Task 1

We need to become adept at describing regions in the plane, using inequalities. For this first task, we'll start with inequalities and from them shade a region in the plane. Draw each by hand first. Then use, or adapt, the provided Mathematica code to check how you did.

- Shade the region in the $xy$-plane that satisfies the inequalities $-1\leq x\leq 1$ and $1-x\leq y\leq 4-x^2$.

(*This version generally works great for 2D regions.*) ParametricPlot[{x, y}, {x, -1, 1}, {y, 1-x, 4 - x^2}] (*This version is generic and generalizes to 3D. It might be slow.*) R = ParametricRegion[{x, y}, {{x, -1, 1}, {y, 1-x, 4 - x^2}}]; Region[R, Axes -> True, AxesLabel -> {x, y}, AxesOrigin -> {0, 0}] - Shade the region in the $xy$-plane that satisfies the inequalities $-3\leq y\leq 0$ and $0\leq x\leq \sqrt{9-y^2}$.

- Shade the region in the $xy$-plane that satisfies the polar coordinate inequalities $0\leq \theta\leq \pi$ and $1\leq r\leq 3$.

(*Remember that x = r Cos[theta] and y = r Sin[theta] for polar coordinates*) ParametricPlot[{r Cos[\[Theta]], r Sin[\[Theta]]}, {\[Theta], 0, \[Pi]}, {r, 1, 3}] R = ParametricRegion[{r Cos[\[Theta]], r Sin[\[Theta]]}, {{\[Theta], 0, \[Pi]}, {r, 1, 3}}]; Region[R, Axes -> True, AxesLabel -> {x, y}, AxesOrigin -> {0, 0}] - Shade the region in the $xy$-plane that satisfies the polar coordinate inequalities $-\frac{\pi}{6}\leq \theta \leq \frac{\pi}{6}$ and $0\leq r\leq 4\cos 3\theta$.

- Shade the region in the $xy$-plane that satisfies the polar coordinate inequalities $0\leq \theta\leq \frac{3\pi}{2}$ and $1\leq r\leq 3+2\cos\theta$.

We can also describe solid regions in space, using 3 sets of inequalities.

- Draw the region in space that satisfies the inequalities $0\leq x\leq 3$, $-1\leq y\leq 1$, and $0\leq z\leq 1-y^2$.

(*This code may take a while to generate an image, depending on your machine specs.*) R = ParametricRegion[{x, y, z}, {{x, 0, 3}, {y, -1, 1}, {z, 0, 1 - y^2}}]; Region[R, Axes -> True, AxesLabel -> {x, y, z}, AxesOrigin -> {0, 0, 0}] - Draw the region in space that satisfies the inequalities $-1\leq x\leq 1$, $0\leq y\leq 1-x^2$, and $0\leq z\leq 1-y$.

We will soon see that the area of the first region is given by the iterated double integral $\ds\int_{x=-1}^{x=1}\left(\int_{y=1-x}^{y=4-x^2}dy\right) dx$, written more compactly as $\ds\int_{-1}^{1}\int_{1-x}^{4-x^2}dy dx.$ The area of the second region is given by $\ds\int_{-3}^{0}\int_{0}^{\sqrt{9-y^2}}dx dy.$

The polar regions have areas given by the iterated double integrals $\ds\int_{0}^{\pi}\int_{1}^{3}rdr d\theta$, $\ds\int_{-\frac{\pi}{6}}^{\frac{\pi}{6}}\int_{0}^{4\cos 3\theta}rdr d\theta$, and $\ds\int_{0}^{\frac{3\pi}{2}}\int_{1}^{3+2\cos\theta}rdr d\theta$, where the $r$ that appears inside the integral is a stretch factor (called a Jacobian) that we'll learn how to obtain.

The regions in space have a volume given by the iterated triple integrals $\ds\int_{0}^{3}\int_{-1}^{1}\int_{0}^{1-y^2}dz dy dx$ and $\ds\int_{-1}^{1}\int_{0}^{1-x^2}\int_{0}^{1-y}dz dy dx$.

Task 2

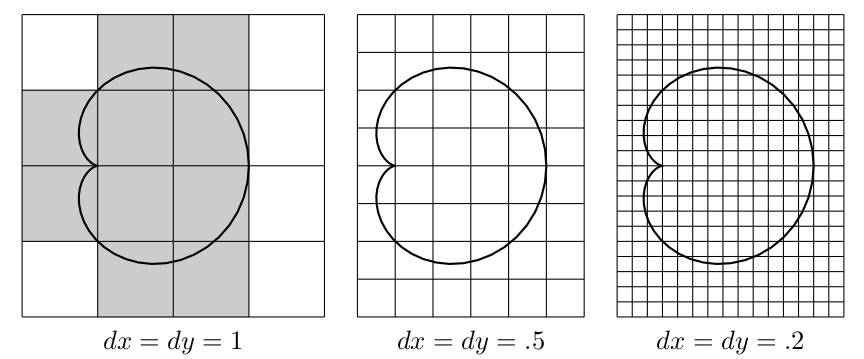

One way to compute the area of a region $R$ is overlay the region with a rectangular grid, where $dx$ and $dy$ are the distances between the vertical and horizontal lines of the grid. To find the area of the region, we first determine which of the rectangles contains a portion of the region $R$, and then add up the areas of of all such rectangles. This will overestimate the area, but we can then use limits to shrink both $dx$ and $dy$ to zero to obtain the area.

Consider the polar curve $r=1+\cos\theta$. We will use the approach described above to estimate the area of region $R$ that is inside this polar curve. We'll assume that all distances are given in meters. The bounds for each graph below are $-1\leq x\leq 2$ and $-2\leq y\leq 2$.

- For the first picture above, there are 10 rectangles (shaded) that contain a portion of the region $R$. Each of these rectangles has area $dA=dxdy=(1)(1) = 1 $, which means an overestimate for the area of $R$ is $A\approx 10 \, dA = 10(1)=10$. Describe a way to use these same rectangles to get an underestimate for the area of $R$.

- Now use the middle picture above (where $dx=dy=.5$) to shade and then count the number of rectangles that contain a portion of $R$. What is the area $dA$ of each little rectangle. Finish by giving an estimate for $A$.

- Now use the last picture with $dx=dy=.2$ to estimate the area of $R$.

- How can we obtain the exact value for the area of $R$?

- The questions above help focus on finding area, because each rectangle was given the same importance in the overall sum. Suppose instead that an object is made in the shape of the cardioid, but the portion that lies above the $x$-axis has a density of 2 kg/m^2, while the portion below has a density of 3 kg/m^2. How would you modify your work above to give an estimate for the mass (in kg)?

Task 3

In this task, we'll focus on the integrals $\int_C dx$ and $\int_C dy$, and from them develop a way to compute area using iterated (repeated) integrals.

- Consider the portion of the ellipse parametrized by $\vec r(t) = (3\cos t, 4\sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq \pi/2$. Notice that parametrization starts at $(3,0)$ and ends at $(0,4)$. The integral $\int_C dx$ literally says ``Sum up little changes in $x$.'' Adding up little changes in $x$ gives the total change in $x$.

- Differentials gives us $dx = -3\sin t dt$. Compute $\ds\int_C dx=\int_{t=0}^{t=\pi/2}dx = \ds\int_{t=0}^{t=\pi/2}-3\sin t dt$ and verify that it gives the total change in $x$ from $t=0$ to $t=\pi/2$.

- Guess the value of $\ds\int_{t=0}^{t=\pi/2}dy$ (the integral adds up what?), and then check your solution.

- Consider the region $R$ between the functions $y=x^2$ and $y=-x$ for $0\leq x\leq 3$. Our goal is to explain why the iterated integral $\ds\int_{x=0}^{x=3}\left(\int_{y=-x}^{y=x^2} dy \right)dx$ gives the area of the region $R$.

- Draw both functions and shade the region $R$. (You can use the ParametricPlot[] command, see the first task, to check your work.)

- Compute the integral $\ds\int_{y=-x}^{y=x^2}dy$ for arbitrary $x$. This integral computes, for a given value of $x$, the total change in $y$ (so a height). You can check how you did with Mathematica

Integrate[1, {y, -x, x^2}] - Recall that $dx$ is a small width. When we multiply the previous integral by this width $dx$, we will obtain the area of a small rectangular region whose height is given by $\ds\int_{y=-x}^{y=x^2}dy$ and width is given by $dx$. Pick a value $x$ between 0 and 3, and then construct a picture that illustrates this rectangular region whose area is given by $dA=\ds\left(\int_{y=-x}^{y=x^2} dy \right)dx$.

- Explain why $\ds\int_{x=0}^{x=3}\left(\int_{y=-x}^{y=x^2} dy \right)dx$ gives the area of the region $R$.

- Compute the integral, and then run the Mathematica code below to check your work above and learn how to code iterated integrals.

(*One of the options below is incorrect.*) Integrate[Integrate[1, {y, -x, x^2}], {x, 0, 3}] Integrate[1, {x, 0, 3}, {y, -x, x^2}] Integrate[1, {y, -x, x^2}, {x, 0, 3}]

- Consider the double integral $$\int_{y=-1}^{y=2}\left(\int_{x=y^2}^{x=y+2}dx\right)dy.$$

- The bounds in the integral above describe a region in $xy$-plane where $-1\leq y\leq 2$ and $y^2\leq x\leq y+2$. Sketch this region.

- Consider the inner integral $\int_{x=y^2}^{x=y+2}dx$. This integral adds up changes in $x$, so gives a total change in $x$ (hence a width). Add to your sketch several line segments whose widths are given by this integral.

- When we multiply a width $\int_{x=y^2}^{x=y+2}dx$ by a small height $dy$, we get a little bit of area $dA$. Pick a value $y$ between $-1$ and $2$, and then at that height draw a small rectangle whose area is given by $dA = \left(\int_{x=y^2}^{x=y+2}dx\right) dy$.

- Adding up little bits of area gives total area, so the double integral $$\int_{y=-1}^{y=2}\left(\int_{x=y^2}^{x=y+2}dx\right)dy$$ gives an area. Compute the integral.

- Check with Mathematica, using the Integrate[] command.

Self Check

I'll occasionally add relevant problems from OpenStax. As needed, spend a few minutes working on some exercises below. If you get stuck on a prep task, feel free to bring a solution to one of the textbook exercises to share.

- Pick some problems related to the topics we are discussing from the Text Book Practice page.

Task 4

In this task we'll be focusing on locating the average, mean, center, etc., of something.

