Task 1

Start by looking up the terms vector-valued function and vector parameterization of a curve.

- Write definitions in your own words for the terms above.

- For each vector parameterization below, construct a graph of the curve. [Hint: make a table of points if needed, including $t$, $x$, and $y$, and then just plot the $(x,y)$ coordinates).

- $\vec r(t) = \left< 2t+1, 4-3t\right>$ for $0\leq t\leq 2$.

- $(x,y) = (\cos t, \sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 3\pi/2$.

- $(x,y)(t) = (\sin t, \cos t)$ for $0\leq t\leq \pi$.

- $\langle x,y,z\rangle = (2\cos t, 2\sin t, t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 4\pi$.

If you do not have a working installation of Mathematica, please download and install Mathematica. We'll be using Mathematica throughout the semester, and it will be the only technology tool you are allowed to use on quizzes. If you've never used it before, don't worry. At this point you'll only need to know how to enter input and evaluate code, which is covered in the first example of this Fast Introduction For Math Students, provided by Wolfram.

- Use the Mathematica commands ParametricPlot[] and ParametricPlot3D[] to check your work above, and then plot the parametric curve given by $\vec r(t) = (t+\sin t, t\cos t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 6\pi$. The following code will plot the second curve above.

ParametricPlot[{Cos[t], Sin[t]}, {t, 0, 3 Pi/2}]

Task 2

Start by locating (1) a definition of the dot product of two vectors, (2) what it means for two vectors to be orthogonal, and (3) the dot product form of the law of cosines.

- Compute the dot product of the two vectors $\vec a = 3\vec i-4\vec j+2\vec k$ and $\vec b = (-1,3,6)$.

- Find the angle between $\vec a$ and $\vec b$.

- Give a value $k$ so that the vectors $\vec a = 3\vec i-4\vec j+2\vec k$ and $\vec c = \langle 2, -1, k\rangle$ are orthogonal.

- A car is moving in the direction $\vec v = (-5,7)$. The car makes a 90 degree turn to the left. Give a vector that is parallel to this new direction of motion.

- Run the following code in Mathematica, and then explains in words what this code is doing.

Solve[Dot[{3, 4, c}, {11, c, 7}] == 0, c] - The law of cosines is often written as $c^2=a^2+b^2-2ab\cos \theta$, where $\theta$ is the angle opposite the side with length $c$.

- Given two vectors $\vec u$ and $\vec v$ above, use the law of cosines to explain why $$|\vec u||\vec v| \cos \theta = \frac{|\vec u|^2+|\vec v|^2-|\vec u-\vec v|^2}{2}.$$

- Letting $\vec u = (u_1,u_2,u_3)$ and $\vec v = (v_1,v_2,v_3)$, simplify the right hand side of the above equation to show that $|\vec u||\vec v| \cos \theta = u_1v_1+u_2v_2+u_3v_3$.

Task 3

Start by looking up the definition of a unit vector. Consider the two points $P = (1, 2, 3)$ and $Q = (2, −1, 0)$.

- Write the vector $\vec {PQ} $ in component form $(a, b, c)$.

- Find the length, or magnitude, of the vector $\vec {PQ} $.

- Find a unit vector in the same direction as $\vec {PQ} $.

- Find a vector of length 7 units that points in the same direction as $\vec {PQ} $.

- Search for a Mathematica command that will compute the magnitude of a vector for you. Use that command to verify your computation for $|\vec{PQ}|$.

Self Check

I'll occasionally add relevant problems from OpenStax. As needed, spend a few minutes working on some exercises below. If you get stuck on a prep task, feel free to bring a solution to one of the textbook exercises to share.

- In section 1.1, complete checkpoints 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3. Use the corresponding examples, if needed, to help you.

- In section 2.3, complete an exercise for each group in 123-144, and then try a few problems in 149-154.

Task 4

Suppose for a short time that a rover follows a path given by $(x, y) = (1t + 3, −2t + 4)$. This is the same as writing $(x, y) = (1, −2)t + (3, 4)$.

- Construct a plot that shows the location of the rover at time $t = 0, 1, 2$, and add some arrows as well as a line to illustrate the rover’s path. Use Mathematica's ParametricPlot[] command to draw this path.

- What is the speed of the rover? (you may assume that distances are in meters, and time is in minutes).

- What is the rover's velocity (hint, this should be a vector)?

- When we write the path in the form $(x, y) = (1, −2)t + (3, 4)$, what do the quantities $(1, −2)$ and $(3, 4)$ have to do with the path?

- The rover is no longer on flat ground, rather is sitting at point $P = (0, 2, 3)$. It starts to climb in the direction $\vec v = \langle 1, −1, 2\rangle$.

- Write a vector equation $(x, y, z) = (?, ?, ?)$ for the line that passes through the point $P$ and is parallel to $\vec v$. Use Mathematica's ParametricPlot3D[] command to draw this path. Feel free to use $0\leq t\leq 1$ for the time bounds.

- Generalize your work to give an equation of the line that passes through the point $P = (x_1 , y_1 , z_1)$ and is parallel to the vector $\vec v = (v_1 , v_2 , v_3 )$.

Task 5

Suppose the Curiosity rover travels in a circular path given by the parametric curve $\vec r(t) = (3 \cos t, 3 \sin t)$.

- Graph the curve $\vec r$ (you should obtain a circle) and make sure you designate the direction in which the rover is traveling. Use Mathematica's ParametricPlot[] command to verify you've got the right path (you must use capital letters for function names, so type Cos[t] for $\cos t$).

- Compute both $\ds \frac{d \vec r}{dt}$ and $\ds\frac{d^2\vec r}{dt^2}$.

- The command below will define the function $r$ and compute the first derivative of $\vec r(t)$ for you. Try modifying the command to compute the second derivative.

r[t_] := {3 Cos[t], 3 Sin[t]} r'[t]

- The command below will define the function $r$ and compute the first derivative of $\vec r(t)$ for you. Try modifying the command to compute the second derivative.

- Locate the point on your graph that the rover is at when $t = \pi/2$. How would you describe the velocity and acceleration of the rover at this point? Compute both $\frac{d\vec r}{dt}(\frac{\pi}{2})$ and $\frac{d^2\vec r}{dt^2}(\frac{\pi}{2})$, and confirm that these vectors do indeed provide the acceleration and velocity of the rover at $t = \pi/2$.

