- I-Learn, Class Pictures, Learning Targets, Text Book Practice

- Prep Tasks: Unit 1 - Motion, Unit 2 - Derivatives, Unit 3 - Integration, Unit 4 - Vector Calculus

Day 33 - Prep

Task 33.1

Polar coordinates is one type of new coordinate system, in particular this coordinate systems helps compute double integrals for planar regions that have some kind of rotational symmetry. We've actually been using change-of-coordinates since first semester calculus, every time we perform a substitution to complete an integral. What we'll do in this task is look at two changes-of-coordinates, one which stretches lengths, and the other which stretches areas.

- Consider the integral $\ds\int_{-1}^{2} e^{-3x}\, dx$.

- To complete this integral we use the substitution $u=-3x$. Solve for $x$ and compute the differential $dx$.

- Perform the substitution, filling in the missing parts of $$\int_{x=-1}^{x=2} e^{-3x}\, dx = \int_{u=?}^{u=?} e^{u}? du.$$ Note that when a definite integral ends with $du$, the bounds should be in terms of $u$. To find the $u$ bounds, just ask, "If $x=-1$, then $u=?$" Don't spend any time completing the integral, rather just focus on completing the substitution above.

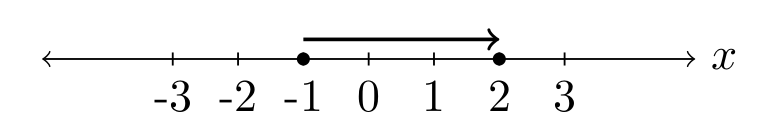

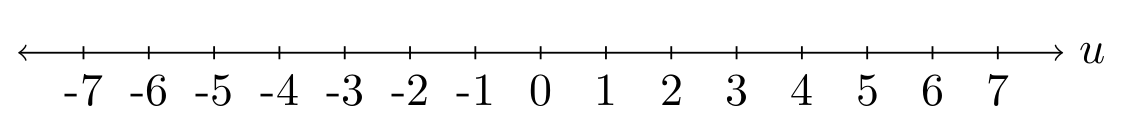

- The $x$ values range from $-1$ to $2$. This is a directed interval whose width is 3 units, pointing from left to right along the $x$-axis (shown below). Our substitution $u=-3x$ transforms this directed interval into a different directed interval along the $u$-axis. Draw the transformed interval on the $u$-axis below.

- How long is the new interval along the $u$-axis? What does your differential equation $dx=-\frac{1}{3}du$ have to do with this problem? What does the negative sign do?

Above we showed that the differential equation $dx = \frac{dx}{du}du$ tells us how to relate lengths along the $u$-axis to lengths along the $x$-axis. We could think of the number $\frac{dx}{du}$ as a length stretch factor. Let's now examine a two dimensional change-of-coordinates, and connect areas in the $uv$-plane to areas in the $xy$-plane.

- Consider the change-of-coordinates $x=u-v$ and $y=u+v$, which we could also write as the coordinate transformation $\vec T(u,v) = (u-v,u+v)$.

- In the table below, you're given several $(u,v)$ points. Find the corresponding $(x,y)$ pair. $$ \begin{array}{|c|c|c|} \text{Name}&(u,v)&(x,y)\\\hline A&(0,0)&(0,0)\\ B&(1,0)&(1-0,1+0) = (1,1)\\ C&(0,1)&(0-1,0+1) = (-1,1)\\ D&(1,1)&\\ E&(3,3)&\\ F&(2,4)&\\ G&(-2,4)&\\ \end{array}$$