- Suppose a class takes a test and there are three scores of 70, five scores of 85, one score of 90, and two scores of 95. We will calculate the average class score, $\bar s$, four different ways to emphasize four ways of thinking about the averages. We are emphasizing the pattern of the calculations in this problem, rather than the final answer, so it is important to write out each calculation completely, without doing any simplifying, before calculating the number $\bar s$.

- Compute the average by adding 11 numbers together and dividing by the number of scores ($\bar s=\frac{\sum \text{values}}{\text{number of values}}$). Write down the whole computation before doing any arithmetic.

- Compute the numerator of the fraction in the previous part by multiplying each score by how many times it occurs, rather than adding it in the sum that many times ($\bar s=\frac{\sum (\text{value}\cdot\text{weight})}{\sum \text{weight}}$). Again, write down the calculation for $\bar s$ before doing any arithmetic.

- Compute $\bar s$ by splitting up the fraction in the previous part into the sum of four numbers ($\bar s=\sum (\text{value}\cdot\text{(\% of stuff)})$). This is called a weighted average because we are multiplying each score value by a weight.

- Another way of thinking about the average $\bar s$ is that $\bar s$ is the number so that if all 11 scores were the same value $\bar s$, you'd have the same sum of scores ($\text{ (number of values) }\bar s = \sum \text{values}$ or $(\sum \text{weight})\bar s = \sum (\text{value}\cdot\text{weight})$). Write this way of thinking about these computations by taking the formulas for $\bar s$ in the first two parts and multiplying both sides by the denominator.

We now generalize the above ways of thinking about averages from a discrete situation to a continuous situation. We did this in first-semester calculus when we computed the average value of $f$ using integrals.

- Suppose the price of a stock is \$10 for two days. Then the price of the stock jumps to \$20 for three days. Our goal is to determine the average price of the stock over the total 5 day period.

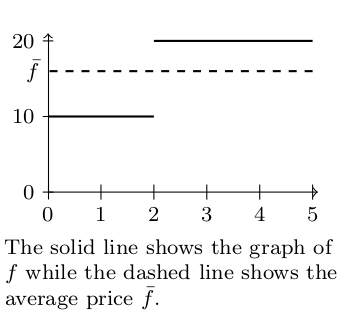

- Why is the average stock price not \$15? Use any of the methods from the previous problem to show that the average price is $\bar f=\$16$.

- The function $f(t) = \begin{cases}10 &0\leq t<2\\20&2\leq t\leq 5\end{cases}$ models the price of the stock for the 5-day period. The graph below shows both the function $f$ and the average stock price $\bar f$. Show that the area under $f$ for $0\leq t\leq 5$ is 80. Then show that the area under $\bar f$ for $0\leq t\leq 5$ is also 80.

- The average value of a function over an interval $ [a,b] $ is a constant value $\bar f$ so that the areas under both $f$ and $\bar f$ are equal, which means $\ds\int_a^b \bar f dx = \int_a^b f dx.$ Solve for $\bar f$ to show that $$\bar f = \dfrac{\ds\int_a^b f dx}{\ds\int_a^b dx}.$$

Let's examine one last averaging question, this time as it relates to a rover. If we know the mass and center-of-mass of each part of the rover, we can use weighted averages to combine these values and obtain the center-of-mass of the the entire rover.

- Consider a simplified rover with a bottom and a top.

- The bottom part of the rover has a volume of $V_1$ m$^3$, a constant density (mass per volume) of $\delta_1$ g/m$^3$, and a center-of-mass located at $(\bar x_1,\bar y_1,\bar z_1)$.

- The top part of the rover has a volume of $V_2$ m$^3$, a constant density (mass per volume) of $\delta_2$ g/m$^3$, and a center-of-mass located at $(\bar x_2,\bar y_2,\bar z_2)$.

- Give the masses $m_1$ and $m_2$ of the bottom and top of the rover. Explain.

- What proportion of the total mass comes from the bottom of the rover?

- Explain why the center-of-mass of the entire rover is $$\left(\frac{\bar x_1(m_1)+\bar x_2(m_2)}{m_1+m_2},\frac{\bar y_1(m_1)+\bar y_2(m_2)}{m_1+m_2}, \frac{\bar z_1(m_1)+\bar z_2(m_2)}{m_1+m_2}\right) .$$

- The rover picks up an additional object. The object's mass is $m_3$ with center-of-mass $(\bar x_3, \bar y_3, \bar z_3)$. Modify the formula above to give the center-of-mass of the rover, together with the new object. Try writing the formula using summation notation.

Task 5

To find the mass of a thin metal plate occupying a region $R$ in the $xy$-plane, we add up the little masses (differentials) $dm = \delta(x,y)dA$, where $\delta$ is the density (mass per area), to obtain the mass as $$m=\iint_R\delta(x,y)dA = \iint_R\delta(x,y) dxdy= \iint_R\delta(x,y) dydx. $$ Note that if $\delta(x,y)=1$, then this reduces to the formula for the area of $R$. This task has you practice setting up area and mass integrals.

For each region $R$ below, draw the region. Then set up an iterated double integral which would give the area of the region. Then use the density provided to set up an iterated double integral that would give the mass of a metal plate occupying this region with the given density. You do not need to compute each integral, rather just set it up.

- The region $R$ is above the line $x+y=1$ and inside the circle $x^2+y^2=1$. The density is $\delta(x,y)=x$.

- The region $R$ is below the line $y=8$, above the curve $y=x^2$, and to the right of the $y$-axis. The density is $\delta(x,y)=xy^2$.

- The region $R$ is bounded by $2x+y=3$, $y=x$, and $x=0$. The density is $\delta(x,y)=7$.

Once we have an iterated double integral whose bounds appropriately describe a region, we can use Mathematica to quickly draw the region (verifying our bounds are correct) and then compute the integral. For example, given the integral $\ds\int_{-1}^{1}\int_{-x}^{4-x^2}y^2dydx$, the following code draws the region and computes the integral.

outerB = {x, -1, 1}

innerB = {y, -x, 4 - x^2}

ParametricPlot[{x, y}, outerB, innerB, Mesh -> {10, 0}]

Integrate[y^2, outerB, innerB]

% // N

- For each of the 3 regions above, adapt the Mathematica code to draw the region and compute its mass.

Task 6

Polar coordinates is a type of new coordinate system. Polar coordinates helps describe planar regions that have some kind of rotational symmetry. We've actually been using change-of-coordinates since first semester calculus, every time we perform a substitution to complete an integral. What we'll do in this task is look at two changes-of-coordinates, one which stretches lengths, and the other which stretches areas.

- Consider the integral $\ds\int_{-1}^{2} e^{-3x}\, dx$.

- To complete this integral we use the substitution $u=-3x$. Solve for $x$ and compute the differential $dx$.

- Perform the substitution, filling in the missing parts of $$\int_{x=-1}^{x=2} e^{-3x}\, dx = \int_{u=?}^{u=?} e^{u}? du.$$ Note that when a definite integral ends with $du$, the bounds should be in terms of $u$. To find the $u$ bounds, just ask, "If $x=-1$, then $u=?$" Don't spend any time completing the integral, rather just focus on completing the substitution above.

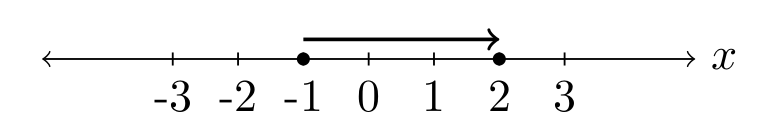

- The $x$ values range from $-1$ to $2$. This is a directed interval whose width is 3 units, pointing from left to right along the $x$-axis (shown below). Our substitution $u=-3x$ transforms this directed interval into a different directed interval along the $u$-axis. Draw the transformed directed interval (include the direction) on the $u$-axis below.

- How long is the new interval along the $u$-axis? What does your differential equation $dx=-\frac{1}{3}du$ have to do with this problem? What does the negative sign do?

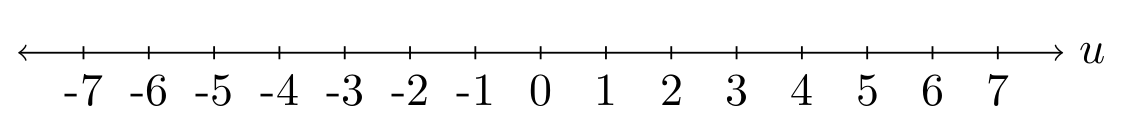

Above we showed that the differential equation $dx = \frac{dx}{du}du$ tells us how to relate lengths along the $u$-axis to lengths along the $x$-axis. We could think of the number $\frac{dx}{du}$ as a length stretch factor. Let's now examine a two dimensional change-of-coordinates, and connect areas in the $uv$-plane to areas in the $xy$-plane.

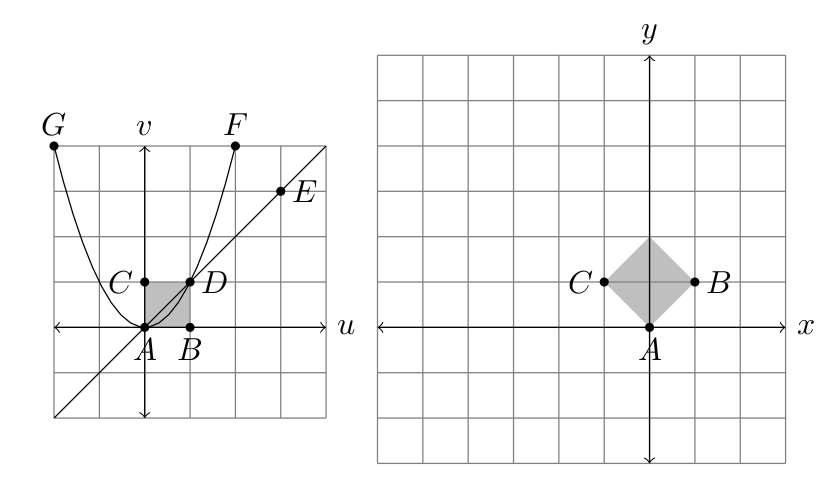

- Consider the change-of-coordinates $x=u-v$ and $y=u+v$, which we could also write as the coordinate transformation $\vec T(u,v) = (u-v,u+v)$.

