify that your bound are correct by using Mathematica to draw whatever you decide the bounds should be. Here's two examples of how to construct regions, the first in cylindrincal coordinates, and the second in spherical coordinates.

coordinates = {r Cos[theta], r Sin[theta], z}

R = ParametricRegion[coordinates, {{r, 1, 3}, {theta, Pi/2, 2 Pi}, {z, 0, r}}];

Region[R, Axes -> True, AxesLabel -> {x, y, z}, AxesOrigin -> {0, 0, 0}]

Integrate[r, {r, 1, 3}, {theta, Pi/2, 2 Pi}, {z, 0, r}]

coordinates = {rho Sin[phi] Cos[theta], rho Sin[phi] Sin[theta], rho Cos[phi]}

R = ParametricRegion[coordinates, {{theta, 0, Pi/2}, {phi, Pi/6, Pi/3}, {rho, 1, 3}}];

Region[R, Axes -> True, AxesLabel -> {x, y, z}, AxesOrigin -> {0, 0, 0}]

Integrate[rho^2 Sin[phi], {theta, 0, Pi/2}, {phi, Pi/6, Pi/3}, {rho, 1, 3}]

If the code above is extremely slow on your computer, then you can use the code below instead. The code is more complicated, as it plots the six surfaces defined by the bounds you choose, but the code used requires very minimal processing (it works fast). (The Evaluate[] command is needed for the code to work prior to Mathematica 13.)

plotRegion3D[cs_, ob_, mb_, ib_] :=

Show[{{ParametricPlot3D[Evaluate[Table[cs /. (ib[[1]] -> ib[[i]]), {i, 2, 3}], ob, mb], AxesLabel -> {x, y, z}, Mesh -> {15, 1}],

ParametricPlot3D[Evaluate[Table[(cs /. (ib[[1]] -> (ib[[2]] (1 - s) + ib[[3]] s))) /. (mb[[1]] -> mb[[i]]), {i, 2, 3}], ob], {s, 0, 1}, PlotStyle -> {Red, Blue}, Mesh -> {15, 0}],

ParametricPlot3D[Evaluate[Table[(cs /. (ib[[1]] -> (ib[[2]] (1 - s) + ib[[3]] s))) /. (mb[[1]] -> (mb[[2]] (1 - t) + mb[[3]] t)) /. (ob[[1]] -> ob[[i]]), {i, 2, 3}]], {t, 0, 1}, {s, 0, 1}, PlotStyle -> Green, Mesh -> {0, 0}]}}, PlotRange -> All]

coordinates = {r Cos[theta], r Sin[theta], z}

plotRegion3D[coordinates, {r, 1, 3}, {theta, Pi/2, 2 Pi}, {z, 0, r}]

coordinates = {rho Sin[phi] Cos[theta], rho Sin[phi] Sin[theta], rho Cos[phi]}

plotRegion3D[coordinates, {theta, 0, Pi/2}, {phi, Pi/6, Pi/3}, {rho, 1, 3}]

Much simpler code will draw 2D regions

plotRegion[cs_, ob_, ib_] := ParametricPlot[Evaluate[cs, ob, ib], Mesh -> {10, 0}]

coordinates = {r Cos[theta], r Sin[theta]};

plotRegion[coordinates, {theta, Pi/4, Pi}, {r, 2, 5}]

Task 37.2

- Consider the region $R$ in space satisfying $0\leq x-y\leq 4$ and $1\leq 2x+y\leq 3$. We wish to evaluate the integral $\ds\iint_R xy dA$.

- Draw the region $R$.

- Using the change-of-coordinates $u=x-y$ and $v=2x+y$, compute the Jacobian $\frac{\partial(u,v)}{\partial (x,y)}$.

- Find $x$ and $y$ in terms of $u$ and $v$.

- Use this change-of-coordinates to compute $\ds\iint_R xy dA$ by first setting up an appropriate iterated integral of the form $\ds \int_{?}^{?}\int_{?}^{?}?dudv$.

- Consider the ellipsoid $\ds\frac{x^2}{a^2}+\frac{y^2}{b^2}+\frac{z^2}{c^2}=1$, for some positive constants $a$, $b$, and $c$.

- Draw the region.

