- I-Learn, Class Pictures, Learning Targets, Text Book Practice

- Prep Tasks: Unit 1 - Motion, Unit 2 - Derivatives, Unit 3 - Integration, Unit 4 - Vector Calculus

We still have some tasks from Day 26 to finish discussing in class.

Day 26 - Prep

Task 26.1

In this task we'll be focusing on locating the average, mean, center, etc., of something.

- Suppose a class takes a test and there are three scores of 70, five scores of 85, one score of 90, and two scores of 95. We will calculate the average class score, $\bar s$, four different ways to emphasize four ways of thinking about the averages. We are emphasizing the pattern of the calculations in this problem, rather than the final answer, so it is important to write out each calculation completely, without doing any simplifying, before calculating the number $\bar s$.

- Compute the average by adding 11 numbers together and dividing by the number of scores ($\bar s=\frac{\sum \text{values}}{\text{number of values}}$). Write down the whole computation before doing any arithmetic.

- Compute the numerator of the fraction in the previous part by multiplying each score by how many times it occurs, rather than adding it in the sum that many times ($\bar s=\frac{\sum (\text{value}\cdot\text{weight})}{\sum \text{weight}}$). Again, write down the calculation for $\bar s$ before doing any arithmetic.

- Compute $\bar s$ by splitting up the fraction in the previous part into the sum of four numbers ($\bar s=\sum (\text{value}\cdot\text{(\% of stuff)})$). This is called a weighted average because we are multiplying each score value by a weight.

- Another way of thinking about the average $\bar s$ is that $\bar s$ is the number so that if all 11 scores were the same value $\bar s$, you'd have the same sum of scores ($\text{ (number of values) }\bar s = \sum \text{values}$ or $(\sum \text{weight})\bar s = \sum (\text{value}\cdot\text{weight})$). Write this way of thinking about these computations by taking the formulas for $\bar s$ in the first two parts and multiplying both sides by the denominator.

We now generalize the above ways of thinking about averages from a discrete situation to a continuous situation. We did this in first-semester calculus when we computed the average value of $f$ using integrals.

- Suppose the price of a stock is \$10 for two days. Then the price of the stock jumps to \$20 for three days. Our goal is to determine the average price of the stock over the total 5 day period.

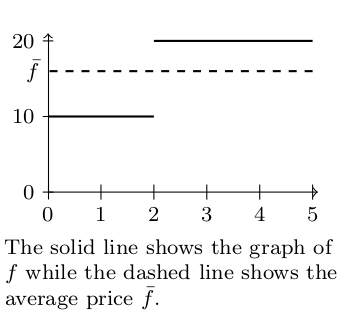

- Why is the average stock price not \$15? Use any of the methods from the previous problem to show that the average price is $\bar f=\$16$.

- The function $f(t) = \begin{cases}10 &0\leq t<2\\20&2\leq t\leq 5\end{cases}$ models the price of the stock for the 5-day period. The graph below shows both the function $f$ and the average stock price $\bar f$. Show that the area under $f$ for $0\leq t\leq 5$ is 80. Then show that the area under $\bar f$ for $0\leq t\leq 5$ is also 80.

- The average value of a function over an interval $ [a,b] $ is a constant value $\bar f$ so that the areas under both $f$ and $\bar f$ are equal, which means $\ds\int_a^b \bar f dx = \int_a^b f dx.$ Solve for $\bar f$ to show that $$\bar f = \dfrac{\ds\int_a^b f dx}{\ds\int_a^b dx}.$$

Let's examine one last averaging question, this time as it relates to a rover. If we know the mass and center-of-mass of each part of the rover, we can use weighted averages to combine these values and obtain the center-of-mass of the the entire rover.

- Consider a simplified rover with a bottom and a top.

- The bottom part of the rover has a volume of $V_1$ m$^3$, a constant density (mass per volume) of $\delta_1$ g/m$^3$, and a center-of-mass located at $(\bar x_1,\bar y_1,\bar z_1)$.

- The top part of the rover has a volume of $V_2$ m$^3$, a constant density (mass per volume) of $\delta_2$ g/m$^3$, and a center-of-mass located at $(\bar x_2,\bar y_2,\bar z_2)$.

- Give the masses $m_1$ and $m_2$ of the bottom and top of the rover. Explain.

- What proportion of the total mass comes from the bottom of the rover?