- In the table below, you're given several $(u,v)$ points. Find the corresponding $(x,y)$ pair. $$ \begin{array}{|c|c|c|} \text{Name}&(u,v)&(x,y)\\\hline A&(0,0)&(0,0)\\ B&(1,0)&(1-0,1+0) = (1,1)\\ C&(0,1)&(0-1,0+1) = (-1,1)\\ D&(1,1)&\\ E&(3,3)&\\ F&(2,4)&\\ G&(-2,4)&\\ \end{array}$$

- There are two graphs below. One is a plot in the $uv$-plane of the points from the table, along with the parabola $v=u^2$, the line $v=u$, and the shaded box whose corners are the first four points. Complete a similar plot in the $xy$-plane by adding the remaining points, and then connect the points in your $xy$ plot to show how the parabola, line, and shaded box (done for you) transform because of this change-of-coordinates.

- The following Mathematica code allows you to draw any region from the $uv$-plane in the $xy$ plane. You can use it to check your work (as well as adapt the code to work with ANY new coordinate system).

R1 = ParametricRegion[{{u - v, u + v}, 0 <= u <= 1 && 0 <= v <= 1}, {u, v}]; Region[R1, Axes -> True, AxesLabel -> {x, y}] R2 = ParametricRegion[{{u - v, u + v}, v == u^2}, {{u, -2, 2}, v}]; Region[R2, Axes -> True, AxesLabel -> {x, y}]

- How would you describe what this change-of-coordinates is doing?

- The differential of $x$ is $dx = du-dv$. Obtain a similar formula for the differential $dy$. Then write your answer as the vector equation (linear combination) $$\begin{pmatrix}dx\\dy\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 1\\ ?\end{pmatrix}du+\begin{pmatrix}-1\\?\end{pmatrix}dv.$$

- The area of the shaded 1 by 1 box in the $uv$-plane is 1. What is the area of the corresponding shaded region in the $xy$-plane?

- If we knew an object in the $uv$ plane had area 6, make a guess for what the area of the region would be in the $xy$-plane? Explain why you made that guess.

We'll develop a tool that helps us understand how areas are stretched by a transformation. This area stretch factor we call a "Jacobian". We'll soon have a way to compute a Jacobian, which will result from finding the area of a parallelogram (the next task).

Task 7

We need a quick way to compute the area of a parallelogram. In this task, we'll prove the following theorem and then use it in a few specific examples.

The area $A$ of a parallelogram whose edges are the two vectors $\vec u= (a,b)$ and $\vec v = (c,d)$ is given by $A=|ad-bc|$.

- Suppose a parallelogram has edges that are parallel to the vectors $\vec u=(a,b)$ and $\vec v=(c,d)$. Prove that the area of this parallelogram is given by $|ad-bc|$. If you want some help, here are some steps you can follow:

- Draw a generic parallelogram. Label one corner the origin, and then the two connecting edges are the vectors $\vec u = (a,b)$ and $\vec v=(c,d)$.

- Add to your picture (1) the projection of $\vec u$ onto $\vec v$ (so $\vec u_{\parallel \vec v}$) and (2) the component of $\vec u$ that is orthogonal to $\vec v$ (so $\vec u_{\perp \vec v}$).

- Explain why the area is $A = |\vec v||\vec u_{\perp \vec v}|$.

- Use the Mathematica code below to quickly compute and simplify $|\vec v||\vec u_{\perp \vec v}|$. Then explain why the result is equal to $|ad-bc|$.

u = {a, b}; v = {c, d}; uPerpv = u - Projection[u, v]; Norm[uPerpv]*Norm[v] // FullSimplify

- Whether you are able to complete the proof above or not, let's practice using the result to compute areas of parallelogram (and triangles). Use the area formula $|ad-bc|$ to compute the requested areas below.

- A parallelogram has vertices $(0,0)$, $(-2,5)$, $(3,4)$, and $(1,9)$. Find its area.

- Find the area of the triangle with vertices $(0,0)$, $(-2,5)$, and $(3,4)$.

- Find the area of the triangle with vertices $(-3,1)$, $(-2,5)$, and $(3,4)$. [You'll need to give vectors $\vec u$ and $\vec v$ that form the edges of a parallelogram.]

Self Check

I'll occasionally add relevant problems from OpenStax. As needed, spend a few minutes working on some exercises below. If you get stuck on a prep task, feel free to bring a solution to one of the textbook exercises to share.

- Pick some problems related to the topics we are discussing from the Text Book Practice page.

Task 8

We can think of any object (such as a rover) as consisting of many little parts. Each little part contributes a little mass $dm$ and a center-of-mass. We can predict these quantities prior to building the rover, before we can weigh anything. We just need the length $ds$, area $dA$, or volume $dV$ of a small part, together with the material's density $\delta$ (mass per length, area, or volume, as appropriate).

- For thin wires, we get little masses $dm$ by multiplying little lengths $ds$ by a density $\delta$ with units of mass per length.

- For thin plates, we get little masses $dm$ by multiplying little areas $dA$ by a density $\delta$ with units of mass per area.

- For solid objects, we get little masses $dm$ by multiplying little volumes $dV$ by a density $\delta$ with units of mass per volume.

In all three cases, we can obtain the total mass $m$ by adding up the little masses with an integral. The difference between the three cases will be whether we use a single, double, or triple integral. Often the density $\delta$ will be constant throughout an entire object. However, composite materials exist where density $\delta (x,y,z)$ can vary throughout an object. We can then compute the center-of-mass using the average value formula.

Consider a thin rod (like a drive shaft or thinner) that lies along the $z$-axis for $a\leq z\leq b$.

- Suppose first that the rod is made out of a single material whose density is given by the constant $\delta$ g/m (mass per length).

- A small part of the rod has length $dz$. Compute $\int_a^b dz$, and explain what physical quantity this integral computes.

- A small bit of the rod has mass $dm = \delta dz$. Compute the total mass by computing $\int_a^b \delta dz$. Remember that $\delta$ is a constant.

- Guess the location of the average $z$-value of the rod (the center-of-mass).

- To validate your guess, compute and simplify the average value integral formula $$\bar z = \frac{\ds\int_a^b z dm}{\ds\int_a^b dm} = \frac{\ds\int_a^b z \delta dz}{\ds\int_a^b \delta dz}.$$

- Now suppose the rod is more like an antenna and the rod gets thinner as we move up the rod. This means the density $\delta(z)$ is now a function of $z$. Let's use, for simplicity, the linear density function $\delta(z)=b-z$.

- What is the density of the rod at $a$? What is the density of the rod at $b$? Construct a rough sketch of a rod that could have this type of density function.

- A small bit of the rod has mass $dm = \delta(z) dz$. Compute the total mass by computing $\int_a^b \delta(z) dz = \int_a^b (b-z)dz$.

- Is the location of $\bar z$ closer to $z=a$ or $z=b$? Explain.

- Find the $z$-coordinate of the center-of-mass by computing $$\bar z = \frac{\ds\int_a^b z dm}{\ds\int_a^b dm} = \frac{\ds\int_a^b z \delta dz}{\ds\int_a^b \delta dz}.$$ Please use software (so something along the lines Integrate[]/Integrate[]). Verify that $\bar z = \frac{2a+b}{3}$.

Above we performed computations for a rod that lies on an axis. This works great for a drive shaft, or antenna, or any part of the rover that consists of a straight thin rod. But we can repeate these computations for a portion of the rover that is a thin flat plate, such as a solar panel, an armored plate, or any object which is best described by thinking of the area.

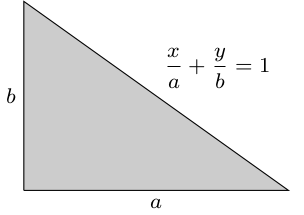

- Consider the triangular region $R$ in the first quadrant that lies under the line $\ds\frac{x}{a}+\frac{y}{b}=1$. If you would rather work with numbers instead of variables, feel free to let $a=5$ and $b=7$ in this problem.

- Compute the double integral $\ds\int_0^a\int_0^{b(1-\frac{x}{a})} dy dx$. What physical quantity of the region $R$ does this integral give?

- The density of the metal plate is $\delta$ g/m$^2$. Set up a double integral formula to compute the mass of the region using this density.

- The center-of-mass in the $x$-direction is given by the formula $$\bar x = \frac{\ds\iint_R xdm}{\ds\iint_R dm}= \frac{\ds\int_0^a\int_0^{b(1-\frac{x}{a})} x \delta dy dx}{\ds\int_0^a\int_0^{b(1-\frac{x}{a})} \delta dy dx}.$$ Assuming $\delta$ is constant, compute this integral and show that $\bar x = \frac{a}{3}$. Feel free to use Mathematica or do the integral by hand.

- Set up an integral formula, like the one above, to compute $\bar y$. Show the integral formula you used, and use Mathematica to compute $\bar y$.

Task 9

- Consider the region $R$ in the $xy$-plane that is below the line $y=x+2$, above the line $y=2$, and left of the line $x=5$. We can describe this region by saying for each $x$ with $0\leq x\leq 5$, we want $y$ to satisfy $2\leq y\leq x+2$. In set builder notation, we write $$R=\{(x,y)\in \mathbb{R}^2\mid 0\leq x\leq 5, 2\leq y\leq x+2\}.$$ We use the symbols $\{$ and $\}$ to enclose sets and the symbol $\mid$ for "such that". We read the above line as "$R$ equals the set of $(x,y)$ in the plane such that zero is less than $x$ which is less than 5, and 2 is less than $y$ which is less than $x+2$." The iterated double integral $\int_0^5\int_2^{x+2} dy dx$ gives the area of this region.

- Draw this region. Check with Mathematica.

outerB = {x, 0, 5} innerB = {y, 2, x + 2} ParametricPlot[{x, y}, outerB, innerB, Mesh -> {10, 0}] - Describe the region $R$ by saying for each $y$ with $c\leq y\leq d$, we want $x$ to satisfy $a(y)\leq x\leq b(y)$. In other words, find constants $c$ and $d$, and functions $a(y)$ and $b(y)$, so that for each $y$ between $c$ and $d$, the $x$ values must be between the functions $a(y)$ and $b(y)$. Write your answer using the set builder notation $$R=\{(x,y)\ | \ c\leq y\leq d, a(y)\leq x\leq b(y)\}.$$ Then use the bounds to set up the iterated double integral $\int_?^?\int_?^? dx dy$ whose value will give the same area.

- Enter your new bounds into the Mathematica code below to verify that you have the correct bounds (the graph will be the same, but the mesh lines will now run left-to-right instead of bottom-to-top).

outerB = {y, , } innerB = {x, , } ParametricPlot[{x, y}, outerB, innerB, Mesh -> {10, 0}] - Compute both $\int_0^5\int_2^{x+2} dy dx$ and $\int_?^?\int_?^? dx dy$ (the integral you just set up) to verify that they both give the same value.

- Draw this region. Check with Mathematica.