- Using the change-of-coordinates $x = a u \sin v \cos w$, $y = b u \sin v \sin w$, $x = c u \cos v$, compute the Jacobian $\frac{\partial (x,y,z)}{\partial (u,v,w)}$. Feel free to use software to help you.

- Set up an iterated integral using $uvw$-coordinates to compute the volume inside the ellipsoid. Then compute the integral.

- Set up an iterated integral using $uvw$-coordinates to show that $\bar z = \frac{3c}{16}$ for the region inside the ellipsoid that is above the $xy$-plane.

Task 37.3

When you can use a potential to compute work, it greatly simplifies things.

- As you complete each problem below, first ask if there is a potential.

- Compute the work done by the vector field $\vec F(x,y) = (y,x)$ on a object that moves along the path $\vec r(t) = (\cos t, \sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 2 \pi$.

- Compute the work done by the vector field $\vec F(x,y) = (-y,x)$ on a object that moves along the path $\vec r(t) = (\cos t, \sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 2 \pi$.

- For each vector field above, use Mathematica to construct an image that shows the vector field along with the curve in the same plot. (You'll need VectorPlot[] and ParametricPlot[], with Show[] to get them in the same plot).

We've seen that if a vector field has a potential, then the derivative is symmetric. Is the converse of this statement true, namely if the derivative of a vector field is symmetric, then does that mean the vector field has a potential?

- Consider the vector field $\ds\vec F(x,y) = \left(\frac{-y}{x^2+y^2},\frac{x}{x^2+y^2}\right)$.

- Show that the derivative is symmetric.

- Compute the work done by the vector field $\vec F(x,y)$ on a object that moves along the path $\vec r(t) = (\cos t, \sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 2 \pi$.

- Explain why $\vec F(x,y)$ does not have a potential.

- Look up "simply connected region" (see section 6.3), and explain why the domain of $\ds\vec F(x,y) = \left(\frac{-y}{x^2+y^2},\frac{x}{x^2+y^2}\right)$ is NOT simply connected.

When the domain of a continuously differentiable vector field is simply connected, then the vector field has a potential if and only if the derivative is symmetric. The concept of a simply connected domain is the start of an entire branch of mathematics called algebraic topology, all stemming from the question, "under what circumstances can we guarantee that a vector field will have a potential?"

Task 37.4

Pick some problems related to the topics we are discussing from the Text Book Practice page.

We still have some tasks from Day 38 to finish discussing in class.

Day 38 - Prep

Task 38.1

The shell method and disc method are two methods for computing the volume of a solid of revolution using a single integral. As a solid of revolution has volume, then a triple integral will give the volume, provided we can set up appropriate bounds. In this task, we'll see that the only difference between the shell and disc methods are the order in which a triple integral is done. If you've forgotten (which is completely normal), here's a reminder.

- The shell-method computes volumes with $$V = \int dV = \int_a^b \underbrace{(2\pi r)(\text{height of shell at $r$})}_{\text{shell surface area = (circumference)(height)}} \underbrace{dr}_{\text{shell thickness}}.$$

- The disc-method computes volumes with $$V = \int dV =\int_a^b \underbrace{\pi (\text{radius of disc at height $z$})^2}_{\text{area of disc at height $z$}} \underbrace{dz}_{\text{little height}}.$$

- Consider the solid region in space that is bounded above by $z=9-x^2-y^2$ (so $z=9-r^2$) and below by the $xy$-plane. In Cartesian coordinates, the volume of this region is given by $$\int_{-3}^{3}\int_{-\sqrt{9-x^2}}^{\sqrt{9-x^2}}\int_{0}^{9-x^2-y^2}dzdydx.$$ This region is formed by taking the region under the parabola $z=9-r^2$ (above the plane $z=0$) and revolving it about the $z$-axis.

- Set up a triple integral in cylindrical coordinates to compute the volume of this solid using the order $d\theta dzdr$.

- Compute the two inside integrals and simplify to show that $V = \int_{0}^{3} 2\pi r (9-r^2) dr$.

- Set up a triple integral in cylindrical coordinates to compute the volume of this solid using the order $d\theta drdz$. You will end up with $r=\sqrt{9-z}$ as one of the bounds.

- Compute the two inside integrals and simplify to show that $V = \int_{0}^{9} \pi (\sqrt{9-z})^2 dz$.

- Which order above uses the shell method, and which uses the disc method?

- Consider the region in space that satisfies $0\leq a\leq r\leq b$ with $g(r)\leq z\leq f(r)$.