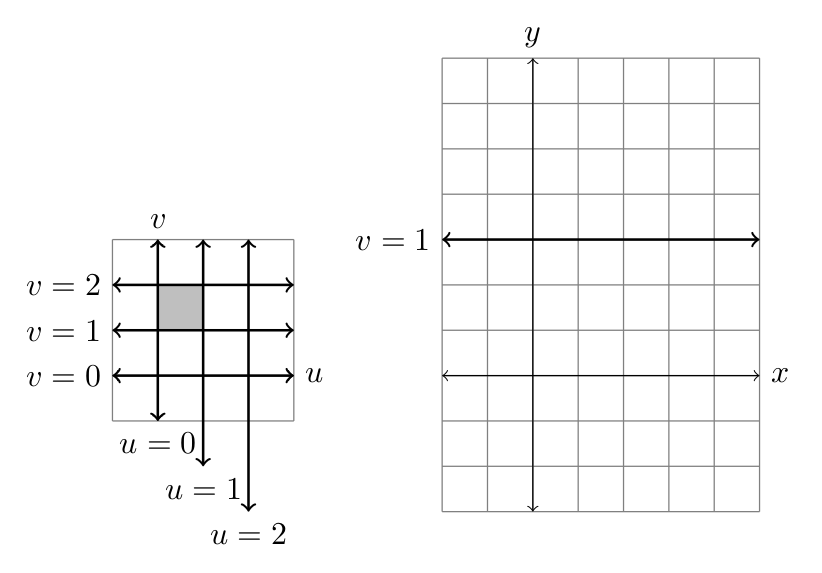

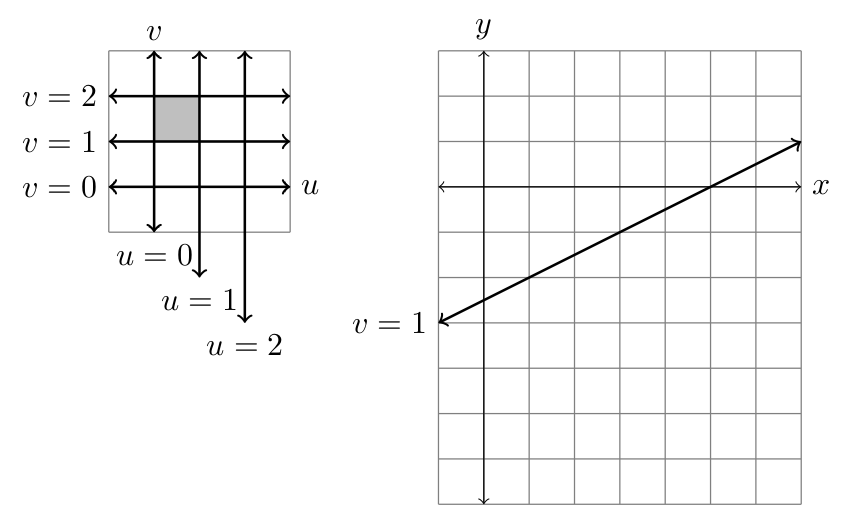

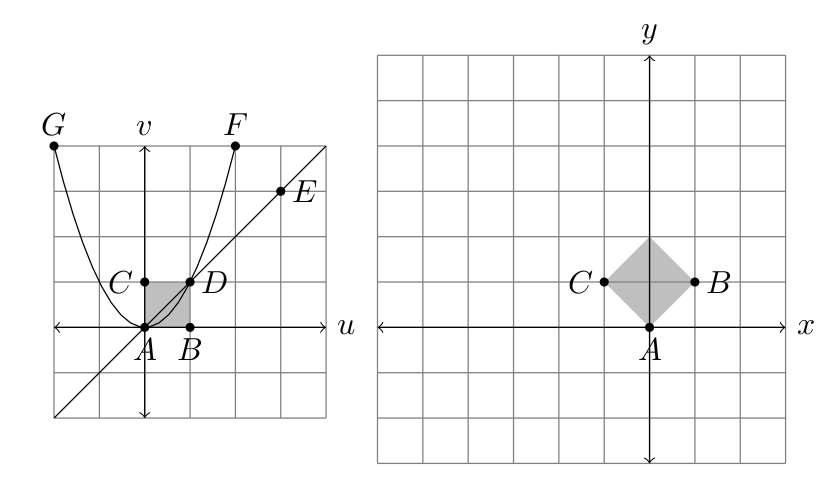

- There are two graphs below. One is a plot in the $uv$-plane of the points from the table, along with the parabola $v=u^2$, the line $v=u$, and the shaded box whose corners are the first four points. Complete a similar plot in the $xy$-plane by adding the remaining points, and then connect the points in your $xy$ plot to show how the parabola, line, and shaded box (done for you) transform because of this change-of-coordinates. How would you describe what this change-of-coordinates is doing?

