As you work through tasks, remember that you can use the Text Book Practice page to find relevant exercises in the text that you can use to help you with topics you have questions on.

Task 1

Recall that the gradient of a function $f$ is the quantity $\vec \nabla f = \left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x},\frac{\partial f}{\partial y},\frac{\partial f}{\partial z} \right) = \left(\frac{\partial }{\partial x},\frac{\partial }{\partial y},\frac{\partial }{\partial z} \right)f,$ where in the last expression we let $\vec \nabla = \left(\frac{\partial }{\partial x},\frac{\partial }{\partial y},\frac{\partial }{\partial z} \right)$ and then treat $\vec \nabla f$ as a "vector" $\vec \nabla$ times a scalar $f$. The quantity $\vec \nabla = \left(\frac{\partial }{\partial x},\frac{\partial }{\partial y},\frac{\partial }{\partial z} \right)$ is an example of something we call an "operator," something that operates on functions.

An operator is a function whose input is a function itself. This allows us to say "operator on functions" instead of "function of functions."

We've already encountered several operators before this class. For example, the derivative operator $\frac{d}{dx}$ from first semester calculus takes a function such as $f(x) = x^2$ and returns a new function $\frac{d}{dx}f = 2x$. The integral operator $\int_a^b f dx$ takes a function $f$ and return a real number. The gradient operator takes a function $f$ and returns a vector of functions $\vec \nabla f = (f_x,f_y,f_z)$. This is just 3 examples of operators. Here are two more.

Consider the vector field $\vec F(x,y,z) = (M,N,P)$, where $M$, $N$, and $P$ are functions of $x$, $y$, and $z$.

- The divergence of $\vec F$ is the scalar quantity $$ \begin{align*} \text{div}(\vec F) &= \vec \nabla \cdot \vec F \\ &= \left(\frac{\partial }{\partial x},\frac{\partial }{\partial y},\frac{\partial }{\partial z} \right)\cdot \left(M,N,P\right) \\ &= \frac{\partial M}{\partial x}+\frac{\partial N}{\partial y}+\frac{\partial P}{\partial z}\\ &= M_x+N_y+P_z . \end{align*} $$

- The curl of $\vec F$ is the vector quantity $$ \begin{align*} \text{curl}(\vec F) &= \vec \nabla \times \vec F \\ &= \left(\frac{\partial }{\partial x},\frac{\partial }{\partial y},\frac{\partial }{\partial z} \right)\times \left(M,N,P\right) \\ &= \left(\frac{\partial P}{\partial y}-\frac{\partial N}{\partial z},\frac{\partial M}{\partial z}-\frac{\partial P}{\partial x},\frac{\partial N}{\partial x}-\frac{\partial M}{\partial y}\right) \\ &= \left(P_y-N_z,M_z-P_x,N_x-M_y\right) . \end{align*} $$

We will often say "del dot F" for the divergence of $\vec F$, and "del cross F" for the curl of $\vec F$.

Use the definitions above to compute the divergence and curl of each vector field below. Then compute the derivative (which will be a 3 by 3 matrix). Finish by checking your work with Mathematica (code for doing so is provided below). If you see any relationships worth mentioning, articulate them in your work.

- $\vec F = (2x, 3y^2, e^z)$

- $\vec F = (-3y, 3x, 5z)$

- $\vec F = (z-3y, 3x, -x)$

In class, we'll talk about the physical meaning of each result above.

The code below computes the derivative, divergence, and curl of the vector field $\vec F = (x^2 y, x y z, 3 x + 4 z)$.

F[x_, y_, z_] := {x^2 y, x y z, 3 x + 4 z}

D[F[x, y, z], {{x, y, z}}] // MatrixForm

Div[F[x, y, z], {x, y, z}]

Curl[F[x, y, z], {x, y, z}]

Task 2

Many vector fields are the derivative of a function. This function we call a potential for the vector field. Once we are comfortable finding potentials, we'll show that the work done by a vector field with a potential is the difference in the potential.

A potential for the vector field $\vec F$ is a function $f$ whose gradient equals $\vec F$, so $\vec \nabla f=\vec F$.

Let's practice finding gradients and potentials. You're welcome to watch this YouTube Video before starting, or just jump in and give it a try.

- Let $f(x,y) = x^2+3xy+2y^2$. Find $\vec \nabla f$. Then compute $D^2f(x,y)$ (you should get a square matrix). What are $f_{xy}$ and $f_{yx}$?

- Consider the vector field $\vec F(x,y)=(2x+y,x+4y)$. Find the derivative of $\vec F(x,y)$ (it should be a square matrix). Then find a function $f(x,y)$ whose gradient is $\vec F$ (i.e. $Df=\vec F$). What are $f_{xy}$ and $f_{yx}$?

- Consider the vector field $\vec F(x,y)=(2x+y,3x+4y)$. Find the derivative of $\vec F$. Why is there no function $f(x,y)$ so that $Df(x,y)=\vec F(x,y)$? [Hint: look at $f_{xy}$ and $f_{yx}$.]

Let $\vec F$ be a vector field that is everywhere continuously differentiable. Then $\vec F$ has a potential if and only if the derivative $D\vec F$ is a symmetric matrix. We say that a matrix is symmetric if interchanging the rows and columns results in the same matrix (so if you replace row 1 with column 1, and row 2 with column 2, etc., then you obtain the same matrix).

- For each of the following vector fields, start by computing the derivative. Then find a potential, or explain why none exists.

- $\vec F(x,y)=(2x-y, 3x+2y)$

- $\vec F(x,y)=(2x+4y, 4x+3y)$

- $\vec F(x,y)=(2x+4xy, 2x^2+y)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z)=(x+2y+3z,2x+3y+4z,2x+3y+4z)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z)=(x+2y+3z,2x+3y+4z,3x+4y+5z)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z)=(x+yz,xz+z,xy+y)$

The Mathematica code below starts by computing the derivative $D\vec F$, then uses DSolve to find a potential, and finishes by computing the gradient of the potential to see if it is the original vector field (verify you have the correct solution). If a potential exists, then the last line should match the first. You'll need to add a third variable (,z) in appropriate spots to use this code for a 3D vector field.

ClearAll[F, f, x, y]

F[x_, y_] := {2 x + y, x + 4 y}

D[F[x, y], {{x, y}}] // MatrixForm

potential = DSolve[D[f[x, y], {{x, y}}] == F[x, y], f[x, y], {x, y}]

D[f[x, y] /. potential, {{x, y}}] // Flatten

Task 3

We've already learned how to draw parametric space curves, such as $\vec r(t)=(2\cos t, 2\sin t, t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 4\pi$. We pick several values of $t$, plot the corresponding points in space, and then connect the dots. We can draw this function in Mathematica using the following code.

ParametricPlot3D[{2 Cos[t], 2 Sin[t], t}, {t, 0, 4 Pi}]

The example above draws a wire, or path, in space. It's an example of a parametrization that uses only one parameter. Because only one parameter is used, the graph represents an object for which it makes sense to compute lengths. It's like we've wrapped a straight line up in space, using the parametrization. What happens if we increase the number of parameters. That's what this task explores.