- Construct a sketch of such a region. You get to pick and illustrate what $a$, $b$, $g(r)$, and $f(r)$ mean.

- Set up a triple integral in cylindrical coordinates to compute the volume of this solid using the order $d\theta dzdr$.

- Compute the two inside integrals to obtain a formula for the volume that involves a single integral in terms of $r$.

- Consider the region in space that satisfies $c\leq z\leq d$ with $0\leq g(z)\leq r\leq f(z)$.

- Construct a sketch of such a region. You get to pick and illustrate what $c$, $d$, $g(z)$, and $f(z)$ mean.

- Set up a triple integral in cylindrical coordinates to compute the volume of this solid using the order $d\theta drdz$.

- Compute the two inside integrals to obtain a formula for the volume that involves a single integral in terms of $z$.

Task 38.2

- Consider the integral $\ds \int_{0}^{4}\int_{0}^{4-x} e^{(x+y)^2}dydx$ and the change-of-coordinates $u=x$, $v=x+y$.

- Solve for $x$ and $y$ in terms of $u$ and $v$, and then compute $\frac{\partial(x,y)}{\partial(u,v)}$.

- Set up the corresponding iterated integral using the order $dvdu$. Then set up the corresponding integral using the order $dudv$.

- Compute the simpler of the two integrals you just set up.

- Consider the integral $\ds \iint_R xy dA$ for the region $R$ that lies inside the triangle with vertices $(0,0)$, $(2,4)$, and $(3,-3)$. Notice that two of the edges of the triangle lie on the lines $y=2x$ and $y=-x$, which means we'll use the change-of-coordinates $u=2x-y$, $v=x+y$.

- Sketch the region $R$ in the $xy$-plane. Then sketch the corresponding region in the $uv$-plane (you should obtain a triangle).

- Set up an iterated integral using $uv$-coordinates to compute $\ds \iint_R xy dA$.

- Compute the integral.

Task 38.3

This task focuses on exploring the curl and divergence of a vector field, using Mathematica, to gain some geometric intuition about what these vectors compute.

- For each vector field below, compute the curl of the vector field, modify this chunk of Mathematica code to visualize the vector field and the curl, and look for relationships between $\vec F$ and $\vec\nabla \times \vec F$.

F[x_, y_, z_] := {-y, x, 0} Show[VectorPlot3D[Evaluate[F[x, y, z]], {x, -1, 1}, {y, -1, 1}, {z, -1, 1}, VectorAspectRatio -> 1/8], VectorPlot3D[Evaluate[Curl[F[x, y, z], {x, y, z}]], {x, -1, 1}, {y, -1, 1}, {z, -1, 1}, VectorPoints -> Coarse, VectorAspectRatio -> 1/4]]- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (-y,x,0)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (-y,x,0)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (-z, 0, 2 x)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (2x, 3y, 4z)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (0, 3 z, -4 y)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (-z, z, x - y)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (y - z, -x + z, x - y)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (y^2, -x, 0)$

- Pick your own vector field.

- Summarize what relationships, if any, you saw.

- For each vector field below, compute the divergence of the vector field, modify this chunk of Mathematica code to visualize the vector field, and look for relationships between $\vec F$ and $\vec\nabla \cdot \vec F$.

F[x_, y_, z_] := {2 x, 0, 0} VectorPlot3D[Evaluate[F[x, y, z]], {x, -1, 1}, {y, -1, 1}, {z, -1, 1}]- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (2x,0,0)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (0,-3y,0)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (0,0,4z)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (2x,-3y,4z)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (x,y,z)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (-y,x,0)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (x^2,0,0)$

- Pick your own vector field.

- Summarize what relationships, if any, you saw.

Task 38.4

Pick some problems related to the topics we are discussing from the Text Book Practice page.

Day 39 - Prep

There are no new tasks for this day. Work on the tasks from previous days that we have not yet discussed in class.

Day 39 - In class

Brain Gains (Rapid Recall, Jivin' Generation)

- Consider the region $R$ in the first quadrant that lies above the curves $y=x$ and $y=\frac{1}{x}$, and below the curves $y=3x$ and $y=\frac{4}{x}$. Note that we can rewrite $x\leq y\leq 3x$ as $1\leq \frac{y}{x}\leq 3$, and we can rewrite $\frac{1}{x}\leq y\leq \frac{4}{x}$ as $1\leq xy\leq 4$. Using the change-of-coordinates $u = xy$ and $v=\frac{y}{x}$, compute the integral $\ds\iint_R dA$.