- The following Mathematica code allows you to draw any region from the $uv$-plane in the $xy$ plane. You can use it to check your work (as well as adapt the code to work with ANY new coordinate system).

R1 = ParametricRegion[{{u - v, u + v}, 0 <= u <= 1 && 0 <= v <= 1}, {u, v}]; Region[R1, Axes -> True, AxesLabel -> {x, y}] R2 = ParametricRegion[{{u - v, u + v}, v == u^2}, {{u, -2, 2}, v}]; Region[R2, Axes -> True, AxesLabel -> {x, y}]

- The differential of $x$ is $dx = du-dv$. Obtain a similar formula for the differential $dy$. Then write your answer as the vector equation (linear combination) $$\begin{pmatrix}dx\\dy\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 1\\ ?\end{pmatrix}du+\begin{pmatrix}-1\\?\end{pmatrix}dv.$$

- How are areas in the $uv$-plane related to areas in the $xy$-plane? In particular, the area of the 1 by 1 box in the $uv$ plane is 1. What is the area of the shaded region in the $xy$-plane. By how much are we stretching areas when we change from $uv$ to $xy$ coordinates (what's the "area stretch factor")?

The area stretch factor above is called a "Jacobian". We'll soon have quick way to compute a Jacobian, which will result from finding the area of a parallelogram (the next task).

Task 33.2

We need a quick way to compute the area of a parallelogram. In this task, we'll prove the following theorem and then use it in a few specific examples.

The area $A$ of a parallelogram whose edges are the two vectors $\vec u= (a,b)$ and $\vec v = (c,d)$ is given by $A=|ad-bc|$.

- Suppose a parallelogram has edges that are parallel to the vectors $\vec u=(a,b)$ and $\vec v=(c,d)$. Prove that the area of this parallelogram is given by $|ad-bc|$. If you want some help, here are some steps you can follow:

- Draw a generic parallelogram. Label one corner the origin, and then the two connecting edges are the vectors $\vec u = (a,b)$ and $\vec v=(c,d)$.

- Add to your picture (1) the projection of $\vec u$ onto $\vec v$ (so $\vec u_{\parallel \vec v}$) and (2) the component of $\vec u$ that is orthogonal to $\vec v$ (so $\vec u_{\perp \vec v}$).

- Explain why the area is $A = |\vec v||\vec u_{\perp \vec v}|$.

- Use Mathematica to perform the computations, and then explain why the result given is equal to $|ad-bc|$.

u = {a, b}; v = {c, d}; uPerpv = u - Projection[u, v]; Norm[uPerpv]*Norm[v] // FullSimplify

- Whether you are able to complete the proof above or not, let's practice using the result to compute areas of parallelogram (and triangles). Use the area formula $|ad-bc|$ to compute the requested areas below.

- A parallelogram has vertices $(0,0)$, $(-2,5)$, $(3,4)$, and $(1,9)$. Find its area.

- Find the area of the triangle with vertices $(0,0)$, $(-2,5)$, and $(3,4)$.

- Find the area of the triangle with vertices $(-3,1)$, $(-2,5)$, and $(3,4)$. [You'll need to give vectors $\vec u$ and $\vec v$ that form the edges of a parallelogram.]

Task 33.3

Recall that the gradient of a function $f$ is the quantity $$\vec \nabla f = \left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x},\frac{\partial f}{\partial y},\frac{\partial f}{\partial z} \right) = \left(\frac{\partial }{\partial x},\frac{\partial }{\partial y},\frac{\partial }{\partial z} \right)f ,$$ where in the last expression we let $\vec \nabla = \left(\frac{\partial }{\partial x},\frac{\partial }{\partial y},\frac{\partial }{\partial z} \right)$ and then treat $\vec \nabla f$ as a "vector" $\vec \nabla$ times a scalar $f$. The quantity $\vec \nabla = \left(\frac{\partial }{\partial x},\frac{\partial }{\partial y},\frac{\partial }{\partial z} \right)$ is an example of something we call an "operator," something that operates on functions.

An operator is a function whose input is a function itself. This allows us to say "operator on functions" instead of "function of functions."