- Suppose a jet begins spiraling upwards to gain height. The position of the jet after $t$ seconds is modeled by the equation $\vec r(t)=(2\cos t, 2\sin t, t).$ The jet is accompanied by several jets flying side by side. As all the jets fly, they leave a smoke trail behind them (it's an air show). The smoke from each jet spreads outwards to mix together, so that it looks like the jets are leaving a wide sheet of smoke behind them as they spiral upwards. The position of two of the many other jets is given by $\vec r_3(t)=(3\cos t, 3\sin t, t)$ and $\vec r_4(t)=(4\cos t,4\sin t,t)$. A function which represents the smoke stream from these jets is $\vec r(a,t)=(a\cos t, a\sin t, t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 4\pi$ and $2\leq a\leq 4$.

- Graph the position of the three jets $\vec r(2,t)=(2\cos t, 2\sin t, t)$, $\vec r(3,t)=(3\cos t, 3\sin t, t)$, and $\vec r(4,t)=(4\cos t,4\sin t,t)$ in the same 3D plot.

- Let $t=0$ and graph the curve $r(a,0)=(a,0,0)$ for $a\in[2,4]$ (so $2\leq a\leq 4$), which represents a segment along which the smoke has spread. Then repeat this for $t=\pi/2$, then $t=\pi$, and then $t=3\pi/2$.

- Describe the resulting surface. Then use Mathematica to view the surface (all it requires is adding another parameter to the code).

ParametricPlot3D[{a Cos[t], a Sin[t], t}, {t, 0, 4 Pi}, {a, 2, 4}]

We call the surface you drew above a parametric surface. The vector equation describing the smoke screen is a parametrization of this surface.

A parametrization of a surface is a collection of three equations to tell us the position $$x=x(u,v), y=y(u,v), z=z(u,v)$$ of a point $(x,y,z)$ on the surface. We call $u$ and $v$ parameters, and these parameters give us a two dimensional pair $(u,v)$, the input, needed to obtain a specific location $(x,y,z)$, the output, on the surface. We can also write a parametrization in vector form as $$\vec r(u,v) = (x(u,v), y(u,v), z(u,v)).$$ We'll often give bounds on the parameters $u$ and $v$, which help us describe specific portions of the surface. A parametric surface is a surface together with a parametrization.

We draw parametric surfaces by joining together many parametric space curves. Pick one variable, hold it constant, and draw the resulting space curve. Repeat this several times, and you'll have a 3D surface plot. Most of 3D computer animation is done using parametric surfaces. Car companies create computer models of vehicles using parametric surfaces, and then use those parametric surfaces to study collisions. Often the mathematics behind these models is hidden in the software program, but parametric surfaces are at the heart of just about every 3D model.

- Consider the parametric surface $\vec r(u,v)=(u\cos v, u\sin v, u^2)$ for $0\leq u\leq 3$ and $0\leq v\leq 2 \pi$. Construct a graph of this function.

- Remember, to do so we just let $u$ equal a constant (such as 1, 2, 3) and then graph the resulting space curve where we let $v$ vary. After doing this for several values of $u$, swap and let $v$ equal a constant (such as 0, $\pi/2$, etc.) and graph the resulting space curve as $u$ varies.

- Did you get a satellite dish? Modify the Mathematica code above to have software construct the surface.

Task 4

For a differentiable function $f(x)$, the second part of the fundamental theorem of calculus states that $\ds\int_a^b \frac{df}{dx} dx =f(b)-f(a)$. To find the total change in a function $f$ (so $f(b)-f(a)$), we just sum the little changes $\int_C df = \int_C \frac{df}{dx}dx$. We'll use this fact to greatly simplify work computations for vector fields that have a potential.

Let $\vec F$ be a vector field with $f$ being a potential for $\vec F$, meaning $\vec F = \vec \nabla f$. Let $\vec r(t)$ for $a\leq t\leq b$ be a differentiable parametrization of a curve $C$. Let $A = \vec r(a)$ and $B= \vec r (b)$ be the end points of the curve. The composite function $g(t) = f(\vec r(t)) = (f\circ \vec r)(t)$ gives the potential at points along the curve. In particular $f(A)$ and $f(B)$ give the potential at the end points of the curve. The difference in potential is $f(B)-f(A)$.

- Pause. Reread the above. Do you understand what each of $\vec F$, $f$, $\vec r$, $a$, $b$, $A$, $B$, and $g$ represent? If not, what parts do you have questions about? Then continue reading.

From the chain rule, the composite function $g(t) = f(\vec r(t)) = (f\circ \vec r)(t)$ has the derivative $\frac{dg}{dt}=\vec \nabla f(\vec r(t))\cdot\frac{d\vec r}{dt}$. We now compute $$\begin{align*} f(B)-f(A) &= f(\vec r(b))-f(\vec r(a))&\text{($A$ and $B$ are the end points of the curve)}\\ &= g(b)-g(a)&\text{(recall $g(t) = f(\vec r(t))$}\\ &= \int_a^b \frac{dg}{dt}dt&\text{(the fundamental theorem of calculus)}\\ &= \int_a^b \vec \nabla f(\vec r(t))\cdot \frac{d\vec r}{dt} dt&\text{(using the chain rule to compute $\frac{dg}{dt}$)}\\ &= \int_C \vec F\cdot d\vec r&\text{(recall that $\vec \nabla f=\vec F$)}. \end{align*}$$ This shows that the work done by $\vec F$ along $C$ is the difference in the potential $f$.

Suppose that $\vec F$ is a vector field that has a potential $f$ along a curve with differentiable parametrization $\vec r$ for $a\leq t\leq b$. Let $A = \vec r(a)$ and $B=\vec r(b)$ be the endpoints of the curve. Then we have $$\int_C \vec F\cdot d\vec r = \int_C \vec \nabla f \cdot d\vec r = f(B)-f(A).$$

Let's try using this theorem in a few situations.

- Let $\vec F(x,y) = (2x+y,x+4y)$ and $C$ be the parabolic path $\vec r(t) = (t,9-t^2)$ for $-3\leq t\leq 2$.

- Use the work formula we developed earlier in the semester, so $\int_C Mdx+Ndy$ or $\int_C \vec F\cdot d\vec r$, to set up and compute the work done by $\vec F$ along $\vec r$. This is a review of a previous learning target. Feel free to use software to complete the integral.

- Find a potential $f$ for $\vec F$, state $A$ and $B$, and then compute $f(B)-f(A)$.

- Identify the function $g(t) = f(\vec r(t))$, compute $\frac{dg}{dt}$, state $\vec F(\vec r(t))$ and $\frac{d\vec r}{dt}$, and then verify that $\frac{dg}{dt} = \vec F(\vec r(t))\cdot \frac{d\vec r}{dt}$ (these were the terms that appeared in the proof of the fundamental theorem of line integrals).

- Let $\vec F(x,y,z) = (2x+yz,2z+xz,2y+xy)$ and $C$ be the straight segment from $(2,-5,0)$ to $(1,2,3)$. Compute the work done by $\vec F$ along $C$ by first finding a potential for $\vec F$.

- Let $\vec F = (x,2yz,y^2)$. Let $C$ be the curve which starts at $(1,0,0)$ and follows a helical path $(\cos t, \sin t, t)$ to $(1,0,2\pi)$ and then follows a straight line path to $(2,4,3)$. Find the work done by $\vec F$ to get from $(1,0,0)$ to $(2,4,3)$ along this path.

- Suppose a vector field $\vec F$ has a potential. Compute $\int_C \vec F\cdot d\vec r$ where $C$ is the path parametrized by $\vec r(t) = (3\cos t, 3\sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 2\pi$.