Solution

Computing differentials gives us $$\begin{pmatrix}du\\dv\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix}y\\-y/x^2\end{pmatrix}dx+\begin{pmatrix}x\\1/x\end{pmatrix}dy = \begin{bmatrix}y&x\\-y/x^2&1/x\end{bmatrix}\begin{pmatrix}dx\\dy\end{pmatrix}.$$ The Jacobian of the transformation is $$\frac{\partial (u,v)}{\partial(x,y)} = |(y)(1/x) - (-y/x^2)(x)| = |2(y/x)| = |2v| = 2v.$$ We need $\ds \frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial(u,v)} = \frac{1}{2v},$ which gives $$\iint_R dA = \iint \frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial(u,v)} dudv = \int_{1}^{3}\int_{1}^{4}\frac{1}{2v}dudv.$$ Software can quickly compute this integral. Here is some Mathematica code that draws the region, and then computes the integral in three different ways.

R = ImplicitRegion[1 <= x y <= 4 && 1 <= y/x <= 3 && x >= 0, {x, y}]

Show[Plot[{1/x, 4/x, 3 x, x}, {x, 0, 4}, PlotRange -> {0, 4}], Region[R]]

(*Integrate using the change-of-coordiantes.*)

Integrate[1/(2 v), {v, 1, 3}, {u, 1, 4}] // N

(*Integrate using Mathematica's region utilities.*)

Integrate[1, {x, y} \[Element] R] // N

(*Compute the integral by splitting the region up into 3 Cartesian regions.*)

Integrate[1, {x, Sqrt[1/3], 1}, {y, 1/x, 3 x}] +

Integrate[1, {x, 1, Sqrt[4/3]}, {y, x, 3 x}] +

Integrate[1, {x, Sqrt[4/3], 2}, {y, x, 4/x}] // N

Here is a way to visualize the region that shows the images of 1 by 1 boxes from the $uv$-plane, and 1/4 by 1/4 boxes, so we can visualize what the Jacobian $\frac{1}{2v}$ actually means.

coordinates = {Sqrt[u /v], Sqrt[u v]};

ParametricPlot[Evaluate[coordinates, {u, 1, 4}, {v, 1, 3}], Mesh -> 1 {3, 2} - {1, 1}]

coordinates = {Sqrt[u /v], Sqrt[u v]};

ParametricPlot[Evaluate[coordinates, {u, 1, 4}, {v, 1, 3}], Mesh -> 4 {3, 2} - {1, 1}]

- Consider the region $R$ that lies inside the triangle with vertices $(0,1)$, $(1,-2)$, and $(2,3)$, and the change-of-coordinates $u=x-y+1$, $v=3x+y-1$. (These coordinates were obtained by finding an equation of the lines of two edges of the triangle.) Show that $\ds \frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial(u,v)} = \frac{1}{4}$, and then fill in the missing bounds of the integral $$\ds\iint_R 3x+y dA = \int_{0}^{?}\int_{0}^{?}(v+1)(\frac{1}{4})dvdu.$$

Solution

The Jacobian of $u$ and $v$ with respect to $x$ and $y$ is the area of the parallelogram with edges equal to $\frac{\partial (u,v)}{\partial x}=(1,3)$ and $\frac{\partial (u,v)}{\partial y}=(-1,1)$, which is $A = |(1)(1)-(3)(-1)|=4$. This gives $\ds \frac{\partial (u,v)}{\partial(x,y)} = 4$, and hence we have $\ds \frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial(u,v)} = \frac{1}{4}$.

To find the bounds, we need to figure out where the points $(0,1)$, $(1,-2)$, and $(2,3)$ lie in the $(u,v)$ plane.

- The point $(x,y)=(0,1)$ is at $u=0-1+1 = 0$ and $v=3(0)+1-1 = 0$, so $(u,v)=(0,0)$, the origin of our new coordinate system.

- The point $(x,y)=(1,-2)$ is at $u=1-(-2)+1 = 4$ and $v=3(1)+(-2)-1 = 0$, so $(u,v)=(4,0)$.