We've already encountered several operators before this class. For example, the derivative operator $\frac{d}{dx}$ from first semester calculus takes a function such as $f(x) = x^2$ and returns a new function $\frac{d}{dx}f = 2x$. The integral operator $\int_a^b f dx$ takes a function $f$ and return a real number. The gradient operator takes a function $f$ and returns a vector of functions $\vec \nabla f = (f_x,f_y,f_z)$. This is just 3 examples of operators. Here are two more.

Consider the vector field $\vec F(x,y,z) = (M,N,P)$, where $M$, $N$, and $P$ are functions of $x$, $y$, and $z$.

- The divergence of $\vec F$ is the scalar quantity $$ \begin{align*} \text{div}(\vec F) &= \vec \nabla \cdot \vec F \\ &= \left(\frac{\partial }{\partial x},\frac{\partial }{\partial y},\frac{\partial }{\partial z} \right)\cdot \left(M,N,P\right) \\ &= \frac{\partial M}{\partial x}+\frac{\partial N}{\partial y}+\frac{\partial P}{\partial z}\\ &= M_x+N_y+P_z . \end{align*} $$

- The curl of $\vec F$ is the vector quantity $$ \begin{align*} \text{curl}(\vec F) &= \vec \nabla \times \vec F \\ &= \left(\frac{\partial }{\partial x},\frac{\partial }{\partial y},\frac{\partial }{\partial z} \right)\times \left(M,N,P\right) \\ &= \left(\frac{\partial P}{\partial y}-\frac{\partial N}{\partial z},\frac{\partial M}{\partial z}-\frac{\partial P}{\partial x},\frac{\partial N}{\partial x}-\frac{\partial M}{\partial y}\right) \\ &= \left(P_y-N_z,M_z-P_x,N_x-M_y\right) . \end{align*} $$

We will often say "del dot F" for the divergence of $\vec F$, and "del cross F" for the curl of $\vec F$.

Use the definitions above to compute the divergence and curl of each vector field below. Then compute the derivative (which will be a 3 by 3 matrix). Finish by checking your work with Mathematica (code for doing so is provided below). If you see any relationships worth mentioning, articulate them in your work.

- $\vec F = (2x, 3y^2, e^z)$

- $\vec F = (-3y, 3x, 5z)$

- $\vec F = (z-3y, 3x, -x)$

In class, we'll talk about the physical meaning of each result above.

The code below computes the derivative, divergence, and curl of the vector field $\vec F = (x^2 y, x y z, 3 x + 4 z)$.

F = {x^2 y, x y z, 3 x + 4 z }

D[F, {{x, y, z}}] // MatrixForm

Div[F, {x, y, z}]

Curl[F, {x, y, z}]

Task 33.4

Pick some problems related to the topics we are discussing from the Text Book Practice page.

Day 33 - In class

Brain Gains (Rapid Recall, Jivin' Generation)

- Consider the change-of-coordinates given by $x = 2u+v$ and $y=u-2v$. Draw the region in the $xy$-plane given by $1\leq u\leq 2$ and $0\leq v\leq 1$. Suggestion: first complete the table below.

$$\begin{array}{c|c} (u,v)&(x,y)\\\hline (1,0)&(2+0,1-0) = (2,1)\\ (1,1)&(2+1,1-2) = (3,-1)\\ (2,0)&\\ (2,1)& \end{array}$$

Solution

Here's the region, with Mathematica code.

R = ParametricRegion[{2 u + v, u - 2 v}, {{u, 1, 2}, {v, 0, 1}}];

Region[R, Axes -> True, AxesLabel -> {x, y}, AxesOrigin -> {0, 0}]

- Compute the differential $(dx,dy)$ for the change-of-coordinates given by $x = 2u+v$ and $y=u-2v$. Write your answer as a linear combination.

Solution

We have $dx = 2du+1dv$ and $dy = du-2dv$. This gives $$\begin{pmatrix}dx\\dy\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix}2\\1\end{pmatrix}du + \begin{pmatrix}1\\-2\end{pmatrix}dv.$$

- State the area of a parallelogram whose edges are the vectors $(a,b)$ and $(c,d)$.

Solution

The prep had you show that the area is $A = |ad-bc|$.