Task 5

We need to gain some familiarity with the notation related to gradients, divergence, and curl. As you work on the tasks below, you are welcome to use subscript notation (such as $f_x$ and $M_y$) to simplify writing.

- Suppose $f(x,y,z)$ is twice continuously differentiable.

- Compute the curl of the gradient of $f$, so compute $\vec \nabla \times \vec \nabla f$. Simplify the result as much as possible.

- If a vector field $\vec F = (M,N,P)$ has a potential, then what is the curl of $\vec F$?

- Suppose $\vec F(x,y,z) = (M,N,P)$ is a vector field and $f(x,y,z)$ is a function, both of which are twice continuously differentiable.

- Compute the divergence of the curl of $\vec F$, so compute $\vec \nabla \cdot \left(\vec \nabla \times \vec F\right)$, and simplify the result as much as possible.

- Compute the divergence of the gradient of $f$, so compute $\vec \nabla \cdot \vec \nabla f$, and simplify the result as much as possible.

Task 6

Given a parametric surface, such as $\vec r(u,v) = (u\cos v, u\sin v, v)$ for $2\leq u\leq 4$ and $0\leq v\leq 2\pi$, we can compute the partial derivatives $\vec r_u = \frac{\partial \vec r}{\partial u}$ and $\vec r_v = \frac{\partial \vec r}{\partial v}$, both of which are 3D vectors. Their cross product $\vec n = \vec r_u\times \vec r_v = \dfrac{\partial \vec r}{\partial u}\times \dfrac{\partial \vec r}{\partial v}$ is a vector that is orthogonal to both partial derivatives. The Mathematica code below creates a Module which plots the surface, along with $\vec r_u$, $\vec r_v$, and $\vec n$, using the colors red, blue, and green, respectively.

Module[{r, u, v, ru, rv, n, uBounds, vBounds},

r[u_, v_] := {u Cos[v], u Sin[v], v};

uBounds = {u, 2, 4};

vBounds = {v, 0, 2 Pi};

ru[u_, v_] := Derivative[1, 0][r][u, v];

rv[u_, v_] := Derivative[0, 1][r][u, v];

n[u_, v_] := Cross[ru[u, v], rv[u, v]];

Manipulate[Show[

ParametricPlot3D[r[u, v], uBounds, vBounds, PlotStyle -> Opacity[0.5]],

Graphics3D[{Thick,

Red, Arrow[{r[u1, v1], r[u1, v1] + ru[u1, v1]}],

Blue, Arrow[{r[u1, v1], r[u1, v1] + rv[u1, v1]}],

Green, Arrow[{r[u1, v1], r[u1, v1] + n[u1, v1]}]}],

PlotRange -> All],

{{u1, (uBounds[[2]] + uBounds[[3]])/2}, uBounds[[2]], uBounds[[3]]},

{{v1, (vBounds[[2]] + vBounds[[3]])/2}, vBounds[[2]], vBounds[[3]]}]]

When you run the code above, you'll see two sliders (created using the Manipulate[] command) which allow you to pick the parameter values $(u_1,v_1)$ at which all three vectors are shown.

- How do you interpret the vectors $\vec r_u$, $\vec r_v$, and $\vec n$? How do they physically relate to the surface?

- Run the code above on your own computer. After playing with the sliders a bit, write down an interpretation.

- Let's swap to a different surface. In the code above, change the parametric surface and bounds (lines 2-4) to the following. Run the code and you should see a donut (torus). Play with the sliders again. Does your interpretation of the vectors $\vec r_u$, $\vec r_v$, and $\vec n$ change any, or does this help confirm your interpretation?

r[u_, v_] := {(2 - Cos[u]) Cos[v], (2 - Cos[u]) Sin[v], Sin[u]}; uBounds = {u, 0, 2 Pi}; vBounds = {v, 0, 2 Pi}; - Here are more surfaces to explore. Rerun the code with some of these surfaces, and update your interpretation as needed. If you present in class, then you'll only need to share one of the surfaces you chose to work with (from above, or below).

r[u_, v_] := {u, v, 4 - u^2 - v^2}; uBounds = {u, -2, 2}; vBounds = {v, -2, 2}; r[u_, v_] := {u Cos[v], u Sin[v], 4 - u^2}; uBounds = {u, 0, 2}; vBounds = {v, 0, 2 Pi}; r[u_, v_] := {u Cos[v], u, u Sin[v]}; uBounds = {u, 0, 2}; vBounds = {v, 0, 2 Pi}; r[u_, v_] := {2 Sin[u] Cos[v], 3 Sin[u] Sin[v], 5 Cos[u]}; uBounds = {u, 0, Pi}; vBounds = {v, 0, 2 Pi}; r[u_, v_] := {2 Cos[v], u, 2 Sin[v]}; uBounds = {u, -2, 5}; vBounds = {v, 0, 2 Pi};

The two partial derivatives appear in the differential $d\vec r = \vec r_u du+\vec r_v dv$. The vectors $\vec r_u$ and $\vec r_v$ form the edges of a parallelogram, as do the vectors $\vec r_u du$ and $\vec r_v dv$. The Mathematica code below shows the surface (a torus) and partial derivatives at a chosen point $(u_1,v_1)$. The parallelogram whose edges are $\vec r_u$ and $\vec r_v$ is shaded green, and the parallelogram whose edges are $\vec r_u du$ and $\vec r_v dv$ is shaded black. You can easily change the surface to any of the other surfaces above, by adjusting lines 2-4 of the code.

Module[{r, u, v, ru, rv, n, uBounds, vBounds},

r[u_, v_] := {(2 - Cos[u]) Cos[v], (2 - Cos[u]) Sin[v], Sin[u]};

uBounds = {u, 0, 2 Pi};

vBounds = {v, 0, 2 Pi};

ru[u_, v_] := Derivative[1, 0][r][u, v];

rv[u_, v_] := Derivative[0, 1][r][u, v];

n[u_, v_] := Cross[ru[u, v], rv[u, v]];

Manipulate[Show[

ParametricPlot3D[r[u, v], uBounds, vBounds, PlotStyle -> Opacity[0.5]],

Graphics3D[{Thick,

Red, Arrow[{r[u1, v1], r[u1, v1] + ru[u1, v1]}],

Blue, Arrow[{r[u1, v1], r[u1, v1] + rv[u1, v1]}],

Opacity[0.5], Green, Polygon[{r[u1, v1], r[u1, v1] + ru[u1, v1], r[u1, v1] + ru[u1, v1] + rv[u1, v1], r[u1, v1] + rv[u1, v1]}],

Opacity[1], Black, Polygon[{r[u1, v1], r[u1, v1] + ru[u1, v1] du, r[u1, v1] + ru[u1, v1] du + rv[u1, v1] dv, r[u1, v1] + rv[u1, v1] dv}]}],

PlotRange -> All, ImageSize -> Large],

{{u1, (uBounds[[2]] + uBounds[[3]])/2}, uBounds[[2]], uBounds[[3]]},

{{v1, (vBounds[[2]] + vBounds[[3]])/2}, vBounds[[2]], vBounds[[3]]},

{{du, 0.5}, 0, 1},

{{dv, 0.5}, 0, 1}

]]

When you run the code above, you will find 4 sliders. The first two allow you to pick a point on the surface by choosing values for the parameters $u$ and $v$. The other two allow you to pick values for $du$ and $dv$.