- Consider the iterated integral $\ds \int_0^3\int_x^3 e^{y^2}dydx$. We could think of the function $e^{y^2}$ as a density, but notice that this function is independent of the region described by the bounds of the integral.

- Write the bounds as two inequalities ($0\leq x\leq 3$ and $?\leq y\leq ?$). Then draw and shade the region $R$ described by these two inequalities. (Check with Mathematica.)

- Swap the order of integration from $dydx$ to $dxdy$. This forces you to describe the region using two inequalities of the form $c\leq y\leq d$ and $a(y)\leq x\leq b(y)$, obtaining the iterated double integral $\ds \int_?^?\int_?^? e^{y^2}dxdy$. (You can check that you have the correct solution using Mathematica.)

- Use your new bounds to compute the integral by hand.

- Try computing the inner integral $\int_x^3 e^{y^2}dy$ by hand (but don't spend too long). What does Mathematica give as a value?

- Check that your work is correct, by updating the bounds in the second half of the code below. Note that you should obtain the same picture with both sets of bounds, the only difference being the mesh lines will be horizontal instead of vertical.

outerB = {x, 0, 3} innerB = {y, x, 3} ParametricPlot[{x, y}, outerB, innerB, Mesh -> {10, 0}] Integrate[Exp[y^2], outerB, innerB] outerB = {y, ,} innerB = {x, ,} ParametricPlot[{x, y}, outerB, innerB, Mesh -> {10, 0}] Integrate[Exp[y^2], outerB, innerB]

Task 10

It's time to focus on how area is changed when we perform a change-of-coordinates. We'll see that finding the area of a transformed parallelogram is the key.

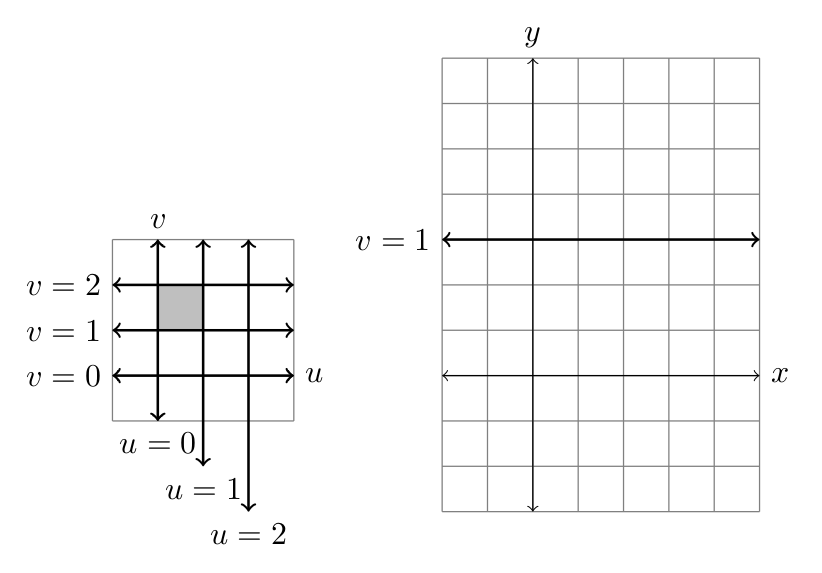

- Consider the change-of-coordinates $x=2u$, $y=3v$.

- The lines $u=0,u=1,u=2$ and $v=0,v=1,v=2$ correspond to lines in the $xy$-plane. Draw these lines in the $xy$-plane (the line $v=1$ is done for you).

- The box in the $uv$-plane with $0\leq u\leq 1$ and $1\leq v\leq 2$ corresponds to a box in the $xy$-plane. Shade this box in the $xy$-plane and find its area.

- Compute the differentials $dx$ and $dy$. State them using the vector form (linear combination) $$\begin{pmatrix}dx\\dy\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} ?\\ ?\end{pmatrix}du+\begin{pmatrix}?\\?\end{pmatrix}dv$$ What do the two vectors $(a,0)$ and $(0,b)$ have to do with your picture?

- Draw the box given by $-1\leq u\leq 1$ and $-1\leq v\leq 1$ in both the $uv$-plane and $xy$-plane. Then state the area $A_{uv}$ of this box in the $uv$-plane, and state the area $A_{xy}$ of the corresponding rectangle in the $xy$-plane.

- Consider the circle $u^2+v^2=1$, whose area inside is $A_{uv}=\pi$. Guess the area $A_{xy}$ inside the corresponding ellipse in the $xy$-plane. Explain.

- The lines $u=0,u=1,u=2$ and $v=0,v=1,v=2$ correspond to lines in the $xy$-plane. Draw these lines in the $xy$-plane (the line $v=1$ is done for you).

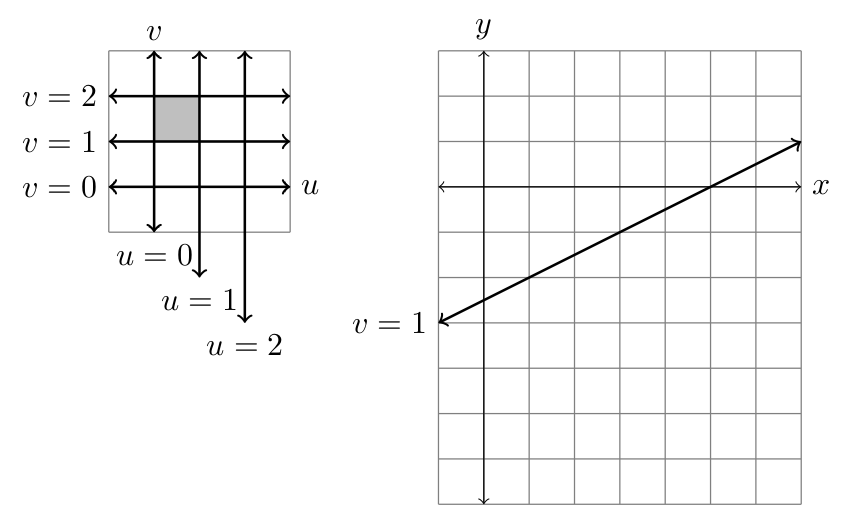

- Consider now the change-of-coordinates $x=2u+v$, $y=u-2v$.

- The lines $u=0,u=1,u=2$ and $v=0,v=1,v=2$ correspond to lines in the $xy$ plane. Draw these lines in the $xy$-plane (the line $v=1$ is drawn for you). One option is to find the $xy$ coordinates of the $(u,v)$ points $(0,0)$, $(0,1)$, $(0,2)$, $(1,0)$, $(1,1)$, etc., and then just connect the dots to make a rotated grid.

- The box in the $uv$-plane with $0\leq u\leq 1$ and $1\leq v\leq 2$ should correspond to a parallelogram in the $xy$ plane. Shade this parallelogram in your picture above.

- Compute the differentials $dx$ and $dy$. State them using the vector form (linear combination) $$\begin{pmatrix}dx\\dy\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} ?\\ ?\end{pmatrix}du+\begin{pmatrix}?\\?\end{pmatrix}dv.$$ What do the two vectors above have to do with your picture?

- Show that the area of the parallelogram formed using these two vectors is 5. How would you describe the change in area between the graph in the $uv$-plane, and the graph in the $xy$-plane?

- The lines $u=0,u=1,u=2$ and $v=0,v=1,v=2$ correspond to lines in the $xy$ plane. Draw these lines in the $xy$-plane (the line $v=1$ is drawn for you). One option is to find the $xy$ coordinates of the $(u,v)$ points $(0,0)$, $(0,1)$, $(0,2)$, $(1,0)$, $(1,1)$, etc., and then just connect the dots to make a rotated grid.

The following code will help you check that your work on the second part is correct.

coordinates = {2 u + v, u - 2 v}

R = ParametricRegion[{coordinates, 0 <= u <= 1 && 1 <= v <= 2}, {u, v}];

Region[R, Axes -> True, AxesLabel -> {x, y}, AxesOrigin -> {0, 0}]

R = ParametricRegion[{coordinates, u == 0 || u == 1 || u == 2 || v == 0 || v == 1 || v == 2}, {{u, -1, 3}, {v, -1, 3}}];

Region[R, Axes -> True, AxesLabel -> {x, y}, AxesOrigin -> {0, 0}]

Task 11

Consider the change-of-coordinates $x=r\cos \theta$ and $y=r\sin\theta$.

- The lines $r=1,r=2,r=3$ and $\theta=0,\theta=\frac{\pi}{6},\theta=\frac{\pi}{3}$ correspond to circles and lines in the $xy$ plane. Draw these circles and lines in the $xy$-plane.

- The box in the $r\theta$ plane with $2\leq r\leq 3$ and $\frac{\pi}{6}\leq \theta\leq \frac{\pi}{3}$ corresponds to a region in the $xy$ plane. Shade this region in the $xy$ plane.

- Let $(r,\theta)$ be an arbitrary point. Our goal is to develop a formula for the area of the region $R$ in the $xy$ plane where the radius ranges from $r$ to $r+dr$ and the angle ranges from $\theta$ to $\theta +d\theta$, shown in the diagram below.

- Add the labels $r$, $\theta$, $dr$, $d\theta$, $r+dr$, and $\theta +d\theta$ to appropriate places in your diagram.

- The shaded region is approximately a rectangle. Letting the width of the rectangle be $dr$, explain why the height of the rectangle can be approximated by $rd\theta$. This means that a little area is given by $dA=rdrd\theta$.

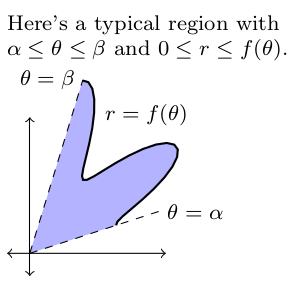

- Consider the region $R$ in the $xy$ plane bounded by $\alpha\leq \theta\leq \beta$ and $0\leq r\leq f(\theta)$ (shown below). The area of such a region $R$ in the $xy$ plane is the double integral $A=\int\int_R dA$. Explain why the area of the region in the $xy$ plane, when using polar coordinates, is $$A=\int_\alpha^\beta\int_0^{f(\theta)} rdrd\theta.$$

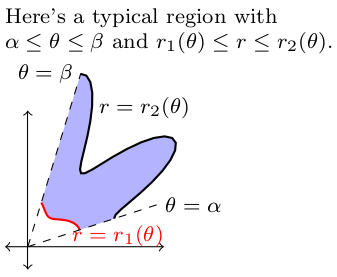

- Now consider the region $R$ bounded by $\alpha\leq \theta\leq \beta$ and $r_1(\theta)\leq r\leq r_2(\theta)$. Set up a double integral that would give the area of this region $R$.