- State the area of a parallelogram whose edges are the vectors $(2,1)$ and $(1,-2)$, so the vectors from the differential of the change-of-coordinates $x = 2u+v$, $y=u-2v$. We call this the Jacobian of the change-of-coordinates given by $x = 2u+v$ and $y=u-2v$, written $\ds\frac{\partial(x,y)}{\partial(u,v)}$.

Solution

We have $$\frac{\partial(x,y)}{\partial(u,v)}= A = |ad-bc| = |(2)(-2)-(1)(1)|=|-5|=5.$$

- Recall the derivative of a vector field $\vec F(x,y,z)=(M,N,P)$ is the 3 by 3 matrix $$\ds D\vec F(x,y,z) = \begin{bmatrix}\dfrac{\partial \vec F}{\partial x}&\dfrac{\partial \vec F}{\partial y}&\dfrac{\partial \vec F}{\partial z}\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}M_x&M_y&M_z\\N_x&N_y&N_z\\P_x&P_y&P_z\end{bmatrix}$$ Compute the derivative $D\vec F(x,y,z)$ of the vector field $\vec F(x,y,z) = (3x+4yz, 5x^2+2z, xyz)$.

Solution

We can use Mathematica to check.

F = {3 x + 4 y z, 5 x^2 + 2 z, x y z}

D[F, {{x, y, z}}] // MatrixForm

- The divergence of a vector field $\vec F(x,y,z) = (M,N,P)$ is $$\begin{align*} \text{div}(\vec F) &= \vec \nabla \cdot \vec F \\ &= \left(\frac{\partial }{\partial x},\frac{\partial }{\partial y},\frac{\partial }{\partial z} \right)\cdot \left(M,N,P\right) \\ &= \frac{\partial M}{\partial x}+\frac{\partial N}{\partial y}+\frac{\partial P}{\partial z}\\ &= M_x+N_y+P_z . \end{align*}$$ Compute the divergence of the vector field $\vec F(x,y,z) = (3x+4yz, 5x^2+2z, xyz)$.

Solution

We can use Mathematica to check our work.

F = {3 x + 4 y z, 5 x^2 + 2 z, x y z}

Div[F, {x, y, z}]

- The curl of a vector field $\vec F(x,y,z) = (M,N,P)$ is $$\begin{align*} \text{curl}(\vec F) &= \vec \nabla \times \vec F \\ &= \left(\frac{\partial }{\partial x},\frac{\partial }{\partial y},\frac{\partial }{\partial z} \right)\times \left(M,N,P\right) \\ &= \left(\frac{\partial P}{\partial y}-\frac{\partial N}{\partial z},\frac{\partial M}{\partial z}-\frac{\partial P}{\partial x},\frac{\partial N}{\partial x}-\frac{\partial M}{\partial y}\right) \\ &= \left(P_y-N_z,M_z-P_x,N_x-M_y\right) . \end{align*}$$ Compute the curl of the vector field $\vec F(x,y,z) = (3x+4yz, 5x^2+2z, xyz)$.

Solution

We can use Mathematica to check our work.

F = {3 x + 4 y z, 5 x^2 + 2 z, x y z}

Curl[F, {x, y, z}]

Group Problems

- Find the area of the parallelogram whose vertices are $(0,0)$, $(2,4)$, $(-3,1)$, and $(-1,5)$. [Check: 14]

- Then find the area of the triangle who vertices are $(0,0)$, $(2,4)$, and $(-3,1)$. (How is the triangle related to the parallelogram?)

- Now find the area of the triangle who vertices are $(2,4)$, $(-3,1)$, and $(-1,5)$.

- Now find the area of the triangle who vertices are $(0,0)$, $(-3,1)$, and $(-1,5)$. (If you got the same answer for the last 3 questions, then hooray!)

- Find the area of the triangle whose vertices are $(-2,1)$, $(3,4)$, and $(1,7)$. [Check: 21/2]

- For the vector field $\vec F = (xyz, 3x^2+4y, 2x+3y+4z)$, compute the derivative, the divergence, and the curl. Use Mathematica to check your work.

- Consider the change of coordinates given by $x = 3u+2v$ and $y=u-4v$.

- Draw the region in the $xy$-plane given by $0\leq u\leq 1$ and $0\leq v\leq 1$. You can use the Mathematica code from above to check your answer.

- Compute the area of the region you just drew (the region should be a parallelogram).