- For a parametric surface $\vec r(u,v)$ with $a\leq u\leq b$ and $c\leq v\leq d$, explain why the surface area is given by $$S=\iint_S dS = \int_{a}^{b}\int_{c}^{d}|\vec r_u\times \vec r_v|dvdu.$$ The items below may help you do this.

- How do you find the area of the green parallelogram?

- How do you find the area of the black parallelogram?

- Explain why $|\vec r_u du \times \vec r_v dv|=|\vec r_u \times \vec r_v |dudv$ (did you notice this was the area of the black parallelogram?).

- Explain why a little bit of surface area is given by $dS = |\vec r_u \times \vec r_v |dudv$.

- To get total surface area, what should we do with the little surface areas $dS$?

- For the surface $\vec r(u,v) = (u\cos v, u\sin v, v)$ for $2\leq u\leq 4$ and $0\leq v\leq 2\pi$, compute the surface area using the formula above.

Task 7

When you can use a potential to compute work, it greatly simplifies things.

- As you complete each problem below, first ask if there is a potential.

- Compute the work done by the vector field $\vec F(x,y) = (y,x)$ on a object that moves along the path $\vec r(t) = (\cos t, \sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 2 \pi$.

- Compute the work done by the vector field $\vec F(x,y) = (-y,x)$ on a object that moves along the path $\vec r(t) = (\cos t, \sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 2 \pi$.

- For each vector field above, use Mathematica to construct an image that shows the vector field along with the curve in the same plot. (You'll need VectorPlot[] and ParametricPlot[], with Show[] to get them in the same plot).

We've seen that if a vector field has a potential, then the derivative is symmetric. Is the converse of this statement true, namely if the derivative of a vector field is symmetric, then does that mean the vector field has a potential?

- Consider the vector field $\ds\vec F(x,y) = \left(\frac{-y}{x^2+y^2},\frac{x}{x^2+y^2}\right)$.

- Show that the derivative is symmetric.

- Compute the work done by the vector field $\vec F(x,y)$ on a object that moves along the path $\vec r(t) = (\cos t, \sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 2 \pi$.

- Explain why $\vec F(x,y)$ does not have a potential.

- Look up "simply connected region" (see section 6.3), and explain why the domain of $\ds\vec F(x,y) = \left(\frac{-y}{x^2+y^2},\frac{x}{x^2+y^2}\right)$ is NOT simply connected.

When the domain of a continuously differentiable vector field is simply connected, then the vector field has a potential if and only if the derivative is symmetric. The concept of a simply connected domain is the start of an entire branch of mathematics called algebraic topology, all stemming from the question, "under what circumstances can we guarantee that a vector field will have a potential?"

Task 8

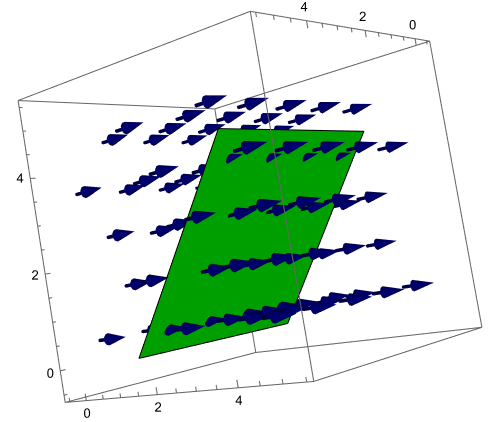

Imagine that the vector field $\vec F(x,y,z)$ represents the velocity of some fluid at point $(x,y,z)$. Let $S$ be a surface (you could think of water flowing through a fish net) through which the fluid will flow. The flux of $\vec F$ across $S$ is the rate at which the fluid flows through the surface.

- In the pictures above, the velocity is given by $\vec F = (0,2,0)$ meters per second and the green surface $S$ is a square with surface area 25 square meters. For each picture above, let's determine the flux of $\vec F$ across $S$.

- Explain why the flow rate of $\vec F$ through $S$ for the first image above is 50 cubic meters per second.

- Explain why the flow rate of $\vec F$ through $S$ for the second image above is 0 cubic meters per second.

- In the third image, the edges of the parallelogram are given by $\vec u = (5,0,0)$ and $\vec v = (0,3,4)$. Compute the flow rate of $\vec F$ through $S$.

In our computations above, we were not concerned about which direction the fluid flowed through the surface. In general, we'll keep track of which direction a fluid flows through a surface, and count flux as negative when the fluid flows the opposite direction. To do this, we pick a unit vector $\hat n$ to the surface, called an orientation of $S$, and decide flux is positive precisely when the vector component of $\vec F$ that is parallel to $\hat n$ is in the same direction as $\hat n$.

- In the third image above, a normal vector to the surface is $\vec u\times \vec v = (5,0,0)\times (0,3,4) = (0,20,-15)$, which means we can use $\hat n = \frac{\vec u\times \vec v}{|\vec u\times \vec v|} = \frac{1}{5}(0,4,-3)$ as an orientation for $S$. Show that the flux of $\vec F$ across $S$ with the orientation $\hat n$ is $ ( \vec F\cdot \hat n)( \text{Surface Area of $S$ } )$.

The computations above generalize rapidly to provide a method for computing the flux of a vector field $\vec F$ across a surface $S$ in the direction of $\hat n$. For a vector field $\vec F$ and surface $S$ with orientation $\hat n$, we have used $dS$ to represent small bits of surface area. This means a small amount of flux across $S$ is given by $d\text{Flux} = \vec F\cdot \hat n dS$. Summing these, and computing a limit provides the flux as $$\text{Flux}=\Phi =\iint_S d\text{Flux} = \iint_S \vec F\cdot \hat n dS.$$ Note that because $\hat n$ is a unit normal vector to $S$, then given a parametrization $\vec r(u,v)$ of $S$ for $(u,v)$ in some region $R$, we know $\hat n = \pm \frac{\vec r_u\times \vec r_v}{|\vec r_u\times \vec r_v|} $ while $dS = |\vec r_u\times \vec r_v|dudv$. This means we can simplify the flux integral above to $$\text{Flux}=\Phi = \iint_R \vec F \cdot (\pm\vec r_u\times \vec r_v)dudv,$$ where the $\pm$ sign must be determined based on the orientation of the surface (something the user must determine).

- Let $\vec F = (x^2 + y, y - z, 3 x + 2 z)$ and $S$ be the surface parametrized by $\vec r(u,v) = (3 \cos v,u,3\sin v)$ for $1\leq u\leq 5$ and $0\leq v\leq 2\pi$. Let $\hat n$ be the unit normal to $S$ which points outwards, away from the $y$-axis. Compute the outward flux $\Phi$ of $\vec F$ across $S$. The steps below can serve as a guide.

- Compute $\vec r_u$ and $\vec r_v$.

- Compute a normal vector $\vec N = \vec r_u \times \vec r_v$, and decide if $\vec N$ points in the same, or opposite direction, as the orientation $\hat n$. This may require you to draw the surface to visually make that determination.

- Insert all the known values into $\iint_R \vec F\cdot (\pm\vec r_u\times \vec r_v)dudv$, making sure all variables have been written in terms of $u$ and $v$. Then use software to compute the integral. (I got $72\pi$.)