- The point $(x,y)=(2,3)$ is at $u=2-(3)+1 = 4$ and $v=3(2)+(3)-1 = 0$, so $(u,v)=(0,8)$.

The three points form a triangle in the $uv$-plane. The top edge of that triangle is the line $v=8-2u$. As such, we have $$\ds\iint_R 3x+y dA = \int_{0}^{4}\int_{0}^{8-2u}(v+1)(\frac{1}{4})dvdu.$$

coordinates = {(u + v)/4, (v - 3 u + 4)/4};

ParametricPlot[Evaluate[coordinates, {u, 0, 4}, {v, 0, 8 - 2 u}], Mesh -> {10, 0}]

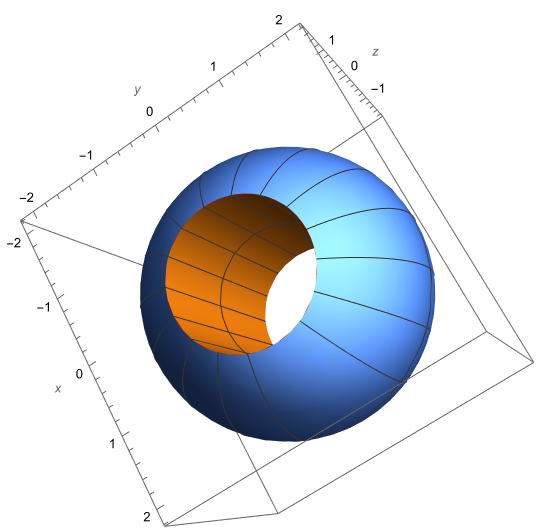

- A bead is formed by drilling a hole through a sphere. The solid region shown below is the region inside a sphere of radius 2 and outside a cylinder of radius 1. Set up an iterated triple integral in spherical coordinates that would give the volume of the solid.

Solution

The sphere has equation $\rho = 2$. The cylinder has equation $r=1$ or rather $\rho \sin \phi = 1$, which we can rewrite at $\rho = \csc \phi$. The two surfaces intersect when $\sin\phi = \frac{1}{2}$, so when $\phi = \pi/6$ and $\phi = 5\pi/6$. The volume is given by the integral $$V=\int_{0}^{2\pi}\int_{\pi/6}^{5\pi/6}\int_{\csc \phi}^{2}\rho^2\sin\phi d\rho d\phi d\theta.$$

We can check our solution is correct by drawing the region with Mathematica. The code below uses the custom function plotRegion3D[]. You can also use the built in ParametricRegion[] command (see a previous day for examples).

plotRegion3D[cs_, ob_, mb_, ib_] :=

Show[{{ParametricPlot3D[Evaluate[Table[cs /. (ib[[1]] -> ib[[i]]), {i, 2, 3}], ob, mb], AxesLabel -> {x, y, z}, Mesh -> {15, 1}],

ParametricPlot3D[Evaluate[Table[(cs /. (ib[[1]] -> (ib[[2]] (1 - s) + ib[[3]] s))) /. (mb[[1]] -> mb[[i]]), {i, 2, 3}], ob], {s, 0, 1}, PlotStyle -> {Red, Blue}, Mesh -> {15, 0}],

ParametricPlot3D[Evaluate[Table[(cs /. (ib[[1]] -> (ib[[2]] (1 - s) + ib[[3]] s))) /. (mb[[1]] -> (mb[[2]] (1 - t) + mb[[3]] t)) /. (ob[[1]] -> ob[[i]]), {i, 2, 3}]], {t, 0, 1}, {s, 0, 1}, PlotStyle -> Green, Mesh -> {0, 0}]}}, PlotRange -> All]

coordinates = {rho Sin[phi] Cos[theta], rho Sin[phi] Sin[theta], rho Cos[phi]}

plotRegion3D[coordinates, {theta, 0, 2 Pi}, {phi, Pi/6, 5 Pi/6}, {rho, Csc[phi], 2}]

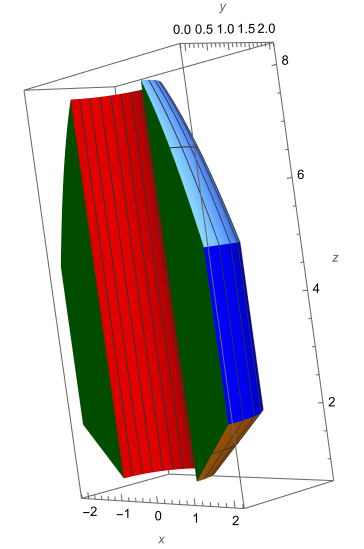

- Consider the 2D region in the $yz$-plane satisfying $1\leq y \leq 2$ and $y\leq z\leq 9-y^2$. This region is revolved about the $z$-axis to produce a solid of revolution. Set up a triple integral in cylindrical coordinates that would give the volume of this solid. Half of the region is shown below.