Task 12

Given a change-of-coordinates $x = x(u,v)$ and $y=y(u,v)$, the differential is $$\begin{pmatrix}dx\\dy\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \frac{\partial x}{\partial u}\\ \frac{\partial y}{\partial u}\end{pmatrix}du+\begin{pmatrix}\frac{\partial x}{\partial v}\\\frac{\partial y}{\partial v}\end{pmatrix}dv = \begin{bmatrix}\frac{\partial x}{\partial u}&\frac{\partial x}{\partial v}\\\frac{\partial y}{\partial u}&\frac{\partial y}{\partial v}\end{bmatrix}\begin{pmatrix}du\\dv\end{pmatrix}.$$ The Jacobian of the change-of-coordinates, written $\dfrac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)}$, is the area of the parallelogram formed by the partial derivatives $\dfrac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial u}=\begin{pmatrix} \frac{\partial x}{\partial u}\\ \frac{\partial y}{\partial u}\end{pmatrix}$ and $\dfrac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial v}=\begin{pmatrix} \frac{\partial x}{\partial v}\\ \frac{\partial y}{\partial v}\end{pmatrix}$. The Jacobian, in 2D, is an area stretch factor that relates the area $A_{uv}$ of a small region in the $uv$-plane to the transformed region of area $A_{xy}$ in the $xy$-plane, which we often summarize with the notation $dA = \frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)}dudv.$ In terms of integrals, this gives $$\iint_R f dxdy =\iint_R f dA = \iint_R f \frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)}dudv.$$ The Jacobian can be computed in 3D similarly, and is defined as the volume of the parallelepiped (see below) formed by the three partial derivatives of a three dimensional change-of-coordinates. Similar definitions hold in all dimensions, with the same application.

- Use the area of a parallelogram formula we developed to explain why the Jacobian can be computed using the formula $$\frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)} = \left|\frac{\partial x}{\partial u}\frac{\partial y}{\partial v}-\frac{\partial x}{\partial v}\frac{\partial y}{\partial u}\right|.$$

- For the polar coordinate transformation given by the change-of-coordinates $x=r\cos\theta$ and $y=r\sin\theta$, compute the differential $(dx,dy)$, and then show that the Jacobian is $\ds\frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (r,\theta)} = |r|$. This provides another verification that $dA = |r| drd\theta$ when setting up double integrals using polar coordinates, where we can drop the absolute values provided we require $r\geq 0$. The Mathematica notebook JacobianIllustration.nb provides a visual representation of the Jacobian (as well as computes it). You can check your work on all parts of this task by using this notebook.

- For the change-of-coordinates $x=2u-v$ and $y=u+2v$, compute the differential $(dx,dy)$, and then obtain the Jacobian $\ds \frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)}$.

- For the change-of-coordinates $x=au$ and $y=bv$, show that the Jacobian is $\ds \frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)}=|ab|$.

- For the change-of-coordinates $u=x+y$ and $v=x-y$, show that $\ds \frac{\partial (u,v)}{\partial (x,y)} = 2$.

- For the change-of-coordinates $u=x+y$ and $v=x-y$, first solve for $x$ and $y$ in terms of $u$ and $v$ (so obtain $x = ....$ and $y= ...$). Then show that $\ds \frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)} = \frac{1}{2}$.

Did you notice that $\ds \frac{\partial (u,v)}{\partial (x,y)} = \left(\ds \frac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)}\right)^{-1}$?

Task 13

For each region $R$ below, draw the region in the $xy$-plane. Set up an iterated integral in polar coordinates ($x=r\cos\theta$, $y=r\sin\theta$) that gives the area of the region and then use the given density to set up an iterated double integral that gives the mass of a metal plate that occupies the region and has the given variable density. Use software to compute each integral.

For example, consider the region that is inside the circle $x^2+y^2=9$, along with the density $\delta(x,y)=y^2$. We can describe the region using the polar inequalities $0\leq \theta \leq 2\pi$ and $0\leq r\leq 3$, which gives us the bounds needed for our integral.

- The area is $\ds A=\iint_R \delta dA = \int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^3\underbrace{rdrd\theta}_{dA} = 9\pi.$

- The mass is $\ds m=\iint_R \delta dA = \int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^3\underbrace{(r\sin\theta)^2}_{\delta=y^2}\underbrace{rdrd\theta}_{dA} = \frac{81\pi}{4}.$

The Mathematica code below was used to compute the integrals above (along with a graphical check that the region is the correct region).

ClearAll[r,theta]

outerB = {theta, 0, 2 Pi};

innerB = {r, 0, 3};

Integrate[r, outerB, innerB]

Integrate[(r Sin[theta])^2 r, outerB, innerB]

coordinates = {r Cos[theta], r Sin[theta]};

ParametricPlot[coordinates, outerB, innerB, Mesh -> {10, 0}]

- The region $R$ is the quarter disc in the first quadrant that lies inside the circle $x^2+y^2=25$. The density is $\delta(x,y)=x$.

- The region $R$ is bounded above by $y=\sqrt{9-x^2}$, bounded below by $y=x$, and bounded on the left by the $y$-axis. The density is $\delta(x,y)=xy^2$.

- The region $R$ is the inside of the cardioid $r=3+3\cos\theta$. The density is $\delta(x,y)=7$.

- The region $R$ is the triangular region below $y=\sqrt 3 x$, above the $x$-axis, and to the left of $x=1$. The density is $\delta(x,y)=7$.

Task 14

We have seen how to compute the center of mass of a rod (a 1 dimensional object) and triangle (a 2 dimensional object). This task will do so with a circular region (2 dimensional object) and 3D solid.

- Consider the semicircular disc $R$ that lies above the $x$-axis and below the circle of radius $a$. If you would rather work with numbers instead of variables, feel free to let $a=5$ for this problem.

- We know the area of $R$ is $\frac{1}{2}\pi a^2$. Set up a double integral using polar coordinates to compute this area. Then compute the integral by hand and simplify your work to obtain the correct area.

- Let's assume the density for this problem is $\delta = 1$, so that $dm=dA$. When the density is constant, we use the word "centroid" instead of "center-of-mass" to talk about the geometric center of an object. The centroid in the $x$-direction is given by the formula $$\bar x = \frac{\ds\iint_R xdA}{\ds\iint_R dA}= \frac{\ds\int_0^\pi\int_0^{a} \overbrace{(r\cos\theta)}^{x} \overbrace{r dr d\theta}^{dA}}{\ds\int_0^\pi\int_0^{a} \underbrace{r dr d\theta}_{dA}}.$$ Compute the integrals above, by hand, to show that $\bar x=0$. Use the Mathematica code below to check how you did. Note that to create the plot, we must replace $a$ with a variable (hence the code /. a -> 5).

ClearAll[r, theta, a] outerB = {theta, 0, Pi}; innerB = {r, 0, a}; numerator = Integrate[r Cos[theta] r, outerB, innerB] denominator = Integrate[r, outerB, innerB] centerOfMass = numerator/denominator ParametricPlot[{r Cos[theta], r Sin[theta]}, outerB, innerB /. a -> 5, Mesh -> {10, 0}] - Set up an integral formula, like the one above, to compute $\bar y$. Show the integral formula you used, and then compute it (adapt the Mathematica code above) to obtain $\bar y$. Check your answer is correct by referring to a list of centroid of regions (such as this Wikipedia list).

- The triple integral $\ds\int_{0}^{5}\int_0^7\int_{0}^{10-2x}dzdydx$ gives the volume of a solid domain $D$ in space.

- Draw the solid domain $D$ described by the bounds of the integral above. This is the solid satisfying the inequalities $0\leq x\leq 5$, $0\leq y\leq 7$, and $0\leq z\leq 10-2x$. Use the Mathematica code below to check that your plot is correct.

outerB = {x, 0, 5}; middleB = {y, 0, 7}; innerB = {z, 0, 10 - 2 x}; R = ParametricRegion[{x, y, z}, Evaluate[{outerB, middleB, innerB}]]; Region[R, Axes -> True, AxesLabel -> {x, y, z}, AxesOrigin -> {0, 0, 0}] - Let $\delta =1$ so that $dm=\delta dV = 1dV$. The centroid of $D$ has three coordinates $(\bar x, \bar y, \bar z)$. The $x$-coordinate is given by the integral formula $$\bar x = \frac{\ds\iiint_R xdV}{\ds\iiint_R dV}= \frac{\ds\int_{0}^{5}\int_0^7\int_{0}^{10-2x}(x)dzdydx}{\ds\int_{0}^{5}\int_0^7\int_{0}^{10-2x}1dzdydx}.$$ Compute this triple integral and simplify to show that $\bar x = \frac{5}{3}$.

- Modify the above formula to obtain integral formulas for both $\bar y$ and $\bar z$. Then state the values of $\bar y$ and $\bar z$, either by using facts we've already proven or by computing the integrals directly (use software).

- Draw the solid domain $D$ described by the bounds of the integral above. This is the solid satisfying the inequalities $0\leq x\leq 5$, $0\leq y\leq 7$, and $0\leq z\leq 10-2x$. Use the Mathematica code below to check that your plot is correct.

Task 15

This task provides you with a couple integrals that cannot be computed without first making some change. The first requires a change of order of integration. The second requires a change of coordinates.

- Compute by hand the iterated integral $$\ds \int_0^{2\sqrt{\pi}}\int_{y/2}^{\sqrt{\pi}} \sin(x^2)dxdy.$$ (Hint, you will need to swap the order of integration first.) Perform the computations by hand, and then check with Mathematica.

- The double integral $\ds\int_0^{\sqrt{2}}\int_{y}^{\sqrt{4-y^2}} e^{x^2+y^2}dxdy$ computes the mass of the region in the plane with density $\delta = e^{x^2+y^2}$ that is bounded by the curves $y=0$, $y=\sqrt{2}$, $x=y$, and $x=\sqrt{4-y^2}$.

- Draw the region described by these bounds. (Did you get a sector of a circle, something like a 1/8th of a pizza?)

- Give bounds of the form $?\leq \theta\leq ?$ and $?\leq r\leq ?$ that describe the region using polar coordinates (hint - the new bounds are all constants). Once you have the bounds, use Mathematica to verify that these bounds give the same region you drew before.

ClearAll[r, theta] outerB = {theta, , }; innerB = {r, , }; ParametricPlot[{r Cos[theta], r Sin[theta]}, outerB, innerB, Mesh -> {10, 0}] - Convert the Cartesian integral to an integral in polar coordinates (don't forget the Jacobian).