- Let $\vec F = (2 y z, x + 3 y, -z^2)$ and $S$ be the surface parametrized by $\vec r(u,v) = (u \cos v, u \sin v, 9 - u^2)$ for $0\leq u\leq 3$ and $0\leq v\leq 2\pi$. Compute the upward ($\hat n$ has positive $z$-component) flux $\Phi$ of $\vec F$ across $S$ in the direction of $\hat n$. The steps above are still the same guide. (I got $-243\pi/2$.)

Task 9

When a vector has no potential, there is a generalization of the fundamental theorem of calculus that can simplify work computations. To discuss this version (called Green's theorem), we first need a few definitions.

When a curve $C$ is a closed curve (starts and ends at the same point), we call the work done by vector field $\vec F$ along $C$ the circulation of $\vec F$ along $C$.

A simple closed curve is a closed curve that does not cross itself.

Let $\vec F(x,y)=\left<M,N\right>$ be a continuously differentiable vector field. At the point $(x,y)$ in the plane, create a circle $C_a$ of radius $a$ centered at $(x,y)$, oriented counterclockwise. The area inside of $C_a$ is $A_a=\pi a^2$. The quotient $\ds \frac{1}{A_a}\oint_{C_a} \vec F \cdot d\vec r$ is a circulation per area. The counterclockwise circulation density of $\vec F$ at $(x,y)$ we define to be $$\lim_{a\to 0} \frac{1}{A_a}\oint_{C_a} \vec F \cdot d\vec r = \lim_{a\to 0} \frac{1}{A_a}\oint_{C_a} Mdx+Ndy =\frac{\partial N}{\partial x}-\frac{\partial M}{\partial y}=N_x-M_y.$$

In the definition above, we could have replaced the circle $C_a$ with a square of side lengths $a$ centered at $(x,y)$ with interior area $A_a$. Alternately, we could have chosen any collection of curves $C_a$ which "shrink nicely" to $(x,y)$ and have area $A_a$ inside. Regardless of which curves you chose, it can be shown that $$N_x-M_y=\lim_{a\to 0} \frac{1}{A_a}\oint_{C_a} Mdx+Ndy.$$

To understand what the circulation density mean in a physical sense, think of $\vec F$ as the velocity field of some fluid (a liquid or gas). The circulation density tells us the rate at which the vector field $\vec F$ causes objects to rotate around points. If circulation density is positive, then particles near $(x,y)$ would tend to circulate around the point in a counterclockwise direction. The larger the circulation density, the faster the rotation. The velocity field of a fluid could have some regions where the fluid is swirling clockwise, and some regions where the fluid is swirling counterclockwise.

We are now ready to state Green's Theorem. Ask me in class to give an informal proof as to why this theorem is valid.

Let $\vec F(x,y)=(M,N)$ be a continuously differentiable vector field, which is defined on an open region in the plane that contains a simple closed curve $C$ and the region $R$ inside the curve $C$. Then we can compute the counterclockwise circulation of $\vec F$ along $C$ using $$ \oint_{C} M dx+Ndy=\iint_R N_x-M_y dA %\quad \text{ and } \quad %\oint_{C} \vec F \cdot \vec n ds=\iint_R M_x+N_y dA. $$

Let's use this theorem to find circulation (work on a closed curve).

- Consider the vector field $\vec F=(2x+3y,4x+5y)$.

- Start by computing $N_x-M_y$.

- If $C$ is the boundary of the rectangle $2\leq x\leq 7$ and $0\leq y\leq 3$, find the circulation of $\vec F$ along $C$. [Doing this without Green's theorem requires we parametrize 4 line segments, compute 4 integrals, and then sum the results. Green's theorem can make this really fast. ]

- Let $R$ be the region inside a circle of radius 3 that is centered at the origin. Compute the work done by $\vec F$ to move an object once, counterclockwise, around this circle. (In other words, compute the circulation of $\vec F$ along $C$ - use Green's theorem to make this fast.)

- Consider the vector field $\vec F=(x^2+y^2,3x+5y)$.

- Start by computing $N_x-M_y$.

- If $C$ is the circle $x^2+y^2=4$ (oriented counterclockwise), then find the circulation of $\vec F$ along $C$.

- Let $R$ be the rectangular region with bounds $0\leq x\leq 4$ and $0\leq y\leq 6$. Compute the counterclockwise circulation of $\vec F$ along the boundary of $R$.

Task 10

Two important vector fields show up over and over again when studying gravity and electrostatics. In this task we will develop a common formula for these fields, show that these fields have a potential, and then practice using the fundamental theorem of line integrals to perform work computations, using the potential.

- We need a formula for a vector field where at each point in space, the vector points towards the origin with a magnitude that proportional to 1 over the square of the distance to the origin. To obtain this field, complete the following steps.

- Let $P=(x,y,z)$ be a point in space. At the point $P$, let $\vec F_1(x,y,z)$ be the vector which points from $P$ to the origin. Give a formula for $\vec F_1(x,y,z)$.

- Give an equation of the vector field where at each point $P$ in space, the vector $\vec F_2(P)$ is a unit vector that points towards the origin.

- Give an equation of the vector field where at each point $P$ in space, the vector $\vec F_3(P)$ is a vector of length 7 that points towards the origin.

- Give an equation of the vector field where at each point $P$ in space, the vector $\vec F(P)$ points towards the origin, and has a magnitude equal to $G/d^2$ where $d = \sqrt{x^2+y^2+z^2}$ is the distance to the origin, and $G$ is a constant.

- The gravitational vector field is directly related to the radial field $\ds\vec F(x,y,z) = \frac{\left(-x,-y,-z\right)}{(x^2+y^2+z^2)^{3/2}}$.

- We say that a vector field is conservative when the work done by the field is independent of the path traveled. Show that this vector field is conservative, by finding a potential for $\vec F$.

- Compute the work done by $\vec F$ to move an object from $(1,2,-2)$ to $(0,-3,4)$ along ANY path that avoids the origin.

Task 11

This task focuses on exploring the curl and divergence of a vector field, using Mathematica, to gain some geometric intuition about what these vectors compute.

- For each vector field below, compute the curl of the vector field, modify this chunk of Mathematica code to visualize the vector field and the curl, and look for relationships between $\vec F$ and $\vec\nabla \times \vec F$.

F[x_, y_, z_] := {-y, x, 0} Show[VectorPlot3D[Evaluate[F[x, y, z]], {x, -1, 1}, {y, -1, 1}, {z, -1, 1}, VectorAspectRatio -> 1/8], VectorPlot3D[Evaluate[Curl[F[x, y, z], {x, y, z}]], {x, -1, 1}, {y, -1, 1}, {z, -1, 1}, VectorPoints -> Coarse, VectorAspectRatio -> 1/4]]- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (-y,x,0)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (-y,x,0)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (-z, 0, 2 x)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (2x, 3y, 4z)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (0, 3 z, -4 y)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (-z, z, x - y)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (y - z, -x + z, x - y)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (y^2, -x, 0)$

- Pick your own vector field.

- Summarize what relationships, if any, you saw.

- For each vector field below, compute the divergence of the vector field, modify this chunk of Mathematica code to visualize the vector field, and look for relationships between $\vec F$ and $\vec\nabla \cdot \vec F$.