- Compute the differential of the change-of-coordinates, and write it in the form $$\begin{pmatrix}dx\\dy\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} ?\\ ?\end{pmatrix}du+\begin{pmatrix}?\\?\end{pmatrix}dv.$$

- State the Jacobian $\ds\frac{\partial(x,y)}{\partial(u,v)}$.

- Pick values for $a,b,c,d$ in the change-of-coordinates $x = au+bv$, $y=cu+dv$.

- Draw the region in the $xy$-plane given by $0\leq u\leq 1$ and $0\leq v\leq 1$. You can use the Mathematica code from above to check your answer.

- Compute the area of the region you just drew (the region should be a parallelogram).

- Compute the differential of the change-of-coordinates, and write it in the form $$\begin{pmatrix}dx\\dy\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} ?\\ ?\end{pmatrix}du+\begin{pmatrix}?\\?\end{pmatrix}dv.$$

- State the Jacobian $\ds\frac{\partial(x,y)}{\partial(u,v)}$.

- Pick your own vector field $\vec F(x,y,z) = (?, ?, ?)$, compute the derivative, the divergence, and the curl. Use Mathematica to check your work.

F = {x^2 y, x y z, 3 x + 4 z } D[F, {{x, y, z}}] // MatrixForm Div[F, {x, y, z}] Curl[F, {x, y, z}]

Day 34 - Prep

Task 34.1

It's time to focus on how area is changed when we perform a change-of-coordinates. We'll see that finding the area of a transformed parallelogram is the key.

- Consider the change-of-coordinates $x=2u$, $y=3v$.

- The lines $u=0,u=1,u=2$ and $v=0,v=1,v=2$ correspond to lines in the $xy$-plane. Draw these lines in the $xy$-plane (the line $v=1$ is done for you).

- The box in the $uv$-plane with $0\leq u\leq 1$ and $1\leq v\leq 2$ corresponds to a box in the $xy$-plane. Shade this box in the $xy$-plane and find its area.

- Compute the differentials $dx$ and $dy$. State them using the vector form (linear combination) $$\begin{pmatrix}dx\\dy\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} ?\\ ?\end{pmatrix}du+\begin{pmatrix}?\\?\end{pmatrix}dv$$ What do the two vectors $(a,0)$ and $(0,b)$ have to do with your picture?

- Draw the box given by $-1\leq u\leq 1$ and $-1\leq v\leq 1$ in both the $uv$-plane and $xy$-plane. Then state the area $A_{uv}$ of this box in the $uv$-plane, and state the area $A_{xy}$ of the corresponding rectangle in the $xy$-plane.

- Consider the circle $u^2+v^2=1$, whose area inside is $A_{uv}=\pi$. Guess the area $A_{xy}$ inside the corresponding ellipse in the $xy$-plane. Explain.

- The lines $u=0,u=1,u=2$ and $v=0,v=1,v=2$ correspond to lines in the $xy$-plane. Draw these lines in the $xy$-plane (the line $v=1$ is done for you).

- Consider now the change-of-coordinates $x=2u+v$, $y=u-2v$.

- The lines $u=0,u=1,u=2$ and $v=0,v=1,v=2$ correspond to lines in the $xy$ plane. Draw these lines in the $xy$-plane (the line $v=1$ is drawn for you). One option is to find the $xy$ coordinates of the $(u,v)$ points $(0,0)$, $(0,1)$, $(0,2)$, $(1,0)$, $(1,1)$, etc., and then just connect the dots to make a rotated grid.

- The box in the $uv$-plane with $0\leq u\leq 1$ and $1\leq v\leq 2$ should correspond to a parallelogram in the $xy$ plane. Shade this parallelogram in your picture above.

- Compute the differentials $dx$ and $dy$. State them using the vector form (linear combination) $$\begin{pmatrix}dx\\dy\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} ?\\ ?\end{pmatrix}du+\begin{pmatrix}?\\?\end{pmatrix}dv.$$ What do the two vectors above have to do with your picture?

- Show that the area of the parallelogram formed using these two vectors is 5. How would you describe the change in area between the graph in the $uv$-plane, and the graph in the $xy$-plane?