- Compute the integral by hand. Show your steps. Then verify you obtain the same result with Mathematica.

Self Check

I'll occasionally add relevant problems from OpenStax. As needed, spend a few minutes working on some exercises below. If you get stuck on a prep task, feel free to bring a solution to one of the textbook exercises to share.

- Pick some problems related to the topics we are discussing from the Text Book Practice page.

Task 16

This task has you practice setting up triple integrals and drawing 3D regions.

We already saw in a previous task that to draw the solid domain $D$ satisfying the inequalities $0\leq x\leq 5$, $0\leq y\leq 7$, and $0\leq z\leq 10-2x$, whose volume is given by $\ds\int_{0}^{5}\int_0^7\int_{0}^{10-2x}dzdydx$, we can use the Mathematica code below.

outerB = {x, 0, 5};

middleB = {y, 0, 7};

innerB = {z, 0, 10 - 2 x};

R = ParametricRegion[{x, y, z}, Evaluate[{outerB, middleB, innerB}]];

Region[R, Axes -> True, AxesLabel -> {x, y, z}, AxesOrigin -> {0, 0, 0}]

Integrate[1, outerB, middleB, innerB]

Complete the following.

- The iterated triple integral $\ds\int_{-1}^1\int_0^4\int_0^{y^2}dzdxdy$ gives the volume of the solid $D$ that lies under the surface $z=y^2$, above the $xy$-plane, and bounded by the planes $y=-1$, $y=1$, $x=0$, and $x=4$. Sketch this region first by hand, and then modify the Mathematica code above to check how you did.

- Set up an iterated triple integral that gives the volume of the solid in the first octant that is bounded by the coordinate planes ($x=0$, $y=0$, $z=0$), the plane $y+z=2$, and the surface $x=4-y^2$, using the order of integration $dxdzdy$. Make sure you sketch the region by hand, and then use Mathematica to check that your bounds are correct.

- Set up an integral to give the volume of the pyramid in the first octant that is below the planes $\ds\frac{x}{3}+\frac{z}{2}=1$ and $\ds\frac{y}{5}+\frac{z}{2}=1$. [Hint, don't let $z$ be the inside bound. Try an order such as $dydxdz$.] Once you have bounds for your integral, use the Mathematica to verify that your bounds do indeed draw the desired pyramid.

- (Optional Challenge) Set up an iterated triple integral that gives the volume of the region $D$ that is inside both right circular cylinders $x^2+z^2=1$ and $y^2+z^2=1$. Don't forget to draw the region.

Task 17

We've now found the mass and center-of-mass for straight wires, thin flat metal plates, and solid regions in space. Earlier in the semester we used $$s = \int_C ds = \int_C \left|\frac{d\vec r}{dt}\right|dt$$ to obtain the length of a thin wire lying on the curve $C$ with parametrization $\vec r(t)$. For such a wire, we use the differential $$\underbrace{ds}_{\text{little distance}} = \underbrace{ \left| \frac{d\vec r}{dt}\right| }_{ \text{speed} }\underbrace{dt}_{\text{little time}}$$ instead of $dx$ (little length in a straight rod), $dA$ (little area in a thin metal plate), or $dV$ (little volume in a solid). The differential $ds$ can replace $dx$, $dA$, or $dV$ in any of our previous formulas to help us determine, for a curved wire, the length, mass, center-of-mass, and more. This task has you set up several integrals that do this.

Consider a wire that lies along the curve $C$ with parametrization $\vec r(t) = (5\cos t,5\sin t)$ for $0\leq t\leq\pi$.

- Draw the curve, compute $\frac{d\vec r}{dt}$, and show that $ds = 5 dt$.

- Evaluate $\int_C ds$ to obtain the length of the wire. Since the curve is half a circle, the length you obtain from integration should be half the circumference of the circle.

- Assuming the density is constant, why do we know $\bar x=0$?

- Set up an integral formula for $\bar y$ and compute the integrals involved to obtain $\bar y$, showing your integration steps.

- If instead, the density is $\delta = xy^2+7$, then set up an integral formula to find $\bar x$. Use Mathematica to compute the integrals.

Task 18

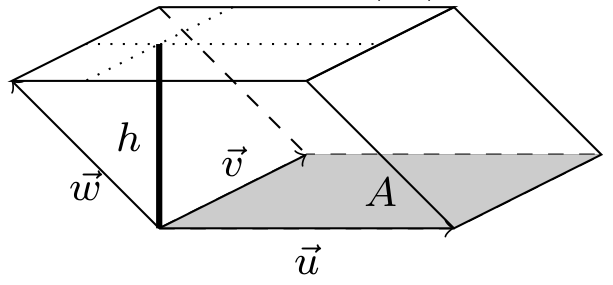

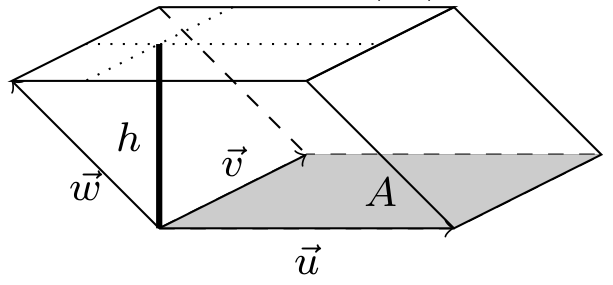

We already found the area of a parallelogram in the $xy$-plane. To use new coordinate systems in 3D, we need the volume of a parallelepiped formed by the three vectors $\vec u$, $\vec v$, and $\vec w$, shown in the image below.

We get the volume by obtaining the area $A$ of one face, multiplied by the distance $h$ between the base and the plane containing the opposing face. This means we need to (1) compute the area of a parallelogram in 3D, and then (2) obtain a formula for the distance between the opposing faces. In this task, we use the cross product and dot product to do both tasks.

- Let $\vec u = (a,b,c)$ and $\vec v = (d,e,f)$. Our goal is to find the area of a parallelogram whose edges are formed from these two vectors.

- Draw a picture that contains 2 vectors labeled $\vec u$ and $\vec v$. In that picture, include $\vec u_{\parallel \vec v}$ and $\vec u_{\perp\vec v}$. Explain why the area we seek is $A = |\vec u_{\perp\vec v}||\vec v|$.

- Use the following Mathematica code to compute the area. The Assumptions command below is needed to help Mathematica do some simplifications.

$Assumptions = a \[Element] Reals && b \[Element] Reals && c \[Element] Reals && d \[Element] Reals && e \[Element] Reals && f \[Element] Reals; u = {a, b, c}; v = {d, e, f}; uPerpv = u - Projection[u, v]; Norm[uPerpv]*Norm[v] // Simplify $Assumptions = Null - The magnitude of the cross product is $$|\vec u\times \vec v|= |(bf-ce, cd-af, ae-bd)| = \sqrt{(bf-ce)^2+ (cd-af)^2+ (ae-bd)^2}.$$ Show that the magnitude of the cross product and the area of the parallelogram (the value you obtained above) are the same. You can do this by hand, or with Mathematica. If you choose to use Mathematica, here is code for getting the magnitude of the cross product.

Norm[Cross[u, v]] // Simplify

- Find the area of the parallelogram formed by the two vectors $(1,2,3)$ and $(-3,1,4)$, by computing the magnitude of the cross product of these two vectors.

The cross product $\vec u\times\vec v$ of $\vec u$ and $\vec v$ is orthogonal to both $\vec u$ and $\vec v$. The magnitude of the cross product, so $|\vec u\times \vec v|$, is the area of the parallelogram formed by $\vec u$ and $\vec v$.

Now that we have a formula for the area of one face of a parallelepiped, we only need to find the distance between opposing faces to obtain the volume.

- Consider three vectors $\vec u$, $\vec v$, and $\vec w$ in $\mathbb{R}^3$. We will find the volume of the parallelepiped formed by these three vectors. Let the base of the parallelogram be the face formed by $\vec u$ and $\vec v$. The height $h$ is the distance between the plane that contains the base and the plane that contain the opposing side of the parallelepiped.

- Give a formula to compute the area of the base of the parallelogram. (What did the first part of this tasks help us learn?)

- Give a vector $\vec n$ that is normal to the base.

- Show that the height $h$ between opposing faces is $\frac{|\vec n\cdot \vec w|}{|\vec n|}$. Hint: review the projection formula.

- Use your work above to explain why the parallelepiped's volume is $$V=|(\vec u\times \vec v)\cdot \vec w|.$$

We call $(\vec u\times \vec v)\cdot \vec w$ the triple product of $\vec u$, $\vec v$, and $\vec w$. The volume of a parallelepiped formed by the three vectors is $V=|(\vec u\times \vec v)\cdot \vec w|$.

Task 19

A sphere of radius $a$ centered at the origin is described by the equation $x^2+y^2+z^2 = a^2$. A right circular cone whose tip is at the origin is given by $z=\sqrt{x^2+y^2}$ or $z^2=x^2+y^2$.

- Draw the surface $x^2+y^2+z^2 = a^2$ and then set up an iterated triple integral using Cartesian coordinates to compute the volume inside the sphere $x^2+y^2+z^2=a^2$.

- Draw the surface $z^2=x^2+y^2$ and then set up an iterated triple integral using Cartesian coordinates to compute the volume of the solid cone that lies above the cone $z^2=x^2+y^2$ and below the plane $z=h$.

- Use software to compute both integrals above. If software can't compute one of these integrals (the program hangs, never finishes, etc.), it's OK. These integrals are brutal, and we now learn some different coordinate systems that will make quick work of these integrals.

Task 20

In three dimensions, some common coordinate systems are cylindrical and spherical coordinates. In this task, for each of these coordinates systems, we'll (1) develop the change-of-coordinates formula, (2) compute the Jacobian using the triple product, and then (3) use the Jacobian to compute the volume of an object in this coordinate system.

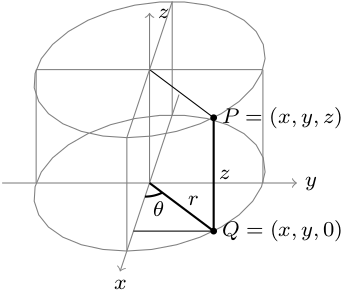

Let's first tackle cylindrical coordinates. Let $P=(x,y,z)$ be a point in space. This point lies on a cylinder of radius $r$, where the cylinder has the $z$ axis as its axis of symmetry. The height of the point is $z$ units up from the $xy$ plane. The point casts a shadow in the $xy$ plane at $Q=(x,y,0)$. The angle between the ray $\vec{Q}$ and the $x$-axis is $\theta$. See the image below.