- Swap to the time $t = \pi/4$. On your graph, draw the vectors $\frac{d\vec r}{dt}(\frac{\pi}{4})$ and $\frac{d^2\vec r}{dt^2}(\frac{\pi}{4})$ with their tail placed on the curve at $\vec r(\frac{\pi}{4})$. These vectors are the velocity and acceleration.

- Check your work with Mathematica. For example, after running the commands above you can type r'[Pi/4].

- Give a vector equation of the tangent line to this curve at $t = \pi/4$. (You have a point and a direction vector. How do you use them?)

Task 6

Suppose a heavy box needs to be lowered down a ramp. The box exerts a downward force of say 200 Newtons (gravity), which we could write in vector notation as $\vec F=\left<0,-200\right>$. If the ramp was placed so that the box needed to be moved right 6 m, and down 3 m, then we'd need to get from the origin $(0,0)$ to the point $(6,-3)$. This displacement can be written as $\vec d=\left<6,-3\right>$. The force $\vec F$ acts straight down, rather than parallel to the displacement. Find out how much of the force $\vec F$ acts in the direction of the displacement. We are going to break the force $\vec F$ into two components, one component in the direction of $\vec d$, and another component orthogonal to $\vec d$. The component of the force that is parallel to $\vec d$ is useful in understanding energy computations. The component of the force that is orthogonal to $\vec d$ is useful in understanding surface friction.

We want to write $\vec F$ as the sum of two vectors $\vec F = \vec w+\vec n$, where $\vec w$ is parallel to $\vec d$ and $\vec n$ is orthogonal to $\vec d$. Since $\vec w$ is parallel to $\vec d$, we can write $\vec w=c\vec d$ for some unknown scalar $c$. This means that $\vec F=c\vec d+\vec n$.

- Start by drawing a picture that shows how $\vec F$, $\vec d$, $\vec w$, and $\vec n$ are related.

- Use the fact that $\vec n$ is orthogonal to $\vec d$ to show that $\ds c = \frac{\vec F\cdot \vec d}{\vec d\cdot \vec d}$. [Hint: Dot each side of $\vec F=c\vec d+\vec n$ with $\vec d$ and distribute. You'll need to use the fact that $\vec n$ and $\vec d$ are orthogonal to remove $\vec n\cdot \vec d$ from the problem.]

- Now that we have a formula for $c$, use that formula to show that $\vec w = c\vec d = (80,-40)$. We call this the projection of $\vec F$ onto $\vec d$ (or the component of $\vec F$ that is parallel to $\vec d$), and write $$\text{proj}_{\vec d}\vec F = \vec F_{\parallel \vec d}= \left(\frac{\vec F\cdot \vec d}{\vec d\cdot \vec d}\right)\vec d.$$

- Obtain a formula for $\vec n$, the component of the force that is orthogonal to $\vec d$. This is sometimes written as $\vec F_{\perp \vec d}$.

- In your own words, how do you interpret $\vec w$ and $\vec n$?

The following Mathematica code draws all the vectors above. which you can use to check how you're doing.

orig = {0, 0}

F = {0, -200}

d = {6, -3}

proj = Projection[F, d]

Graphics[{

Arrow[{orig, F}],

Arrow[{orig, d}],

Red, Arrow[{orig, proj}],

Green, Arrow[{proj, F}],

Green, Dashed, Arrow[{orig, F - proj}],

Red, Dashed, Arrow[{F - proj, F}]

}]

Self Check

I'll occasionally add relevant problems from OpenStax. As needed, spend a few minutes working on some exercises below. If you get stuck on a prep task, feel free to bring a solution to one of the textbook exercises to share.

- Equations of lines: Section 2.5, checkpoint 2.43 and exercises 243 - 250.

- Derivatives of Vector Valued functions: Section 3.2, checkpoint 3.5 and exercises 41-54.

- Projection practice: section 2.3, checkpoint 2.27 and exercises 167-172

Task 7

Consider the curve $\vec r(t) = (2t+3, 4(2t-1)^2)$.

- Construct a graph of $\vec r$ for $0\leq t\leq 2$.

- If this curve represents the path of a rover (meters for distance, minutes for time), find the velocity of the rover at any time $t$, and then specifically at $t=1$. What is the rover's speed at $t=1$?

- Give a vector equation of the tangent line to $\vec r$ at $t=1$. Include this on your graph.

- Mathematica's Show[] command will plot multiple curves on the same axes. In the code chunk below, add the vector equation of the tangent and bounds for $t$ to visually confirm that the equation you obtained is indeed an equation of the tangent line.

Show[ ParametricPlot[{2 t + 3, 4 (2 t - 1)^2}, {t, 0, 2}], ParametricPlot[?] ] - State the rover's acceleration vector.

- Explain how to obtain the slope of the tangent line, and then write an equation of the tangent line using point-slope form. [Hint: How can you turn the direction vector, which involves $(dx/dt)$ and $(dy/dt)$, into the number given by the slope $(dy/dx)$?]

Task 8

We are ready to tackle the problem of finding the length of a path. This length we call arc length. If a rover moves at a constant speed, then the distance traveled is simply $$\text{distance} = \text{speed}\times\text{time}.$$ This requires that the speed be constant. What if the speed is not constant? Over a really small time interval $dt$, the speed is almost constant (provided we make an assumption), so we can still use the idea above.

Suppose a rover (or other object) moves along the path given by $\vec r(t)=(x(t),y(t))$ for $a\leq t\leq b$. We know that the velocity is $\dfrac{d\vec r}{dt}$, and so the speed is just the magnitude of this vector.

- Show that we can write the rover's speed at any time $t$ as $$\ds\sqrt{\left(\frac{dx}{dt}\right)^2+\left(\frac{dy}{dt}\right)^2}.$$

- If the rover moves at speed $\ds\sqrt{\left(\frac{dx}{dt}\right)^2+\left(\frac{dy}{dt}\right)^2}$ for a little time length $dt$, what's the little distance $ds$ that the rover traveled?