F[x_, y_, z_] := {2 x, 0, 0} VectorPlot3D[Evaluate[F[x, y, z]], {x, -1, 1}, {y, -1, 1}, {z, -1, 1}]- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (2x,0,0)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (0,-3y,0)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (0,0,4z)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (2x,-3y,4z)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (x,y,z)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (-y,x,0)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z) = (x^2,0,0)$

- Pick your own vector field.

- Summarize what relationships, if any, you saw.

Task 12

We've seen all the new notation that we'll encounter for the rest of the semester. This task has us practice using the notation we've learned.

- Consider the vector field $\vec F = (x,x-z,y+z)$, the surface $S$ parametrized by $\vec r(u,v)=(u^2, u\cos v, u\sin v)$ for $0\leq u\leq 2$ and $0\leq v\leq 2\pi$, and the curve $C$ parametrized by $\vec r(t) = (4,2\cos t, 2\sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 2\pi$.

- Draw the surface $S$ and curve $C$. How are these two objects related?

- Compute $\vec N = \vec r_u\times \vec r_v$ and determine if $\vec N$ points inward toward the $x$-axis, or outwards away from the $x$-axis.

- Set up and compute the integral $\ds \int_C Mdx+Ndy+Pdz$, computing the work done by $\vec F$ along $C$.

- Set up and compute $\ds \iint_S \vec \nabla \times \vec F\cdot \hat n dS$, computing the flux of the curl of $\vec F$ across $S$ in the direction $\hat n$ outwards away from the $y$-axis.

- Consider the vector field $\vec F = (x,x-z,y+z)$, the solid domain $D$ that lies inside the sphere $x^2+y^2+z^2=25$, and the surface $S$ parametrized by $\vec r(u,v)=(5\sin v\cos u, 5 \sin v \sin u, 5 \cos v)$ for $0\leq u\leq 2\pi$ and $0\leq v\leq \pi$.

- Draw the surface $S$ and domain $D$. How are these two objects related?

- Compute $\vec N = \vec r_u\times \vec r_v$ and determine if $\vec N$ points inward toward the domain $D$ or outwards away from the domain $D$.

- Set up and compute $\ds \iint_S \vec F\cdot \hat n dS$ for $\hat n$ pointing outwards, away from the solid inside $S$. This computes the outward flux of $\vec F$ across $S$.

- Set up and compute $\ds \iiint_D \vec \nabla \cdot \vec F dV$, the triple integral of the divergence of $\vec F$ over the domain $D$.

Task 13

What do the curl and divergence of a vector field compute? How do we physically interpret them?

- Head to the following webpages and read their descriptions.

- After reading the 4 pages above, head to Wikipedia's article on magnetic fields, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magnetic_field. Skim through the article (you do not need to read and comprehend all of it).

- Are there any new symbols you don't recognize? What are they?

- Search for the word "divergence" in the text, and read the paragraph(s) where you find it.

- Search for the word "curl" in the text, and read the paragraph(s) where you find it.

- Come with questions about anything you would like to discuss.

Task 14

As we proceed through the remainder of this unit, we'll find that three types of integrals appear quite often.

- Work integrals: $\ds\int_{C} Mdx+Ndy+Pdz$

- Surface integrals: $\ds \iint_S f(x,y,z) dS$

- Flux integrals: $\ds \iint_S \vec F \cdot \hat n dS$

For each type of integral above, use Mathematica to create a code chunk that you can use to compute each type of integral. This will allow you free yourself from performing tedious computations, letting you focus on bigger picture ideas.

- For the work integral, you can pick the vector field $\vec F(x,y,z)$, parametrization $\vec r(t)$, and bounds for $t$.

- For the surface integral, you can pick the surface $S$, function $f(x,y,z)$, parametriztion $\vec r(u,v)$, and bounds for $u$ and $v$.

- For the flux integral, you can pick the surface $S$, orientation $\hat n$, parametriztion $\vec r(u,v)$, and bounds for $u$ and $v$.

The ReplaceAll[] command in Mathematica will allow you to replace any instance of $x$, $y$, or $z$ with the corresponding value from your parametrization. Alternately, you can use @ and @@ for function composition (@ when the input is a number, while @@ when the input is a vector). This allows you to enter the vector field using Cartesian coordinates. Other commands you'll find useful are D[], Cross[], Norm[], Dot[], and Integrate[].

As an example, to dot the vector field $\vec F = (3x+4yz, 2y^2, x-4z)$ with the derivative of the parametrization $\vec r(t) = (3\cos t, 3\sin t, 4 t)$, and then make sure everything is in terms of $t$, we can use the following code.

ClearAll[F, r, x, y, z, t]

F[x_, y_, z_] = {3 x + 4 y z, 2 y^2, x - 4 z}

r[t_] = {3 Cos[t], 3 Sin[t], 4 t}

Dot[F @@ r[t], D[r[t], t]]

(*Or using short cut notation (.for Dot and/. for ReplaceAll)*)

F @@ r[t] . D[r[t], t]

Task 15

Green's theorem connects circulation along a simple closed curve in 2D to an integral along the region inside the curve. The circulation per area (circulation density) is given by $N_x-M_y$ for a 2D vector field. A similar fact is true in 3D, namely if $S$ is a surface with a simple closed curve $C$ that forms the boundary of $S$, then the circulation along $C$ can be computed instead by summing circulation densities (circulation per surface area) along the surface. Given a point $(x,y,z)$ and a unit vector $\hat n$, we calculate the circulation density of $\vec F$ about $\hat n$ at $(x,y,z)$ in a similar manner, as follows.

- We construct a circle $C_a$ of radius $a$ in the plane through $(x,y,z)$ with normal vector $\hat n$.

- We compute the counter-clockwise circulation about $\hat n$, obtaining $\oint_{C_a} Mdx+Ndy+Pdz$.

- We divide by the area $A_a$ inside $C_a$, to obtain a circulation per area.

- The circulation density of $\vec F$ about $\hat n$ at $(x,y,z)$ is the limit $$\lim_{a\to 0}\frac{1}{A_a}\oint_{C_a} Mdx+Ndy+Pdz = \vec \nabla \times \vec F \cdot \hat n.$$

The curl of a vector field provides information about circulation density in every direction (just dot by the direction about which you want to know how things are rotating). Note that for a 2D vector field, we can use the normal vector $\hat n = (0,0,1)$, and then we see that the circulation density for a vector field in 2D is $$(N_z-P_y, P_x-M_z, N_x-M_y) \cdot (0,0,1) = N_x-M_y.$$

We're now ready to state Stokes's theorem.

Given an orientable differentiable parametric surface with unit normal vector (orientation) $\hat n$ and piecewise smooth boundary $\partial S$, where each portion of the boundary is oriented compatibly with $\hat n$ (see below for meaning), then the flux of the curl of $\vec F=(M,N,P)$ is equal to the circulation of $\vec F$ along $\partial S$, which we can write as $$\iint_S \vec \nabla \times \vec F \cdot \hat n dS = \int_{\partial S} Mdx+Ndy+Pdz.$$

- We use $\partial S$ to stand for the boundary of $S$. We are not taking partial derivatives of the surface, rather it's a notation convention.

- Note that $\partial S$ might consist of multiple curves, which may or may not be connected to each other. Sum $\int_{C} Mdx+Ndy+Pdz$ for each curve $C$ that is part of the boundary to compute $\int_{\partial S} Mdx+Ndy+Pdz$.