- The lines $u=0,u=1,u=2$ and $v=0,v=1,v=2$ correspond to lines in the $xy$ plane. Draw these lines in the $xy$-plane (the line $v=1$ is drawn for you). One option is to find the $xy$ coordinates of the $(u,v)$ points $(0,0)$, $(0,1)$, $(0,2)$, $(1,0)$, $(1,1)$, etc., and then just connect the dots to make a rotated grid.

The following code will help you check that your work on the second part is correct.

coordinates = {2 u + v, u - 2 v}

R = ParametricRegion[{coordinates, 0 <= u <= 1 && 1 <= v <= 2}, {u, v}];

Region[R, Axes -> True, AxesLabel -> {x, y}, AxesOrigin -> {0, 0}]

R = ParametricRegion[{coordinates, u == 0 || u == 1 || u == 2 || v == 0 || v == 1 || v == 2}, {{u, -1, 3}, {v, -1, 3}}];

Region[R, Axes -> True, AxesLabel -> {x, y}, AxesOrigin -> {0, 0}]

Task 34.2

Many vector fields are the derivative of a function. This function we call a potential for the vector field. Once we are comfortable finding potentials, we'll show that the work done by a vector field with a potential is the difference in the potential.

A potential for the vector field $\vec F$ is a function $f$ whose gradient equals $\vec F$, so $\vec \nabla f=\vec F$.

Let's practice finding gradients and potentials. You're welcome to watch this YouTube Video before starting, or just jump in and give it a try.

- Let $f(x,y) = x^2+3xy+2y^2$. Find $\vec \nabla f$. Then compute $D^2f(x,y)$ (you should get a square matrix). What are $f_{xy}$ and $f_{yx}$?

- Consider the vector field $\vec F(x,y)=(2x+y,x+4y)$. Find the derivative of $\vec F(x,y)$ (it should be a square matrix). Then find a function $f(x,y)$ whose gradient is $\vec F$ (i.e. $Df=\vec F$). What are $f_{xy}$ and $f_{yx}$?

- Consider the vector field $\vec F(x,y)=(2x+y,3x+4y)$. Find the derivative of $\vec F$. Why is there no function $f(x,y)$ so that $Df(x,y)=\vec F(x,y)$? [Hint: look at $f_{xy}$ and $f_{yx}$.]

Let $\vec F$ be a vector field that is everywhere continuously differentiable. Then $\vec F$ has a potential if and only if the derivative $D\vec F$ is a symmetric matrix. We say that a matrix is symmetric if interchanging the rows and columns results in the same matrix (so if you replace row 1 with column 1, and row 2 with column 2, etc., then you obtain the same matrix).

- For each of the following vector fields, start by computing the derivative. Then find a potential, or explain why none exists.

- $\vec F(x,y)=(2x-y, 3x+2y)$

- $\vec F(x,y)=(2x+4y, 4x+3y)$

- $\vec F(x,y)=(2x+4xy, 2x^2+y)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z)=(x+2y+3z,2x+3y+4z,2x+3y+4z)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z)=(x+2y+3z,2x+3y+4z,3x+4y+5z)$

- $\vec F(x,y,z)=(x+yz,xz+z,xy+y)$

The Mathematica code below starts by computing the derivative $D\vec F$, then uses DSolve to find a potential, and finishes by computing the gradient of the potential to see if it is the original vector field (verify you have the correct solution). If a potential exists, then the last line should match the first. You'll need to add a third variable (,z) in appropriate spots to use this code for a 3D vector field.

ClearAll[F, f, x, y]

F = {2 x + y, x + 4 y}

D[F, {{x, y}}] // MatrixForm

potential = DSolve[D[f[x, y], {{x, y}}] == F, f[x, y], {x, y}]

D[f[x, y] /. potential, {{x, y}}] // Flatten

Task 34.3

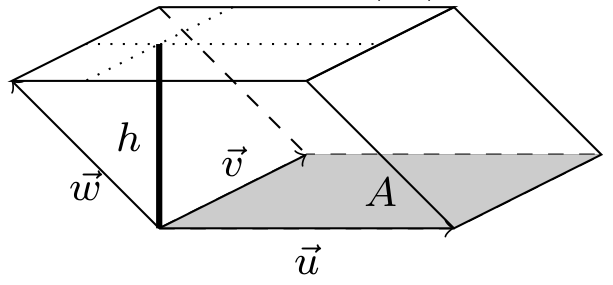

We already found the area of parallelogram in the $xy$-plane. To use new coordinate systems in 3D, we'll need to volume of a parallelepiped formed by the three vectors $\vec u$, $\vec v$, and $\vec w$, shown in the image below.