- Explain (Riemann sums may help) why the length of the path given by $\vec r(t)$ for $a\leq t\leq b$ is $$s=\int ds=\int_a^b \left|\frac{d\vec r}{dt}\right| dt=\int_a^b \sqrt{\left(\frac{dx}{dt}\right)^2+\left(\frac{dy}{dt}\right)^2}dt.$$

- The path $\vec r(t) = (3\cos t, 3\sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq 2\pi$ is a circle of radius 3. Verify that the formula above does in fact yield the circumference of this circle.

- If the curve is in space (so $\vec r(t)=(x(t),y(t),z(t))$ is the path), then how does the arc length formula above change?

- What assumptions must we make about the parametrization $\vec r$ so that the formula above is valid?

Task 9

Gravity is often the first example we encounter of a vector field. Other important vector fields arise when we study magnetism, electricity, fluid flow, and more. To analyze how a river flows, we can construct a plot of the river and at each point in the river we draw a vector that represents the velocity at that point. This creates a collection of many vectors drawn all at once, where the base of each velocity vector is placed at the point where the velocity occurs. For gravity, a similar picture can be drawn, though all the vectors will point down with the same magnitude. This task has us construct a plot of a vector field.

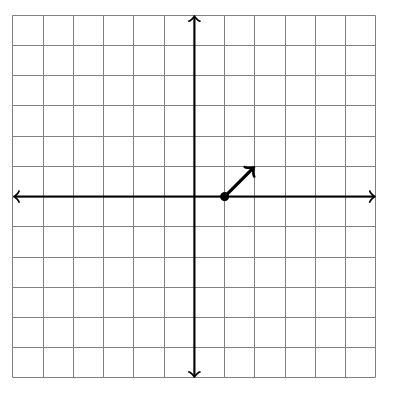

Consider the function $\vec F(x,y) = \left<x-2y,x+y\right>$. This is a function where the input is a point $(x,y)$ in the plane, and the output is the vector $\left<x-2y,x+y\right>$, were the first component is the function $M(x,y) = x-2y$ and the second component is the function $N(x,y) = x+y$. For example, if we input the point $(1,0)$, then the output is $\left<1-2(0),1+0\right> = \left<1,1\right>$. To construct a vector field plot, we draw the vector $\left<1,1\right>$ with its base located at the input $(1,0)$. In the picture below, based at $(1,0)$ we draw a vector that points right 1 and up 1.

- Complete the table below and add the other 7 vectors to the graph.

\(\begin{array}{c|c} (x,y)&\left<x-2y,x+y\right>\\\hline (1,0)&\left<1,1\right>\\ (1,1)&\\ (1,-1)&\\ (0,1)&\\ (0,-1)&\\ (-1,0)&\\ (-1,1)&\\ (-1,-1)& \end{array}\)

- Repeat the above for the vector field $\vec F(x,y)=(-2y,3x)$, constructing a vector field plot consisting of 8 vectors. Can you think of an application that this vector field might help model or explain?

- Constructing plots, by hand, of vector fields can be quite time consuming. Software will rapidly create them for us. The biggest hurdle is that a vectors get really long, and as more vectors are added, there will be a lot of overlap. One way to deal with this complexity is to instead just draw vectors that point in the correct direction, and then use color to help understand which vectors are longer, and which vectors are shorter. Mathematica's VectorPlot[] command does precisely this. After running the code chunk below, adapt it show a plot of the second vector field.

VectorPlot[{x - 2 y, x + y}, {x, -2, 2}, {y, -2, 2}]- Create your own examples of vector fields (you get to pick the functions $M$ and $N$ to put inside $(M,N)$), and plot them using Mathematica.

The distinction in notation between using parenthesis for points $(x,y)$ and angle brackets for vectors $\left<M,N\right>$ is useful for a first introduction to vector field plots. However, using parenthesis for both is quite common and how we'll designate vector field in the future, letting the reader realize from context whether something is a point or a vector.

The Mathematica code chunk below creates a vector field plot that does NOT rescale the arrows, using the 25 points $(x,y)$ with integer coordinates where $x$ and $y$ are between -2 and 2. Notice that with more arrows, overlap will become a problem.

F[x_, y_] := {x - 2 y, x + y}

myArrows = Table[Table[

Arrow[{{x, y}, {x, y} + F[x, y]}],

{x, -2, 2}], {y, -2, 2}] // Flatten;

Graphics[myArrows, Axes -> True]

Self Check

I'll occasionally add relevant problems from OpenStax. As needed, spend a few minutes working on some exercises below. If you get stuck on a prep task, feel free to bring a solution to one of the textbook exercises to share.

- section 3.2: checkpoint 3.7, exercises 75-92

- Arc Length Practice: section 3.3: checkpoint 3.9, exercises 102-112

Task 10

Work is a transfer of energy. When a force acts through a displacement, work is done. Gravity acts on falling objects, transferring potential energy to kinetic energy. Any force, when acting through a displacement, will result in work being done.

- When a constant force and displacement are in the same straight line direction, the work done is simply the product of the magnitude of the force, and the distance.

- When a constant force acts opposite a straight line displacement, the work is the negative of the magnitude of the force and the distance.

If a constant force is not parallel (or antiparallel) to a straight line displacement $\vec d$, then we instead use the component of the force that is parallel to the displacement (so $\vec F_{\parallel \vec d}$) to compute work.

- Let $\vec F=(-1,2)$ and $\vec d=(3,4)$.

- Start by computing $\vec F_{\parallel d} = \text{proj}_{\vec d}\vec F$ and $\vec F_{\perp d}$.

- Construct a picture that shows the relationship between $\vec F,$ $\vec d$, $\text{proj}_{\vec d}\vec F$, and $\vec F_{\perp d}$. Try doing this by hand first, and then feel free to use the Mathematica code from a previous problem to verify that you're doing this correctly.

- Compute the work done by $\vec F$ through the displacement $\vec d$ by computing $|\vec F_{\parallel d}|$ and $|\vec d|$. Should the work be positive or negative?

- Change the force to $\vec F = (-2,0)$. but keep $\vec d=(3,4)$.