- We say that a curve $C$ is oriented compatibly with $\hat n$ provided that the surface is on the left side of $C$ when viewing the surface from the side designated by $\hat n$. As you wrap your right hand about the vector $\hat n$, your hand should be moving in the same direction as the orientation on $C$.

Let's verify this theorem in some examples.

- Let $\vec F(x,y,z) = (x+2y, 3x-4z, 2z)$. Consider the surface $S$ parametrized by $\vec r(u,v) = (u\cos v, u\sin v, u^2)$ for $0\leq u\leq 3$ and $0\leq v\leq 2\pi$ with orientation $\hat n$ pointing away from the $z$-axis. The boundary $\partial S$ consists of a single curve $C_1$ parametrized by $\vec r_1(t) = (3\cos t, 3\sin t, 9)$ for $0\leq t\leq 2\pi$.

- Draw the surface and curve. Do your best to explain what it means for $\hat n$ and the curve to be oriented compatibly.

- Set up and compute the surface integral $\ds \iint_S \vec \nabla \times \vec F \cdot \hat n dS$.

- Set up and compute the line integral $\ds \int_{\partial S} Mdx+Ndy+Pdz$. Do you get the same result as the surface integral?

- Let $\vec F(x,y,z) = (x+2y, 2x+4z, 4y)$. Consider the plane in the first octant with the three vertices $(3,0,0)$, $(0,3,0)$ and $(0,0,3)$. An equation of the plane is $x+y+z=3$, which we can parameterize using $\vec r(u,v) = (u,v,3-u-v)$ for $0\leq u\leq 3$ and $0\leq v\leq 3-u$. The boundary $\partial S$ consists of 3 curves, which we can parameterize using $$\begin{align*}

\vec r_1(t) &= (3-3t,3t,0) \quad \text{for} 0\leq t\leq 1,\\

\vec r_2(t) &= (0,3-3t,3t) \quad \text{for} 0\leq t\leq 1,\\

\vec r_3(t) &= (3t,0,3-3t) \quad \text{for} 0\leq t\leq 1.

\end{align*}$$

- Draw the surface and 3 curves, placing an arrow on the curves to demonstrate the direction of motion.

- Compute $\ds \int_{\partial S} Mdx+Ndy+Pdz$ by computing the three line integrals and summing the result.

- Compute $\ds \iint_S \vec \nabla \times \vec F \cdot \hat n dS$, using an orientation $\hat n$ that is compatible with the orientation of the curves.

Task 16

We've discussed circulation density and connected it to the curl of a vector field. Let's construct a corresponding analog for flux.

Given a point $(x,y,z)$, we calculate the flux density of $\vec F$ at $(x,y,z)$ as follows.

- We construct a sphere $S_a$ of radius $a$ centered at $(x,y,z)$.

- We compute the outward flux of $\vec F$ across the surface of the sphere, so $\iint_{S_a} \vec F\cdot\hat n dS$.

- We divide by the volume $V_a$ inside $S_a$, to obtain a flux per volume.

- The flux density of $\vec F$ at $(x,y,z)$ is the limit $$\lim_{a\to 0}\frac{1}{V_a}\iint_{S_a}\vec F\cdot\hat n dS = \vec \nabla \cdot \vec F.$$

The divergence of a vector field provides the flux density.

We are now ready to state the divergence theorem.

Given a solid domain $D$ with piecewise smooth boundary $\partial D$, where each portion of the boundary is a surface oriented pointing outwards away from $D$, then the integral of the divergence of $\vec F=(M,N,P)$ along $D$ is equal to the outward flux of $\vec F$ across the boundary $\partial D$, which we can write as $$\iiint_D \vec \nabla \cdot \vec F dV = \iint_{\partial D}\vec F\cdot\hat n dS.$$

- Note that $\partial D$ might consist of multiple surfaces. Sum $\iint_{S}\vec F\cdot\hat n dS$ for each surface $S$ that is part of the boundary to compute $\iint_{\partial D}\vec F\cdot\hat n dS$.

- For every surface $S$ that is part of the boundary, remember to make sure $\hat n$ is the outward pointing unit vector, pointing away from the solid domain $D$.

Let's verify this theorem in some examples.

- Consider the vector field $\vec F = (x^2, 2 y, x + y + z)$ and sphere of radius 5. We can parameterize the surface $S$ using $\vec r(u,v) = (5 \cos(u)\sin(v),5\sin(u)\sin(v),5\cos(v))$ for $0\leq u\leq 2\pi$ and $0\leq v\leq \pi$. The solid domain $D$ satisfies $\rho\leq 5$ (using spherical coordinates - you'll need appropriate bounds for $\theta$ and $\phi$). Set up and compute both $\iiint_D \vec \nabla \cdot \vec F dV$ and $\iint_{\partial D}\vec F\cdot\hat n dS$, using the outward pointing normal vector $\hat n$. (I got $500\pi$ for both. Pay attention to the direction in which $\vec r_u\times \vec r_v$ points.)

- Consider the vector field $\vec F = (5x,x-z,y+z+1)$ and solid domain $D$ in space that lies below the paraboloid $z=1-r^2$ (using cylindrical coordinates) and above the $xy$-plane. The boundary of $D$ consists of two surfaces. The top surface is parametrized by $\vec r(u,v) = (u \cos v,u \sin v,1-u^2)$ for $0\leq u\leq 1$ and $0\leq v\leq 2\pi$. The bottom surface is the plane $z=0$, and for this particular problem we can parameterize it using $\vec r(u,v) = (u\cos v,u\sin v,0)$ for $0\leq u\leq 1$ and $0\leq v\leq 2\pi$. Set up and compute both $\iiint_D \vec \nabla \cdot \vec F dV$ and $\iint_{\partial D}\vec F\cdot\hat n dS$, using the outward pointing normal vector $\hat n$. (I got $3\pi$ for both. The flux integral across the top surface is $4\pi$, and across the bottom surface is $-\pi$.)

Task 17

For a surface $S$ with parametrization $\vec r(u,v) = (x(u,v),y(u,v),z(u,v))$ for $(u,v)$ in some region $R$, we have shown that surface area is $$S = \iint_S dS = \iint_R |\vec r_u\times\vec r_v|dudv.$$ This means we can compute mass, average values, centroids, centers-of-mass, etc, in a manner similar to what we have already done.

- For a function $f$ defined at points on the surface, the average value is $$\bar f = \frac{\iint_S f dS}{\iint_S dS} = \frac{\iint_R f(u,v) |\vec r_u\times\vec r_v| dudv}{\iint_R |\vec r_u\times\vec r_v| dudv}.$$ Replacing $f$ with $x$, $y$, or $z$ obtains the corresponding coordinate of the centroid of the surface.

- Given a density $\delta$ at points on the surface, the mass of the surface is $$ m = \iint_S dm = \iint_S \delta dS = \iint_R \delta(u,v) |\vec r_u\times\vec r_v| dudv.$$ The center-of-mass is given by $(\bar x, \bar y, \bar z) = \frac{\iint_S (x,y,z) \delta dS}{\iint_S \delta dS}$ which we can write as $$\begin{align*} \bar x &= \frac{\iint_R x(u,v) \delta(u,v) |\vec r_u\times\vec r_v| dudv}{\iint_R \delta(u,v) |\vec r_u\times\vec r_v| dudv},\\ \bar y &= \frac{\iint_R y(u,v) \delta(u,v) |\vec r_u\times\vec r_v| dudv}{\iint_R \delta(u,v) |\vec r_u\times\vec r_v| dudv},\\ \bar z &= \frac{\iint_R z(u,v) \delta(u,v) |\vec r_u\times\vec r_v| dudv}{\iint_R \delta(u,v) |\vec r_u\times\vec r_v| dudv}. \end{align*}$$

Note that there are lots of things going on with each integral. Software will greatly reduce the amount of time needed to set up and compute these integrals. The commands that will be most useful are ParametricPlot3D[], D[], Cross[], Norm[], and Integrate[].