- Explain why the center-of-mass of the entire rover is $$\left(\frac{\bar x_1(m_1)+\bar x_2(m_2)}{m_1+m_2},\frac{\bar y_1(m_1)+\bar y_2(m_2)}{m_1+m_2}, \frac{\bar z_1(m_1)+\bar z_2(m_2)}{m_1+m_2}\right) .$$

- The rover picks up an additional object. The object's mass is $m_3$ with center-of-mass $(\bar x_3, \bar y_3, \bar z_3)$. Modify the formula above to give the center-of-mass of the rover, together with the new object. Try writing the formula using summation notation.

Task 26.2

To find the mass of a thin metal plate occupying a region $R$ in the $xy$-plane, we add up the little masses (differentials) $dm = \delta(x,y)dA$, where $\delta$ is the density (mass per area), to obtain the mass as $$m=\iint_R\delta(x,y)dA = \iint_R\delta(x,y) dxdy= \iint_R\delta(x,y) dydx. $$ Note that if $\delta(x,y)=1$, then this reduces to the formula for the area of $R$. This task has you practice setting up area and mass integrals.

For each region $R$ below, draw the region. Then set up an iterated double integral which would give the area of the region. Then use the density provided to set up an iterated double integral that would give the mass of a metal plate occupying this region with the given density. You do not need to compute each integral, rather just set it up.

- The region $R$ is above the line $x+y=1$ and inside the circle $x^2+y^2=1$. The density is $\delta(x,y)=x$.

- The region $R$ is below the line $y=8$, above the curve $y=x^2$, and to the right of the $y$-axis. The density is $\delta(x,y)=xy^2$.

- The region $R$ is bounded by $2x+y=3$, $y=x$, and $x=0$. The density is $\delta(x,y)=7$.

Task 26.3

Consider the change-of-coordinates $x=r\cos \theta$ and $y=r\sin\theta$.

- The lines $r=1,r=2,r=3$ and $\theta=0,\theta=\frac{\pi}{6},\theta=\frac{\pi}{3}$ correspond to circles and lines in the $xy$ plane. Draw these circles and lines in the $xy$-plane.

- The box in the $r\theta$ plane with $2\leq r\leq 3$ and $\frac{\pi}{6}\leq \theta\leq \frac{\pi}{3}$ corresponds to a region in the $xy$ plane. Shade this region in the $xy$ plane.

- Let $(r,\theta)$ be an arbitrary point. Our goal is to develop a formula for the area of the region $R$ in the $xy$ plane where the radius ranges from $r$ to $r+dr$ and the angle ranges from $\theta$ to $\theta +d\theta$, shown in the diagram below.

- Add the labels $r$, $\theta$, $dr$, $d\theta$, $r+dr$, and $\theta +d\theta$ to appropriate places in your diagram.

- The shaded region is approximately a rectangle. Letting the width of the rectangle be $dr$, explain why the height of the rectangle can be approximated by $rd\theta$. This means that a little area is give by $dA=rdrd\theta$.

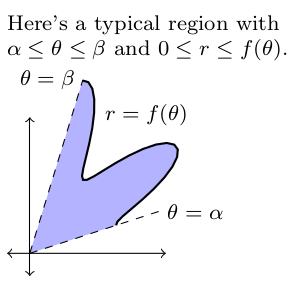

- Consider the region $R$ in the $xy$ plane bounded by $\alpha\leq \theta\leq \beta$ and $0\leq r\leq f(\theta)$ (shown below). The area of such a region $R$ in the $xy$ plane is the double integral $A=\int\int_R dA$. Explain why the area of the region in the $xy$ plane, when using polar coordinates, is $$A=\int_\alpha^\beta\int_0^{f(\theta)} rdrd\theta.$$

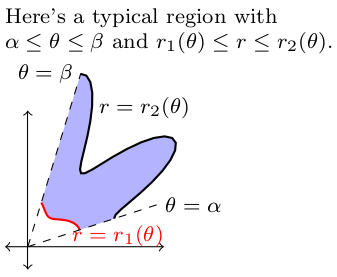

- Now consider the region $R$ bounded by $\alpha\leq \theta\leq \beta$ and $r_1(\theta)\leq r\leq r_2(\theta)$. Set up a double integral that would give the area of this region $R$.

Task 26.4

Pick some problems related to the topics we are discussing from the Text Book Practice page.

Day 27 - Prep

Task 27.1

We can think of any object (such as a rover) as consisting of many little parts. Each little part contributes a little mass $dm$ and a center-of-mass. We can predict these quantities prior to building the rover, before we can weigh anything. We just need the length $ds$, area $dA$, or volume $dV$ of a small part, together with the material's density $\delta$ (mass per length, area, or volume, as appropriate).