We get the volume by obtaining the area $A$ of one face, multiplied by the distance $h$ between the base and the plane containing the opposing face. This means we need to (1) compute the area of a parallelogram in 3D, and then (2) obtain a formula for the distance between the opposing faces. In this task, we'll see that the cross product and dot product provide us with precisely the tools we need to do both tasks.

- Let $\vec u = (a,b,c)$ and $\vec v = (d,e,f)$. Our goal is to find the area of a parallelogram whose edges are formed from these two vectors.

- Draw a picture that contains 2 vectors labeled $\vec u$ and $\vec v$. In that picture, include $\vec u_{\parallel \vec v}$ and $\vec u_{\perp\vec v}$. Explain why the area we seek is $A = |\vec u_{\perp\vec v}||\vec v|$. Then use the following Mathematica code to compute the area. The Assumptions command below is needed to help Mathematica do some simplifications .

$Assumptions = a \[Element] Reals && b \[Element] Reals && c \[Element] Reals && d \[Element] Reals && e \[Element] Reals && f \[Element] Reals; u = {a, b, c}; v = {d, e, f}; uPerpv = u - Projection[u, v]; Norm[uPerpv]*Norm[v] // Simplify - The magnitude of the cross product is $$|\vec u\times \vec v|= |(bf-ce, cd-af, ae-bd)| = \sqrt{(bf-ce)^2+ (cd-af)^2+ (ae-bd)^2}.$$ Show that the magnitude of the cross product and the area of the parallelogram (the value you obtained above) are the same. You can do this by hand, or with Mathematica. If you choose to use Mathematica, here is code for getting the magnitude of the cross product.

Norm[Cross[u, v]] // Simplify

- Use what you just learned to find the area of the parallelogram formed by the two vectors $(1,2,3)$ and $(-3,1,4)$.

- Draw a picture that contains 2 vectors labeled $\vec u$ and $\vec v$. In that picture, include $\vec u_{\parallel \vec v}$ and $\vec u_{\perp\vec v}$. Explain why the area we seek is $A = |\vec u_{\perp\vec v}||\vec v|$. Then use the following Mathematica code to compute the area. The Assumptions command below is needed to help Mathematica do some simplifications .

The cross product $\vec u\times\vec v$ of $\vec u$ and $\vec v$ is orthogonal to both $\vec u$ and $\vec v$. The magnitude of the cross product, so $|\vec u\times \vec v|$, is the area of the parallelogram formed by $\vec u$ and $\vec v$.

Now that we have a formula for the area of one face of a parallelepiped, we only need to find the distance between opposing faces to obtain the volume.

- Consider three vectors $\vec u$, $\vec v$, and $\vec w$ in $\mathbb{R}^3$. We will find the volume of the parallelepiped formed by these three vectors. Let the base of the parallelogram be the face formed by $\vec u$ and $\vec v$. The height $h$ is the distance between the plane that contains the base and the plane that contain the opposing side of the parallelepiped.

- Give a formula to compute the area of the base of the parallelogram. (What did the first part of this tasks help us learn)

- Give a vector $\vec n$ that is normal to the base.

- Use the projection formula, with the vectors $\vec w$ and $\vec n$ in an appropriate manner, to state the height $h$ of the parallelogram in terms of dot products.

- Use your work above to explain why the parallelepiped's volume is $$V=|(\vec u\times \vec v)\cdot \vec w|.$$

We call $(\vec u\times \vec v)\cdot \vec w$ the triple product of $\vec u$, $\vec v$, and $\vec w$. The volume of a parallelepiped formed by the three vectors is $V=|(\vec u\times \vec v)\cdot \vec w|.$

Task 34.4

Pick some problems related to the topics we are discussing from the Text Book Practice page.

|

Sun |

Mon |

Tue |

Wed |

Thu |

Fri |

Sat |