- Construct a similar picture as above, showing the relationship between $\vec F,$ $\vec d$, $\text{proj}_{\vec d}\vec F$, and $\vec F_{\perp d}$. Feel free to construct this picture with, or without, doing any computations.

- Compute the work done by $\vec F$ through the displacment $\vec d$. Should the work be positive or negative?

- Can you find a simpler way to compute the work done by $\vec F$ through $\vec d$ than computing $|\vec F_{\parallel d}|$ and $|\vec d|$?

- Use Mathematica to redo the computations for this entire task. The commands that may be most useful are Dot[], Projection[], and Norm[]. This will help you (1) become more comfortable using Mathematica and (2) help increase your confidence when learning new things.

Task 11

- Find the length of the curve $\ds \vec r(t) = \left(t^3,\frac{3t^2}{2}\right)$ for $t\in[1,3]$. The notation $t\in[1,3]$ means $1\leq t\leq 3$. Be prepared to show us your integration steps in class (you'll need a substitution).

- Now find the length of the helix $\vec r(t) = (2\cos t, 2\sin t, t)$ for $t\in [0, 4\pi] $.

- Use Mathematica to compute both integrals above, and verify that you have the correct value.

- Challenge: Write a block of code that starts by entering the function, and the bounds for the integral, and then performs all the needed computations for obtaining arc length. Here's the first two lines (it's possible to finish this block of code with one more line).

r[t_] := {t^3, 3 t^2/2} tB = {t, 1, 3}

Task 12

As you complete this task, remember to check your computations with Mathematica, bolstering your confidence that you're mastering these new ideas.

Suppose a rover is currently moving and has a velocity vector $\vec v = (3,4)$. A force acts on the rover causing an acceleration of $\vec a = (-1,5)$. The rover is currently at the location $(2,-3)$.

- Draw picture that shows the rover's location along with the velocity and acceleration vectors drawn with their base at the rover's location.

- Find the vector component of the acceleration that is parallel to the velocity (so find $\vec a_{\parallel \vec v}$), and then find the vector component of the acceleration that is orthogonal to the velocity (so find $\vec a_{\perp \vec v}$).

- Will this acceleration cause the rover to speed up or slow down? Explain.

- Will this acceleration cause the rover to turn left or right? Explain.

A probe above Mars is currently moving and has a velocity vector $\vec v = (-2,1,2)$. The onboard thrusters apply a force that causes an acceleration of $\vec a = (0,2,-3)$.

- Find both $\vec a_{\parallel \vec v}$ and $\vec a_{\perp \vec v}$.

- Will this acceleration cause the satellite to speed up or slow down? Explain.

- How would you interpret $\vec a_{\perp \vec v}$?

Self Check

I'll occasionally add relevant problems from OpenStax. As needed, spend a few minutes working on some exercises below. If you get stuck on a prep task, feel free to bring a solution to one of the textbook exercises to share.

- Work: section 2.3, checkpoint 2.29 and exercises 175-179

- Projection: section 2.3, checkpoint 2.27 and exercises 167-172

- Arc Length: section 3.3: checkpoint 3.9, exercises 102-112

Task 13

We can generalize what we've done to find the work done by a force (which doesn't have to be constant) acting on an object, along a (possibly non straight) path. Recall that work is a transfer of energy. Consider the following examples:

- A tornado picks up a couch and applies forces to the couch as it swirls around the center. Work is the transfer of the energy from the tornado to the couch, giving the couch its kinetic energy.

- When an object falls, gravity does work on the object. The work done by gravity converts potential energy to kinetic energy.

- If we consider the flow of water down a river, it is gravity that gives the water its kinetic energy. We can place a hydroelectric dam next to a river to capture a lot of this kinetic energy. Work transfers the kinetic energy of the river to rotational energy of the turbine, which eventually ends up as electrical energy available in our homes.

When we study work, we are really studying how energy is transferred. This is one of the key components of modern life. Recall that the work done by a constant vector field $\vec F$ through a straight line displacement $\vec d$ is the dot product $\vec F\cdot \vec d$.

- When an object moves from $A=(6,0)$ to $B=(0,3)$ encountering the constant force $\vec F = (2,5)$, the work is done by $\vec F$ as the object moves from $A$ to $B$ is simply the displacement $B-A=(-6,3)$ dotted by the force, so we have $W = \vec F\cdot \vec d = (2,5)\cdot(-6,3) = -12+15=3$.

An object moves from $A=(6,0)$ to $B=(0,4)$. A parametrization of the object's path is $\vec r(t) = (-3,2)t+(6,0)$ for $0\leq t\leq 2$.

- For $0\leq t\leq 1$, the force encountered is $\vec F = (2,5)$ and the object moves from $\vec r(0)= (6,0)$ to $\vec r(1) = (3,2)$. How much work is done in the first second?

- For $1\leq t\leq 2$, the force encountered is instead $(2,7)$. How much work is done in the last second?

- How much total work is done?

- If we encounter a constant force $\vec F$ over a little displacement $d\vec r$, explain why the little work done is $\ds dW = \vec F\cdot d\vec r =\vec F\cdot \frac{d\vec r}{dt}dt $.

- Suppose that the force constantly changes as we move along the curve. At $t$, we encountered the force $\vec F(t) = (2,5+2t)$, which we could think of as the wind blowing stronger and stronger to the north. Explain why the total work done by this force along the path is $$\ds W=\int_C \vec F\cdot d\vec r = \int_0^2 (2,5+2t)\cdot (-3,2)dt.$$ Then compute this integral and show you get 16.

- If you are familiar with the units of energy, complete the following. What are the units of $\vec F$, $d\vec r$, and $dW$.

If a force of magnitude $F$ acts through a displacement with magnitude $d$, then the most basic definition of work is $W=Fd$, the product of the force and the displacement. Recall that this basic definition has a few assumptions.

- The force $F$ must act in the same direction as the displacement.

- The force $F$ must be constant throughout the displacement.

- The displacement must be in a straight line.

The dot product lets us remove the first assumption as work is $W=\vec F\cdot \vec r,$ where $\vec F$ is a force acting through a displacement $\vec r$. We just saw we can remove the assumption that $\vec F$ is constant to obtain $$W=\int_C \vec F \cdot d\vec r = \int_a^b F\cdot \frac{d\vec r}{dt}dt, $$ provided we have a parametrization of $\vec r$ with $a\leq t\leq b$. We now get rid of the assumption that $\vec r$ is a straight line.