- Explain why the equations for cylindrical coordinates are $$x=r\cos\theta, \quad y=r\sin\theta,\quad z=z.$$ [Hint: Compute the sine and cosine of $\theta$ in terms of $x$, $y$, and $r$, and then solve for $x$ and $y$.]

- Compute the Jacobian $\dfrac{\partial(x,y,z)}{\partial(r,\theta,z)}$ for cylindrical coordinates. The steps below are a guide, if needed.

- For cylindrical coordinates we have $x=r\cos\theta$, $y=r\sin\theta$, and $z=z$. Write the differential $d(x,y,z)$ as the linear combination of partial derivatives $$\begin{pmatrix}dx\\dy\\dz\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix}\cos\theta\\\sin\theta\\0\end{pmatrix}dr+\begin{pmatrix}?\\?\\?\end{pmatrix}d\theta+\begin{pmatrix}?\\?\\?\end{pmatrix}dz.$$

- Compute the volume of the parallelepiped formed by the three vectors (partial derivatives) above, using the triple product. Software can make quick work of this. Simplify your result to show that $\dfrac{\partial(x,y,z)}{\partial(r,\theta,z)} = |r|$.

- Consider the solid domain $D$ in space that lies inside the right circular cylinder $x^2+y^2=a^2$ (or $r=a$) for $0\leq z\leq h$. Start by drawing the domain $D$. The volume in cylindrical coordinates is given by the iterated integral $$V = \iiint_D dV = \ds\int_{0}^{2\pi}\int_{0}^{a}\int_{0}^{h}rdzdrd\theta.$$ Compute this integral by hand to obtain a familiar formula $V = \pi a^2 h$. The following Mathematica code can help you check your work.

outerB = {theta, 0, 2 Pi}; middleB = {r, 0, a}; innerB = {z, 0, h}; R = ParametricRegion[ {r Cos[theta], r Sin[theta], z}, Evaluate[{outerB, middleB /. a -> 5, innerB /. h -> 7}]]; Region[R, Axes -> True, AxesLabel -> {x, y, z}, AxesOrigin -> {0, 0, 0}] Integrate[r, outerB, middleB, innerB]

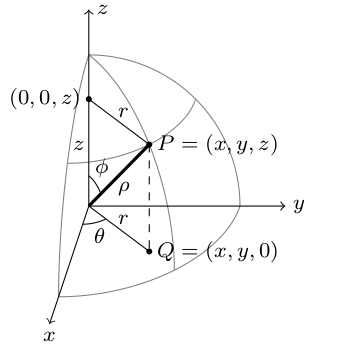

Now let's tackle spherical coordinates. Let $P=(x,y,z)$ be a point in space. This point lies on a sphere of radius $\rho$ ("rho"), where the sphere's center is at the origin $O=(0,0,0)$. The point casts a shadow in the $xy$ plane at $Q=(x,y,0)$. The angle between the ray $\vec{Q}$ and the $x$-axis is $\theta$, which some call the azimuth angle. The angle between the ray $\vec{P}$ and the $z$-axis is $\phi$ ("phi"), which some call the inclination angle, polar angle, or zenith angle. See the image below.

- Explain why the equations for spherical coordinates are $$x=\rho\sin\phi\cos\theta,\quad y=\rho\sin\phi\sin\theta,\quad z=\rho\cos\phi.$$ [Hint: Compute the sine and cosine of $\phi$ in terms of $\rho$, $r$, and $z$, and then solve for $r$ and $z$. Substitution into $x=r\cos\theta$ and $y=r\sin \theta$ will get the rest.]

- Compute the Jacobian $\dfrac{\partial(x,y,z)}{\partial(\rho,\phi,\theta)}$ for spherical coordinates. The steps below are a guide, if needed.

- For spherical coordinates we have $$x=\rho\sin\phi\cos\theta,\quad y=\rho\sin\phi\sin\theta,\quad z=\rho\cos\phi.$$ Write $d(x,y,z)$ as a linear combination of partial derivatives, so $$\begin{pmatrix}dx\\dy\\dz\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix}\sin\phi\cos\theta\\\sin\phi\sin\theta\\\cos\phi\end{pmatrix}d\rho+\begin{pmatrix}?\\?\\?\end{pmatrix}d\phi+\begin{pmatrix}?\\?\\?\end{pmatrix}d\theta.$$

- Compute the volume of the parallelepiped formed by the three vectors (partial derivatives) above. Software can make quick work of this. You can do it all by hand, but you'll have to use a Pythagorean identity several times to complete the simplification. Simplify your result to show that $\frac{\partial(x,y,z)}{\partial(\rho,\phi,\theta)} = |\rho^2\sin\phi|$.

- Consider the solid domain $D$ in space that lies inside the sphere $x^2+y^2+z^2=a^2$ (or $\rho=a$). Start by drawing the domain $D$. The volume in spherical coordinates is given by the iterated integral $$V = \iiint_D dV = \ds\int_{0}^{2\pi}\int_{0}^{\pi}\int_{0}^{a}\rho^2\sin\phi d\rho d\phi d\theta.$$ Compute this integral to obtain a familiar formula $V = \frac{4}{3}\pi a^3$. The following Mathematica code can help you check your work.

outerB = {theta, 0, 2 Pi}; middleB = {phi, 0, Pi}; innerB = {rho, 0, a}; R = ParametricRegion[ {rho Sin[phi] Cos[theta], rho Sin[phi] Sin[theta], rho Cos[phi]}, Evaluate[{outerB, middleB, innerB /. a -> 5}]]; Region[R, Axes -> True, AxesLabel -> {x, y, z}, AxesOrigin -> {0, 0, 0}] Integrate[rho^2 Sin[phi], outerB, middleB, innerB]

There is some disagreement between different scientific fields about the notation for spherical coordinates. In some fields (like physics), $\phi$ represents the azimuth angle and $\theta$ represents the inclination angle, swapped from what we see here. In some fields, like geography, instead of the inclination angle, the elevation angle is given --- the angle from the $xy$-plane (lines of latitude are from the elevation angle). Additionally, sometimes the coordinates are written in a different order. You should always check the notation for spherical coordinates before communicating to others with them. As long as you have an agreed upon convention, it doesn't really matter how you denote them. See Wikipedia or MathWorld for a discussion of conventions in different disciplines.

Task 21

This task has you practice using spherical and cylindrical coordinates. Mathematica's ParametricRegion[] command allows us to plot a region, using any coordinate system, which is extremely useful for visualizing regions defined by bounds of an integral. As an example, the code below visualizes the region whose volume is given by the cylindrical coordinate iterated triple integral $$\int_{1}^{3}\int_{\pi/2}^{2\pi}\int_{0}^{r}rdz d\theta dr,$$ and then computes the triple integral.

coordinates = {r Cos[theta], r Sin[theta], z};

outerB = {r, 1, 3}

middleB = {theta, Pi/2, 2 Pi}

innerB = {z, 0, r}

R = ParametricRegion[coordinates, Evaluate[{outerB, middleB, innerB}]];

Region[R, Axes -> True, AxesLabel -> {x, y, z}, AxesOrigin -> {0, 0, 0}]

Integrate[r, outerB, middleB, innerB]

To compute integrals in spherical coordinates, we just update the change-of-coordinates and bounds. Here's code to plot the region whose volume is given by the spherical coordinate iterated triple integral $$\ds \int_{0}^{\pi}\int_{\pi/6}^{\pi/3}\int_{1}^{3}\rho^2\sin\phi d\rho d\phi d\theta.$$

coordinates = {rho Sin[phi] Cos[theta], rho Sin[phi] Sin[theta], rho Cos[phi]};

outerB = {theta, 0, Pi/2}

middleB = {phi, Pi/6, Pi/3}

innerB = {rho, 1, 3}

R = ParametricRegion[coordinates, Evaluate[{outerB, middleB, innerB}]];

Region[R, Axes -> True, AxesLabel -> {x, y, z}, AxesOrigin -> {0, 0, 0}]

Integrate[r, outerB, middleB, innerB]

- Consider the solid domain $D$ in space which is above the cone $z=\sqrt{x^2+y^2}$ and below the paraboloid $z=6-x^2-y^2$.

- Sketch the region by hand.

- Explain why an equation of the cone in cylindrical coordinates is $z=r$. Then obtain an equation of the paraboloid in cylindrical coordinates.

- Use cylindrical coordinates to set up an iterated triple integral that would give the volume of the region. You'll need to find where the surfaces intersect, as their intersection will help you determine the appropriate bounds. Use Mathematica to verify that the bounds you gave do indeed produce the correct region.

- By symmetry, it should be clear that for the centroid of this region, we have $\bar x = \bar y = 0$. Set up a formula involving iterated triple integrals that would give $\bar z$ for this solid, and then use software to compute $\bar z$.

- Consider the solid domain $D$ in space that lies below the cone $z=\sqrt{x^2+y^2}$, above the $xy$-plane, and inside the sphere $x^2+y^2+z^2=25$.

- Provide a sketch of the domain $D$.

- Explain why an equation of the cone in spherical coordinates is $\phi = \pi/4$. Then given an equation of the sphere in spherical coordinates.

- Set up an integral in spherical coordinates that gives the volume of $D$. Use Mathematica to verify that the bounds you gave do indeed produce the correct region.

- Set up an integral in spherical coordinates that would give the $z$-coordinate of the centroid of $D$.

Task 22

- Consider the region $R$ in space satisfying $0\leq x-y\leq 4$ and $1\leq 2x+y\leq 3$. We wish to evaluate the integral $\ds\iint_R xy dA$.

- Draw the region $R$.

- Using the change-of-coordinates $u=x-y$ and $v=2x+y$, compute the Jacobian $\frac{\partial(u,v)}{\partial (x,y)}$.

- Find $x$ and $y$ in terms of $u$ and $v$.

- Use this change-of-coordinates to compute $\ds\iint_R xy dA$ by first setting up an appropriate iterated integral of the form $\ds \int_{?}^{?}\int_{?}^{?}?dudv$.

- Consider the solid domain $D$ inside the ellipsoid $\ds\frac{x^2}{a^2}+\frac{y^2}{b^2}+\frac{z^2}{c^2}=1$, for some positive constants $a$, $b$, and $c$. You can use $a=5$, $b=7$, and $c=11$ if needed.

- Draw the solid domain $D$.