- Consider the surface $\vec r(u,v) = (3\cos v,3\sin v, u)$ for $1\leq u\leq 5$ and $0\leq v\leq \pi$. Start by drawing the surface. From your picture, state $\bar x$ and $\bar z$. Then set up and compute an integral formula that gives the $y$-coordinate of the centroid.

- A satellite dish lies along the parametric surface $\vec r(u,v) = (u^2, u\cos v, u\sin v)$ for $0\leq u\leq 2$ and $0\leq v\leq 2\pi$. Start by drawing the surface. The temperature at points on and near the dish is given by $T(x,y,z) = x+z$. Set up and compute an integral formula that gives the average temperature of the satellite dish.

- The top half of the surface $S$ of a donut (a torus) can be parametrized by $\vec r(u,v) = ((5 - 3 \cos u) \cos v, (5 - 3 \cos u) \sin v, 3 \sin u)$ for $0\leq u\leq \pi$ and $0\leq v\leq 2\pi$. Imagine that someone puts icing on the top of this donut (so creates a surface), but the thickness of the icing is more on the top of the donut than on the sides. While not a perfect way to model this situation, we could use $\delta = kz$ for some constant $k$ as a way to model the surface with varying density. Show that the center-of-mass of the surface $S$ with density function $\delta = kz$ is $(\bar x, \bar y, \bar z) = (0,0,\frac{3\pi}{4})$.

Task 18

Stokes's theorem can be applied when the boundary of a surface consists of disjoint curves. Remember to check if the parametrization associated with each curve is compatible with the orientation on the surface. When not compatible, a simple negative sign can quickly fix any issues.

Let $\vec F = (2x-3y,x^2+2z,4xy)$.

- Consider the surface $S$ parametrized by $\vec r(u,v) = (u\cos v, u, u \sin v)$ for $1\leq u\leq 3$ and $0\leq v\leq 2\pi$, oriented by $\hat n$ pointing away from the $y$-axis. The boundary $\partial S$ of $S$ is the union of the two disconnected curves $C_1$ with parametrization $\vec r_1(t) = (\cos t, 1, \sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 2\pi$ and $C_2$ with parametrization $\vec r_2(t) = (3\cos t, 3, 3\sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 2\pi$. Provided the curves are oriented compatibly with $\hat n$, Stokes's theorem states that $$\ds \int_{\partial S} Mdx+Ndy+Pdz = \iint_S \vec \nabla \times \vec F \cdot \hat n dS.$$

- Draw the surface and curves.

- Compute $\ds \iint_S \vec \nabla \times \vec F \cdot \hat n dS$. (I got $104\pi$.)

- Compute $\ds \int_{C_1} Mdx+Ndy+Pdz$ and $\ds \int_{C_2} Mdx+Ndy+Pdz$, using the parametrizations provided.

- Explain how to combine the results of the previous computations to obtain $\ds \int_{\partial S} Mdx+Ndy+Pdz$.

- Now instead let $S$ be half of the surface above, parametrized by $\vec r(u,v) = (u\cos v, u, u \sin v)$ for $1\leq u\leq 3$ and $0\leq v\leq \pi$. The boundary of $S$ now consists of 4 connected curves, two arcs and two straight lines. One arc has parametrization $\vec r_1(t) = (\cos t, 1, \sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq \pi$. One of the straight lines has parametrization $\vec r_2(t) = (t, t, 0)$ for $1\leq t\leq 3$.

- Compute $\ds \iint_S \vec \nabla \times \vec F \cdot \hat n dS$ (change the bounds of what you did in the previous part).

- Give parametrizations for the other two curves that make up $\partial S$.

- Compute $\ds \int_{C} Mdx+Ndy+Pdz$ for each of the 4 curves in $\partial S$. (You'll end up with $6+2\pi$, $54+54\pi$, $14/3$, and $86/3$, all of which could be negative instead of positive, based on your parametrization.)

- Explain how to combine the results of the previous computations to obtain $\ds \int_{\partial S} Mdx+Ndy+Pdz$.

Task 19

Consider the vector field $\vec F = \frac{ (x,y,z) }{ (x^2+y^2+z^2) ^{3/2}}$. This vector field is directly proportional to gravitational and electric fields. In this task, we will show that flux of this field across any closed surface that contains the origin is $4\pi$, while the flux across any surface that does not contain the origin is zero.

- Show that the divergence of $\vec F$ is 0, provided $(x,y,z)\neq(0,0,0)$. You can to this by hand, or with software, or find the solution somewhere online (one of the links in task 13 has the work).

- Consider the surface $S$ which is a sphere of radius $a$ (so $x^2+y^2+z^2=a^2$). Compute the outward flux of $\vec F$ across $S$, and show that you get $$\Phi = \iint_S \vec F\cdot \hat n dS = 4\pi.$$ In particular, notice that the answer does not depend on the radius of the sphere. There are multiple ways to do this. One option is to obtain a parametrization of the surface (look back at previous problems to get a parametrization) and then set up and compute the integral directly. Another is to reason out geometrically what $\hat n$ must equal because we're on a sphere of radius $a$, and then replace $x^2+y^2+z^2$ with $a^2$ in many places.

- Let $S$ be any closed surface which does not contain $(0,0,0)$ on the surface, or inside the surface. Explain why $\iint_S \vec F\cdot \hat n dS =0$

- Let $S$ be any closed surface which does contain $(0,0,0)$ inside the surface. Explain why $\iint_S \vec F\cdot \hat n dS =4\pi$. (Start by picking a small radius $a$ so that the sphere $x^2+y^2+z^2=a^2$ lies entirely inside $S$.)

Task 20

Let $D$ be the solid region in space that lies above the cone $z^2=x^2+y^2$ and below the paraboloid $z=6-x^2-y^2$. In cylindrical coordinates, the domain $D$ lies above the cone $z=r$ and below the paraboloid $z=6-r^2$. Let $\vec F = (x^2, 4y+z, z-x+3)$. Verify the divergence theorem for this solid region. A parametrization for the cone is $\vec r(u,v) = (u\cos v, u\sin v, u)$ for $0\leq u\leq 2$ and $0\leq v\leq 2\pi$. A parametrization for the parabaloid is $\vec r(u,v) = (u\cos v, u\sin v, 6-u^2)$ for $0\leq u\leq 2$ and $0\leq v\leq 2\pi$.

- Compute $\iint_S \vec F\cdot \hat n dS$ across the cone, making sure you have an outward pointing normal vector.

- Compute $\iint_S \vec F\cdot \hat n dS$ across the paraboloid, making sure you have an outward pointing normal vector.

- Compute $\iiint_D \vec \nabla \cdot \vec F dV$, and show how to combine the results of the previous computations to get the same value.

In my work above, I ended up seeing the values $-20\pi/3$, $60\pi$, and $160\pi/3$.