- Suppose that we move along the curve $C$ parametrized by $\vec r(t) = (3\cos t,3\sin t)$. As we move along $C$, we encounter a rotational force $\vec F(x,y) = (-2y,2x)$.

- Draw $C$. Then at several points on the curve, draw the vector field $\vec F(x,y)$. For example, at the point $(3,0)$ you should have the vector $\vec F(3,0)=(-2(0),2(3))=(0,6)$, a vector sticking straight up 6 units. Is the curve moving with the vector field, or against the vector field?

- Explain why we can state that a little bit of work done by a force $\vec F$ over a small displacement $d\vec r$ is $dW = \vec F\cdot d\vec r$. Why does it not matter that $\vec r$ does not move in a straight line?

- Since a little work done by $\vec F$ along $d\vec r$ (a small bit of $C$) is $dW = \vec F\cdot d\vec r$, we know that the total work done is $\int_C dW = \int_C \vec F\cdot d\vec r$. This gives us $$W = \int_C\left(-2y,2x\right)\cdot d\vec r = \int_0^{2\pi}\left(-2(3\sin t),2(3\cos t)\right)\cdot(-3\sin t, 3\cos t)dt.$$ Complete the integral, showing that the work done by $\vec F$ along $C$ is $36\pi$.

$$W = \int_C \vec F\cdot d\vec r= \int_a^b \vec F(\vec r(t))\cdot \frac{d\vec r}{dt}dt.$$ Note that we put the $C$ under the integral $\int_C$ to remind us that we are integrating along the curve $C$. This means we need to get a parametrization of the curve $C$, and give bounds before we can integrate with respect to $t$.

If we let $\vec F = (M,N)$ and we let $\vec r(t)=(x,y)$, so that $d\vec r = (dx,dy)$, then we can write work in the differential form $$W = \int_C \vec F\cdot d\vec r= \int_C (M,N)\cdot (dx,dy) = \int_C Mdx+Ndy.$$

Task 14

Suppose an object travels along the path given by $\vec r(t) = (3t,-2t^2)$. The velocity is $\vec v(t) = (3,-4t)$ and the acceleration is $\vec a(t)=(0,-4)$.

- Is there a time $t$ at which the velocity and acceleration vectors are parallel? Explain.

- Compute the vector component of the acceleration vector that is parallel to the velocity vector. In other words, compute $\text{proj}_{\vec v}\vec a$. We'll call this vector $\vec a_{\parallel \vec v}$.

- What is the vector component of the acceleration vector that is orthogonal to the velocity vector? We'll call this vector $\vec a_{\perp \vec v}$.

- Draw a picture that shows the relationship among $\vec v$, $\vec a$, $\vec a_{\parallel \vec v}$, and $\vec a_{\perp \vec v}$.

Task 15

- Write a block of code in Mathematica that will draw and compute the arc length of any parameterized curve.

- Test your block of code on a curve where we've already computed the arc length, so something like $\ds \vec r(t) = \left(t^3,\frac{3t^2}{2}\right)$ for $1\leq t\leq 3$.

- Copy the block of code that you created and change the interval of integration to $2\leq t\leq 5$. Check that the plot and arc length update appropriately.

- Now use your code above to examine arc length for a few other curves. For each curve below, set up an integral formula (on paper) which would give the length. Then use your block of code to sketch the curve and compute the arc length. Do not worry about integrating them by hand (they will get ugly really fast, and some will return interesting results in Mathematica).

- The parabola $\vec r(t) = (t,t^2)$ for $t\in[0,3]$.

- The ellipse $\vec r(t) = (4\cos t,5\sin t)$ for $t\in[0,2\pi]$.

- The hyperbola $\vec r(t) = (\tan t,\sec t)$ for $t\in[-\pi/ 4,\pi/4]$.

Self Check

I'll occasionally add relevant problems from OpenStax. As needed, spend a few minutes working on some exercises below. If you get stuck on a prep task, feel free to bring a solution to one of the textbook exercises to share.

- Work on paths (line integrals): section 2.3, checkpoint 6.18, example 6.23 and exercises 49-54

Task 16

Consider the parabolic curve $y=4-x^2$ for $-1\leq x\leq 2$, and the vector field $\vec F(x,y) = (2x+y,-x)$. A parametrization $\vec r(t)$ of this parabolic curve that starts at $(-1,3)$ and ends at $(2,0)$ is $\vec r(t) = (t, 4-t^2)$.

- Compute $d\vec r$ and state $dx$ and $dy$. What are $M$ and $N$ in terms of $t$?

- Compute the work done by $\vec F$ on an object that moves along the parabola from $(-1,3)$ to $(2,0)$ (i.e. compute $\int _C Mdx+Ndy$). Check your work using code at the end of this problem.

- How much work is done by $\vec F$ to move an object along the same parabola from $(2,0)$ to $(-1,3)$. In other words, if you traverse along a path backwards, how much work is done?

- We now want to know how much work is done by the same vector field on an object that moves along a straight line from $(-1,3)$ to $(2,0)$.

- Give a parametrization $\vec r(t)$ of the straight line curve that starts at $(-1,3)$ and ends at $(2,0)$. Make sure you give bounds for $t$.

- Compute $d\vec r$ and state $dx$ and $dy$. What are $M$ and $N$ in terms of $t$?

- Compute the work done by $\vec F$ to move an object along the straight line path from $(-1,3)$ to $(2,0)$.

- Check your work using the code at the end of this problem.

- Optional (we'll can discuss this in class if you don't have it). How much work does it take to go along the closed path that starts at $(2,0)$, follows the parabola $y=4-x^2$ to $(-1,3)$, and then returns to $(2,0)$ along a straight line. Show that this total work is $W=-9$.

Use Software to check your work above.