- Using the change-of-coordinates $x = a u \sin v \cos w$, $y = b u \sin v \sin w$, $x = c u \cos v$, with all three of $a$, $b$, and $c$ positive, compute the Jacobian $\frac{\partial (x,y,z)}{\partial (u,v,w)}$. Feel free to use software to help you. [Check: This is very similar to spherical coordinates, and could be called ellipsoidal coordinates. The Jacobian is $|abcu^2\sin v|$. ]

- Set up an iterated integral using $uvw$-coordinates to compute the volume of $D$. Then compute the integral to obtain $V = \frac{4}{3}\pi abc$.

- Set up an iterated integral using $uvw$-coordinates to show that $\bar z = \frac{3c}{8}$ for the region inside the ellipsoid that is above the $xy$-plane.

When you've got a guess for the bounds of your integral, use the code below to check your solution.

outerB = {u, ,};

middleB = {v, ,};

innerB = {w, ,};

coordinates = {5 u Sin[v] Cos[w], 7 u Sin[v] Sin[w], 11 u Cos[v]}

R = ParametricRegion[coordinates, Evaluate[{outerB, middleB, innerB}]];

Region[R, Axes -> True, AxesLabel -> {x, y, z}, AxesOrigin -> {0, 0, 0}]

Task 23

- Consider the region that lies below the $z$-axis and between 2 spheres of radii $a$ and $b$ with $a<b$. The image below shows such a region where the inner radius is $a=3$, and the outer radius is $b=5$.

- Set up an iterated triple integral in spherical coordinates to compute the volume of this region. Use Mathematica to verify you have the correct bounds.

- Set up an iterated triple integral formula to compute the $z$-coordinate of the centroid (symmetry gives us $\bar x = \bar y = 0$).

- If the temperature at points in this region is given by $T(x,y,z) = x+3$, then set up an iterated triple integral formula that would give the average temperature of the region.

- A metal casing lies inside the cylinder $x^2+y^2=4$, outside the cylinder $x^2+y^2=1$, below the paraboloid $z=9-x^2-y^2$, and above the plane $z=0$. The region is shown below, where one quarter of the region was removed so you can see the hollow interior.

- Set up an iterated integral in cylindrical coordinates to compute the volume of the casing. Use Mathematica to verify you have the correct bounds.

- The casing is made of a composite material and the density of the casing is more dense the further from the center. The density is given by $\delta(x,y,z) = x^2+y^2$. Set up an iterated triple integral formula to compute the $z$-coordinate of the center-of-mass of the casing.

If the ParametricRegion[] command is extremely slow on your computer, then here's an alternative. The code plots the six surfaces defined by your bounds and requires very minimal processing (it works fast).

plotRegion3D[cs_, ob_, mb_, ib_] :=

Show[{{ParametricPlot3D[Evaluate[Table[cs /. (ib[[1]] -> ib[[i]]), {i, 2, 3}], ob, mb], AxesLabel -> {x, y, z}, Mesh -> {15, 1}],

ParametricPlot3D[Evaluate[Table[(cs /. (ib[[1]] -> (ib[[2]] (1 - s) + ib[[3]] s))) /. (mb[[1]] -> mb[[i]]), {i, 2, 3}], ob], {s, 0, 1}, PlotStyle -> {Red, Blue}, Mesh -> {15, 0}],

ParametricPlot3D[Evaluate[Table[(cs /. (ib[[1]] -> (ib[[2]] (1 - s) + ib[[3]] s))) /. (mb[[1]] -> (mb[[2]] (1 - t) + mb[[3]] t)) /. (ob[[1]] -> ob[[i]]), {i, 2, 3}]], {t, 0, 1}, {s, 0, 1}, PlotStyle -> Green, Mesh -> {0, 0}]}}, PlotRange -> All]

coordinates = {r Cos[theta], r Sin[theta], z}

plotRegion3D[coordinates, {r, 1, 3}, {theta, Pi/2, 2 Pi}, {z, 0, r}]

coordinates = {rho Sin[phi] Cos[theta], rho Sin[phi] Sin[theta], rho Cos[phi]}

plotRegion3D[coordinates, {theta, 0, Pi/2}, {phi, Pi/6, Pi/3}, {rho, 1, 3}]

Task 24

- Consider the integral $\ds \int_{0}^{4}\int_{0}^{4-x} e^{(x+y)^2}dydx$ and the change-of-coordinates $u=x$, $v=x+y$.

- Solve for $x$ and $y$ in terms of $u$ and $v$, and then compute $\frac{\partial(x,y)}{\partial(u,v)}$.

- Set up the corresponding iterated integral using the order $dvdu$. Then set up the corresponding integral using the order $dudv$.

- Compute the simpler of the two integrals you just set up.

- Consider the integral $\ds \iint_R xy dA$ for the region $R$ that lies inside the triangle with vertices $(0,0)$, $(2,4)$, and $(3,-3)$. Notice that two of the edges of the triangle lie on the lines $y=2x$ and $y=-x$, which means we'll use the change-of-coordinates $u=2x-y$, $v=x+y$.

- Sketch the region $R$ in the $xy$-plane. Then sketch the corresponding region in the $uv$-plane (you should obtain a triangle).

- Set up an iterated integral using $uv$-coordinates to compute $\ds \iint_R xy dA$.

- Compute the integral.

Task 25

The shell method and disc method are two methods for computing the volume of a solid of revolution using a single integral. As a solid of revolution has volume, then a triple integral will give the volume, provided we can set up appropriate bounds. In this task, we'll see that the only difference between the shell and disc methods are the order in which a triple integral is done. If you've forgotten (which is completely normal), here's a reminder.

- The shell-method computes volumes with $$V = \int dV = \int_a^b \underbrace{(2\pi r)(\text{height of shell at $r$})}_{\text{shell surface area = (circumference)(height)}} \underbrace{dr}_{\text{shell thickness}}.$$

- The disc-method computes volumes with $$V = \int dV =\int_a^b \underbrace{\pi (\text{radius of disc at height $z$})^2}_{\text{area of disc at height $z$}} \underbrace{dz}_{\text{little height}}.$$

- Consider the solid region in space that is bounded above by $z=9-x^2-y^2$ (so $z=9-r^2$) and below by the $xy$-plane. In Cartesian coordinates, the volume of this region is given by $$\int_{-3}^{3}\int_{-\sqrt{9-x^2}}^{\sqrt{9-x^2}}\int_{0}^{9-x^2-y^2}dzdydx.$$ This region is formed by taking the region under the parabola $z=9-r^2$ (above the plane $z=0$) and revolving it about the $z$-axis.

- Set up a triple integral in cylindrical coordinates to compute the volume of this solid using the order $d\theta dzdr$.

- Compute the two inside integrals and simplify to show that $V = \int_{0}^{3} 2\pi r (9-r^2) dr$.

- Set up a triple integral in cylindrical coordinates to compute the volume of this solid using the order $d\theta drdz$. You will end up with $r=\sqrt{9-z}$ as one of the bounds.

- Compute the two inside integrals and simplify to show that $V = \int_{0}^{9} \pi (\sqrt{9-z})^2 dz$.

- Which order above uses the shell method, and which uses the disc method?

- Consider the region in space that satisfies $0\leq a\leq r\leq b$ with $g(r)\leq z\leq f(r)$.

- Construct a sketch of such a region. You get to pick and illustrate what $a$, $b$, $g(r)$, and $f(r)$ mean.

- Set up a triple integral in cylindrical coordinates to compute the volume of this solid using the order $d\theta dzdr$.

- Compute the two inside integrals to obtain a formula for the volume that involves a single integral in terms of $r$.

- Consider the region in space that satisfies $c\leq z\leq d$ with $0\leq g(z)\leq r\leq f(z)$.

- Construct a sketch of such a region. You get to pick and illustrate what $c$, $d$, $g(z)$, and $f(z)$ mean.

- Set up a triple integral in cylindrical coordinates to compute the volume of this solid using the order $d\theta drdz$.

- Compute the two inside integrals to obtain a formula for the volume that involves a single integral in terms of $z$.

Task 26

When we use double integrals to find centroids, the formulas for the centroid are similar for both $\bar x$ and $\bar y$. In other courses, you may see the formulas that appear in this task, because the ideas are presented without requiring knowledge of double integrals. Integrating the inside integral from the double integral formula gives the single variable formulas that you'll find in other courses.

Let $R$ be the region in the plane with $a\leq x\leq b$ and $g(x)\leq y\leq f(x)$.

- Set up an iterated integral to compute the area of $R$. Then compute the inside integral. You should obtain a familiar formula from first-semester calculus.

- Set up an iterated integral formula to compute $\bar x$ for the centroid. By computing the inside integrals, show that $$\ds\bar x = \frac{\int_a^b x (f-g)dx}{\int_a^b (f-g)dx}.$$

- If the density depends only on $x$, so $\delta = \delta (x)$, set up an iterated integral formula to compute $\bar y$ for the center of mass. Compute the inside integral and show that $$\ds\bar y = \frac{\ds\int_a^b \frac{1}{2}(f^2-g^2)\delta(x)dx}{\ds\int_a^b (f-g)\delta(x)dx} = \frac{\ds\int_a^b \overbrace{\frac{(f+g)}{2}}^{\tilde y}\overbrace{\delta(x)\underbrace{(f-g)dx}_{dA}}^{dm}}{\text{mass}}.$$

In class, fell free to ask and we'll analyze the integral formula above and show how you can set this up as a single integral using geometric reasoning. We'll discuss the quantities $\tilde y$, $dm$, and $dA$, as appropriate.

Task 27

We've been working with rods, wires, thin plates, and solid domains. For example, we could work with a circular wire, or a circular disc, or a ball. How do the centroid formulas change in each setting? This task has us examine these three setting, set up the corresponding integrals, use software to solve them, and then compare the locations of the centroids.

Consider the curve $C$ that is the upper half of the circle $x^2+y^2 = 49$, the region $R$ that lies above $y=0$ and inside the circle $x^2+y^2=49$, and the solid domain $D$ that lies inside the sphere $x^2+y^2+z^2=49$ and satisfies $y\geq 0$. Because of symmetry, for each region it is clear that $\bar x=\bar z=0$.

- Set up an integral formula to compute $\bar y$ for the curve $C$. [Hint: You'll need a parametrization.]

- Set up an integral formula to compute $\bar y$ for the region $R$. [You can use Cartesian coordinates or polar coordinates.]

- Set up an integral formula to compute $\bar y$ for the domain $D$.

- Use software to compute all three integral formulas above, obtaining an exact value for the answer (not a numerical approximation).

- For each object, state a general formulas for $\bar y$ if the radius is $a$ (not $7$).

Task 28

Pick a few regions from Wikipedia's List of Centroids and then set up and compute (with software) iterated integral formulas to find the centroids from that list. Try doing some that are 2D, and some that are 3D.