Solution

The volume is $$V=\int_{0}^{2\pi}\int_{1}^{2}\int_{r}^{9-r^2}r dz dr d\theta.$$

We can check our solution is correct by drawing the region with Mathematica, using the custom function plotRegion3D[] (defined in the previous question).

coordinates = {r Cos[theta], r Sin[theta], z}

plotRegion3D[coordinates, {theta, 0, 2 Pi}, {r, 1, 2}, {z, r, 9-r^2}]

Group Problems

- Consider the solid of revolution obtained by revolving about the $z$-axis the 2D region in the $xz$-plane that lies below the line $z = 4-x$ for $2\leq x\leq 4$.

- Set up an iterated triple integral in cylindrical coordinates using the order $d\theta dz dr$ that would give the volume of this solid.

- Set up an iterated triple integral in cylindrical coordinates using the order $d\theta dr dz$ that would give the volume of this solid.

- Use Mathematica to verify that the bounds you gave do indeed correctly describe the solid.

- Compute one of the integrals above by hand (feel free to check with software).

- Consider the region $R$ in the plane that lies inside the triangle with corners $(0,0)$, $(1,2)$, and $(-3,1)$. Two edges are given by the lines $2x-y=0$ and $x+3y=0$, so let's use the change-of-coordinates $u=2x-y$ and $v=x+3y$.

- Compute $\ds \frac{\partial (u,v)}{\partial(x,y)}$ and $\ds \frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial(u,v)}$.

- Draw the region $R$ in the $uv$-plane.

- Use the change-of-coordinates to set up an appropriate integral in terms of $u$ and $v$ to compute $\iint_R xy dA$.

- Consider the vector field $\ds \vec F = \frac{1}{2\pi}\left(\frac{-y}{x^2+y^2},\frac{x}{x^2+y^2}\right)$.

- Let $C$ be the curve parametrized by $\vec r(t) = (3\cos t, 3\sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 2\pi$. Compute the work done by $\vec F$ to move an object along $C$. [Hint: The answer is NOT zero.]

- Let $C$ be the curve parametrized by $\vec r(t) = (7\cos t, 7\sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 4\pi$. Compute the work done by $\vec F$ to move an object along $C$.

- Let $C$ be the curve parametrized by $\vec r(t) = (a\cos t, a\sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 2k\pi$. Compute the work done by $\vec F$ to move an object along $C$.

- Show that $D\vec F(x,y)$ is symmetric.

- Does $\vec F$ have a potential?

Solutions

If $\vec F$ had a potential, then the work done along a closed curve would be zero. This is not true, as the first 3 parts illustrate. The vector field does NOT have a potential.

The function and derivative are not defined at $(0,0)$, which means the domain of the vector field is not simply connected. We cannot use the symmetry of the derivative to conclude that there is a potential, because the domain is not simply connected.

Here are some Mathematica computations relevant to this problem.

ClearAll[F, r]

F[x_, y_] := 1/(2 Pi (x^2 + y^2)) {-y, x}

r[t_] := {a Cos[t], a Sin[t]}

(*Is the derivative symmetric*)

D[F[x, y], {{x, y}}] // Simplify // MatrixForm

(*Try to find a potential*)

Integrate[F[x, y][[1]], x]

Integrate[F[x, y][[2]], y]

(*Compute work done by wrapping k times around a circle of radius a*)

Dot[F @@ r@t, D[r[t], t]] // Simplify

Integrate[Dot[F @@ r@t, D[r[t], t]], {t, 0, 2 k Pi}]

Day 40 - Prep

Learning Target Checkoff

A learning target quiz will appear in I-Learn. Complete and submit the quiz before the due date.

|

Sun |

Mon |

Tue |

Wed |

Thu |

Fri |

Sat |