Here's an example of how to compute the above using SageMath (an open source alternative to Mathematica). Hit evaluate at the bottom. Feel free to modify the code below to fit your needs.

var('t','x','y') #Define your variables

r(t) = (t,4-t^2) #State your parametrization

bounds = (t,-1,2) #Give bounds for the parametrization

F(x,y) = (2*x+y,-x) #State the vector field

xbounds = (x,-1,2) #These bounds are useful if you want to make a good plot.

ybounds = (y,0,4) #These bounds are useful if you want to make a good plot.

dr = r.diff(t) #Compute the derivative

dW=F(*r(t)).dot_product(dr(t)) #Find a little bit of work. The code r[0] gives the first component, and r[1] gives the second.

W=integrate(dW,bounds)

pretty_print(html("""The work done by $F=%s$ along the curve r=$%s$

over the bounds $%s$ is $%s$"""%tuple(map(latex, [F(x,y), r(t), bounds, W]))))

show(table([

[r"$\vec r(t)$", "$(x,y)$", r(t)],

[r"$d\vec r$", "$(dx,dy)$", dr(t)],

["$\vec F(x,y)$", F(x,y), F(*r(t))],

["$M$", F(x,y)[0], F(*r(t))[0]],

["$N$", F(x,y)[1], F(*r(t))[1]],

[r"$dW=\vec F\cdot d\vec r$", "$Mdx+Ndy$", dW],

[r"$W=\int_C \vec F\cdot d\vec r$",W,W]

]

))

p=parametric_plot(r(t),bounds)

p+=plot_vector_field(F,xbounds,ybounds)

show(p)

We can obtain the same results in Mathematica.

r[t_] := {t, 4 - t^2};

tB = {t, -1, 2};

F[x_, y_] := {2 x + y, -x};

xB = {x, -1, 2};

yB = {y, 0, 4};

dr = r'[t]

dW = (F @@ r[t]) . dr

(*The @@ represents function composition when the output of the inside function is a vector.*)

W = Integrate[dW, tB]

Show[

ParametricPlot[r[t], Evaluate[tB]],

VectorPlot[F[x, y], Evaluate[xB, yB], VectorScaling -> Automatic, VectorStyle -> Automatic]

]

With a few optional arguments, we can show only the vectors that lie on the curve. We have to specify where to plot the vectors using the VectorPoints. By default, Mathematica draws the vectors so that their center lies over the point, rather than their base, which we can change with the VectorMarkers option.

numArrows = 20;

a = tB[[2]];

b = tB[[3]];

timeIncrement = (b - a)/(numArrows - 1);

points = Table[r[t], {t, a, b, timeIncrement}];

Show[ParametricPlot[r[t], Evaluate[tB]],

VectorPlot[F[x, y], Evaluate[xB, yB], VectorScaling -> Automatic,

VectorStyle -> Automatic, VectorPoints -> points,

VectorMarkers -> Placed["Arrow", "Start"]]]

Task 17

We have shown that for a parametric curve given by $\vec r(t)$, for $a\leq t\leq b$, the length of the curve is given by $s = \int_a^b \left|\dfrac{d \vec r}{dt}\right|dt$. We can use a different variable for the parameter, say $\tau$, and then for the curve $\vec r(\tau )$, for $0\leq \tau \leq t$ we get the arc length parameter $$s(t) = \int_0^t \left|\dfrac{d \vec r}{d\tau}\right|d\tau.$$ This provides a function $s(t)$ that tells us the arc length traveled along a curve after $t$ units of time. Note that the derivative of $s(t)$ is (why?) $$\frac{ds}{dt} = \frac{d}{dt}\int_0^t \left|\dfrac{d \vec r}{d\tau}\right|d\tau = \left|\dfrac{d \vec r}{dt}\right|,$$ which is just the speed. By requiring that speed be positive on a curve, then the arc length parameter is an increasing function. This is the reason that the definition of a smooth curve requires that a parametrization have a nonzero derivative.

- For the helix $\vec r(t) = (3\cos t, 3\sin t, 4t)$, set up the intergral formula that gives the arc length parameter, and then simplify to show that the arc length parameter is $s(t) = 5t$.

- If you've traveled 20 units along the helix $\vec r(t) = (3\cos t, 3\sin t, 4t)$, how much time has elapsed? In general, if you've traveled $s$ units, how much time has elapsed. You will have written $t$ as a function of the arc length $s$, obtaining the inverse function $t(s)$.

- State the functions $\vec r(t)$ and $\vec r(t(s))$. Then compute both $\dfrac{d\vec r}{dt} = \dfrac{d\vec r(t)}{dt}$ and $\dfrac{d\vec r}{ds}=\dfrac{d\vec r(t(s))}{ds}$.

- Rather than writing $\dfrac{d\vec r}{ds}$ in terms of $s$, it's common to replace $s$ with $s(t)$, giving $\dfrac{d\vec r}{ds}(t)$. Explain why, in general, we have $\dfrac{d\vec r}{ds}(t) = \dfrac{d\vec r/dt}{ds/dt}$.

- For the curve $\vec r(t) = (a\cos t, a\sin t, bt)$, compute both $\dfrac{d\vec r}{dt}$ and $\dfrac{d\vec r}{ds}$.

- Show that the magnitude of $\dfrac{d\vec r}{ds}$ is always 1. We call this the unit tangent vector and write $\vec T = \dfrac{d\vec r}{ds}.$

Task 18

In this task, we'll show that the product rule applies to the dot product, and then use that to prove that if a vector-valued function has constant length, then the derivative of the function is orthogonal to the original function.

- Let $\vec r_1(t) = (f(t), g(t))$ and $\vec r_2(t) = (m(t), n(t))$. Prove that $$\frac{d}{dt}(\vec r_1\cdot \vec r_2) = \frac{d}{dt}(\vec r_1)\cdot \vec r_2+\vec r_1\cdot \frac{d}{dt}(\vec r_2).$$

- Now suppose that $\vec r(t)$ has constant length (meaning $|\vec r(t)|=c$ for some constant $c$). Prove that $\vec r(t) \cdot \dfrac{d\vec r(t)}{dt} = 0$. [Hint, if we know $|\vec r(t)|=c$, what does this mean about $\vec r(t)\cdot \vec r(t)$? How are the dot product and length connected?]

- Draw the curve $\vec r(t) = (4\cos t+2, 4\sin t-1)$. Show that the velocity has constant length and then verify that the derivative of the velocity (so acceleration) is orthogonal to the velocity.

The problem above gets used quite often in engineering applications. If a beam is attached to a system at a single point, then the beam can rotate about the point. Because the length of the beam is constant, then any rotational forces caused by the beam as it impacts other objects will always be normal to the beam.

Task 19

Let $\vec u = (a,b,c)$ and $\vec v = (d,e,f)$. Our goal is to find a single nonzero vector $(x,y,z)$ that is orthogonal to both $\vec u$ and $\vec v$, preferably with as few fractions as possible in the final answer.

- Explain why we need to solve the system of equations $$ax+by+cz=0\quad\text{and}\quad dx+ey+fz=0.$$

- To solve the system above, multiply the first equation by $d$ and the second equation by $-a$ (assume for a moment that both $a$ and $d$ are not zero). Then add the two equations together to eliminate $x$, which will allow you to solve for $y$ in terms of $z$. Finish by solving for $x$ in terms of $z$ (there are many ways to do this). You will have shown that every solution to this system can be written in the form $$(x,y,z) = \left(\left(\frac{bf-ce}{ae-bd}\right)z,\left(\frac{cd-af}{ae-bd}\right)z,z\right). $$

- The above solution has some complicated fractions. Why is $(x,y,z) = (bf-ce, cd-af, ae-bd)$ a solution to the system?

From your work above you will have developed a formula for the cross product of two vectors. The cross product of the two vectors $\vec u = (u_1,u_2,u_3)$ and $\vec v = (v_1,v_2,v_3)$ is the vector $$\vec u\times \vec v = (u_2v_3-u_3v_2, u_3v_1-u_1v_3, u_1v_2-u_2v_1).$$

- Let $\vec u=(1,-2,3)$ and $\vec v=(2,0,-1)$.

- Compute $\vec u\times \vec v$ and $\vec v\times \vec u$. How are they related?

- Compute and simplify both $\vec u \cdot (\vec u\times \vec v)$ and $\vec v \cdot (\vec u\times \vec v)$. Did you get zero for both? What fact about the cross product guarantees you get zero?

Self Check

I'll occasionally add relevant problems from OpenStax. As needed, spend a few minutes working on some exercises below. If you get stuck on a prep task, feel free to bring a solution to one of the textbook exercises to share.

- Arc Length Parameter: section 3.3: checkpoint 3.10, exercises 127-128, 116, 119, 121, 126

- Look at theorem 3.3 in section 3.2. Properties 4 and 7 we completed in a prior task. Prove any of the other properties that seem interesting to you.

- Cross product: section 2.4: checkpoint 2.30, exercises 183-192

Task 20

Given a curve with parametrization $\vec r(t)$, we have already seen that a unit tangent vector is given by $\ds \vec T = \frac{d\vec r}{ds} = \frac{d\vec r/dt}{|d\vec r/dt|}$. Note that this vector has constant length of 1, which means that its derivative, so $\frac{d\vec T}{dt}$, is orthogonal to $\vec T$. This vector describes how the direction of motion changes. The vector $\ds\vec N = \frac{d\vec T/dt}{|d\vec T/dt|}$ provides a unit vector, we call the principle unit normal vector, that describes the direction in which an object is turning. The cross product $\vec B = \vec T\times \vec N$ we call the binormal vector. These three vectors, namely $\vec T$, $\vec N$, and $\vec B$, provide what we call the Frenet or TNB frame, and are commonly used when describing motion.

- For the curve $\vec r(t) = (3\cos t, 3\sin t, 4t)$, compute $\vec T$, $\vec N$, and $\vec B$. Show how you obtained each step in your computations.

- The definitions of $\vec T$ and $\vec N$ both made them one unit long. How long is $\vec B$?

- After computing these by hand, use Mathematica to perform the computations. Using ComplexExpand[] and Simplify[] will help reduce the output. Here's an example of how your code might start (I'll let you add lines for the other vectors. Note that you'll need to use something like Nn for the normal vector, as N already is the Mathematica command for numerically approximating something.)

r[t_] := {3 Cos [t], 3 Sin[t], 4 t} T[t_] := r'[t]/Norm[r'[t]] // ComplexExpand // Simplify T[t] Nn[t_] :=

- For the curve $\vec r(t) = (t,0,t^2)$, compute $\vec T$, $\vec N$, and $\vec B$. Show how you obtained each step in your computations. If things get ugly quite quickly, because of a quotient rule, then you're on the right path. It's OK to stop at some point (spend 10-15 minutes on this), and just use software to finish the computation. Including the command $Assumptions = t \[Element] Reals at the top of your code will help simplify the results greatly.

$Assumptions = t \[Element] Reals r[t_] := {t,0,t^2} T[t_] := r'[t]/Norm[r'[t]] // ComplexExpand // Simplify T[t] Nn[t_] :=

For a visual representation of the Frenet Frame, please visit this Geogebra site. It's possible to create a very similar visual in Mathematica or Python (something you could aim for with a self-directed learning project).

Task 21

Given a parametric curve with parametrization $\vec r(t)$, the curvature vector is the rate of change of the direction of motion with respect to arc length, so $\ds \vec \kappa = \frac{d\vec T}{ds}$. We compute the derivative with respect to arc length so that we obtain a physical property of the curve, rather than a property that relates to how quickly we traverse the curve. The curvature is the magnitude of the curvature vector, so $$\kappa = |\vec \kappa| = \left| \frac{d\vec T}{ds} \right|.$$ The radius of curvature is the quantity $1/\kappa$.

- Explain why $\ds \kappa = \frac{|d\vec T/dt|}{|d\vec r/dt|}$.

- For the circle $\vec r(t) = (5\cos(2t), 5\sin(2t))$, compute the curvature $\kappa$ and radius of curvature $1/\kappa$.

- For the helix $\vec r(t) = (3\cos(t), 3\sin(t),4t)$, compute the curvature and radius of curvature.

- For the parabola $\vec r(t) = (t,t^2)$, at $t=0$ compute the curvature $\kappa(0)$ and radius of curvature. (Once you have taken all needed derivatives, plug in zero before trying to simplify).

- Draw the parabola from the previous part. How would you interpret the radius of curvature at $t=0$ in this context?

- Check your computations above with Mathematica.

Task 22

There are many ways to compute the TNB frame and curvature. In this task, we'll develop a few others.

- Explain why $ \vec N = \dfrac{\vec r^{\prime\prime}_{\perp \vec r^{\prime}}}{ |\vec r^{\prime\prime}_{\perp \vec r^{\prime} }| } $.

- Explain why $ \vec B = \dfrac{\vec r^{\prime}\times \vec r^{\prime\prime}}{|\vec r^{\prime}\times \vec r^{\prime\prime}|}$.

- For a function of the form $\vec r(x) = (x, f(x))$, show that $\kappa = \dfrac{|f''(x)|}{(1+(f'(x))^2)^{3/2}}$.

Self Check

I'll occasionally add relevant problems from OpenStax. As needed, spend a few minutes working on some exercises below. If you get stuck on a prep task, feel free to bring a solution to one of the textbook exercises to share.

- section 3.3 exercises 113-151

Task 23

Let $P=(a,b,c)$ be a point on a plane in 3D. Let $\vec n=(A,B,C)$ be a normal vector to the plane (so the angle between the plane and $\vec n$ is 90$^\circ$). Let $Q=(x,y,z)$ be another point on the plane.

- What is the angle between $\vec {PQ} = (x-a,y-b,z-c)$ and $\vec n=(A,B,C)$?

- Explain why an equation of the plane through $P$ with normal vector $\vec n$ is $$A(x-a)+B(y-b)+C(z-c)=0.$$

- Consider the three points $R=(1,0,0)$, $S=(2,0,-1)$, and $T=(0,1,3)$. Give an equation of the plane which passes through these three points. [You already have a point on the plane. With three points, you can get two vectors that are in the plane. How can you get a vector that is normal to the plane?]

- Draw the plane above in Mathematica, using the ContourPlot3D[] command.

Task 24

Consider the parametric curve $\vec r(t) = (t^2-3t, 4t-5)$ for $0\leq t\leq 3$.

- Draw the curve.

- Compute the velocity and speed at any time $t$.

- Give an equation of tangent line at $t=2$.

- Compute the acceleration at $t=2$.

- At $t=2$, compute the vector component of the acceleration that is parallel to the velocity, and the vector component of the acceleration that is orthogonal to the velocity.

- Set up an integral to compute the arc length of the curve. Then compute the integral (using software is fine).

Task 25

Recall that the curvature vector is $\kappa = \dfrac{d\vec T}{ds}$, with curvature being the length of this vector. This vector tells us how much the direction of motion ($\vec T$) changes, as we increase the distance moved along the curve. As such, a tight corner will result in a large change of direction and hence a large curvature. Large corners will result in a small curvature.

The radius of curvature at a point, namely $1/\kappa$, provides the radius of a circle that approximates the shape of curve at that point. Large turns result in a large radius of curvature, while tight turns results in a small radius of curvature. This circle lies in the plane formed by $\vec T$ and $\vec N$ (so a normal vector to this plane is $\vec B$). We call this plane the osculating plane. The center of the circle can be found by following $\vec N$ from the point on the curve.

- For the curve $\vec r(t) = (3\cos t, 3\sin t, 4t)$, we have already computed $\vec T$, $\vec N$, $\vec B$, and $\kappa$. At $t=\pi/2$, evaluate these quantities.

- Give an equation of the the osculating plane at $t=\pi/2$. You'll need to identify a normal vector to the plane, and a point on the plane.

- Explain why the center of curvature is given by $\vec r + \frac{1}{\kappa}\vec N$.

- Give the location of the center of curvature for $\vec r(t) = (3\cos t, 3\sin t, 4t)$ at $t=\pi/2$.

Task 26

Density is generally a mass per unit volume. However, when talking about a wire, it's simpler to let density be the mass per unit length. We can make objects out of composite materials, where the density is different at different places in the object. For example, we might have a straight wire where one end is copper and the other end is gold. In the middle, the wire slowly transitions from being all copper to all gold. Such composite materials are engineered all the time (though probably not our example wire). The density at point $(x,y,z)$ is given by the quantity $\delta (x,y,z)$.

- Suppose a wire $C$ has the parameterization $\vec r(t)$ for $t\in[a,b]$. Suppose the wire's density (mass per unit length) at a point $(x,y,z)$ on the wire is given by the function $\delta(x,y,z)$. Since density is a mass per length, multiplying density by a small length $ds$ gives us the mass of a small portion of the curve. We represent this symbolically using $dm=\delta(\vec r(t_0)) ds$. Explain why the mass $m$ of the wire is given by the formulas below (explain why each equal sign is true): $$m=\int_C dm = \int_C \delta ds = \int_a^b \delta(\vec r(t)) \left|\frac{d\vec r}{dt}\right|dt.$$

- Now suppose a wire lies along the straight segment from $(0,2,0)$ to $(1,1,3)$. A parametrization of this line is $\vec r(t) = (t,-t+2,3t)$ for $t\in[0,1]$. The wire's density (mass per unit length) at a point $(x,y,z)$ is $\delta(x,y,z)=x+y+z$.

- Is the wire heavier at $(0,2,0)$ or at $(1,1,3)$?

- What is the total mass of the wire? [Replace $x$, $y$, $z$, and $ds$ with what they equal in terms of $t$ and then integrate.]

- Now consider an insulated wire that lies along the curve $\vec r(t) = (7\cos t, 7\sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq \pi$. The wire contains charged particles where the charge per unit length at location $(x,y)$ is given by $q(x,y)=y$. We'll compute the total charge on the wire.

- Draw the curve. Then at several points on the curve write the value of $q(x,y)$ at that point. (Optional: Should the total charge be positive or negative?)

- Why is the little charge $dQ$ over a little distance $ds$ approximately given by $dQ = q(x,y)ds$?

- The total charge is the sum of the charges over all the little pieces on the rod. This gives us the total charge as $$Q_{\text{total}}=\int_CdQ=\int_C q(x,y)ds = \int_a^b y \sqrt{\left(\frac{dx}{dt}\right)^2+\left(\frac{dy}{dt}\right)^2}dt.$$ Replace $x$ and $y$ with what they are in terms of $t$ and then finish by computing the integral above.