- For thin wires, we get little masses $dm$ by multiplying little lengths $ds$ by a density $\delta$ with units of mass per length.

- For thin plates, we get little masses $dm$ by multiplying little areas $dA$ by a density $\delta$ with units of mass per area.

- For solid objects, we get little masses $dm$ by multiplying little volumes $dV$ by a density $\delta$ with units of mass per volume.

In all three cases, we can obtain the total mass $m$ by adding up the little masses with an integral. The difference between the three cases will be whether we use a single, double, or triple integral. Often the density $\delta$ will be constant throughout an entire object. However, composite materials exist where density $\delta (x,y,z)$ can vary throughout an object. We can then compute the center-of-mass using the average value formula.

Consider a thin rod (like a drive shaft or thinner) that lies along the $z$-axis for $a\leq z\leq b$.

- Suppose first that the rod is made out of a single material whose density is given by the constant $\delta$ g/m (mass per length).

- A small part of the rod has length $dz$. Compute $\int_a^b dz$, and explain what physical quantity this integral computes.

- A small bit of the rod has mass $dm = \delta dz$. Compute the total mass by computing $\int_a^b \delta dz$. Remember that $\delta$ is a constant.

- Guess the location of the average $z$-value of the rod (the center-of-mass).

- To validate your guess, compute and simplify the average value integral formula $$\bar z = \frac{\ds\int_a^b z dm}{\ds\int_a^b dm} = \frac{\ds\int_a^b z \delta dz}{\ds\int_a^b \delta dz}.$$

- Now suppose the rod is more like an antenna and the rod gets thinner as we move up the rod. This means the density $\delta(z)$ is now a function of $z$. Let's use, for simplicity, the linear density function $\delta(z)=b-z$.

- What is the density of the rod at $a$? What is the density of the rod at $b$? Construct a rough sketch of a rod that could have this type of density function.

- A small bit of the rod has mass $dm = \delta(z) dz$. Compute the total mass by computing $\int_a^b \delta(z) dz = \int_a^b (b-z)dz$.

- Is the location of $\bar z$ closer to $z=a$ or $z=b$? Explain.

- Find the $z$-coordinate of the center-of-mass by computing $$\bar z = \frac{\ds\int_a^b z dm}{\ds\int_a^b dm} = \frac{\ds\int_a^b z \delta dz}{\ds\int_a^b \delta dz}.$$ Feel free to use software. Verify that $\bar z = \frac{2a+b}{3}$.

Above we performed computations for a rod that lies on an axis. This works great for a drive shaft, or antenna, or any part of the rover that consists of a straight thin rod. But we can repeate these computations for a portion of the rover that is a thin flat plate, such as a solar panel, an armored plate, or any object which is best described by thinking of the area.

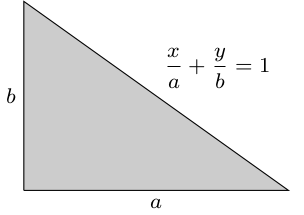

- Consider the triangular region $R$ in the first quadrant that lies under the line $\ds\frac{x}{a}+\frac{y}{b}=1$. If you would rather work with numbers instead of variables, feel free to let $a=5$ and $b=7$ in this problem.

- Compute the double integral $\ds\int_0^a\int_0^{b(1-\frac{x}{a})} dy dx$. What physical quantity of the region $R$ does this integral give?

- The density of the metal plate is $\delta$ g/m$^2$. Set up a double integral formula to compute the mass of the region using this density.

- The center-of-mass in the $x$-direction is given by the formula $$\bar x = \frac{\ds\iint_R xdm}{\ds\iint_R dm}= \frac{\ds\int_0^a\int_0^{b(1-\frac{x}{a})} x \delta dy dx}{\ds\int_0^a\int_0^{b(1-\frac{x}{a})} \delta dy dx}.$$ Assuming $\delta$ is constant, compute this integral and show that $\bar x = \frac{a}{3}$. Feel free to use software.

- Set up an integral formula, like the one above, to compute $\bar y$. Show the integral formula you used, and then state the value $\bar y$ obtained.

Task 27.2

- Consider the region $R$ in the $xy$-plane that is below the line $y=x+2$, above the line $y=2$, and left of the line $x=5$. We can describe this region by saying for each $x$ with $0\leq x\leq 5$, we want $y$ to satisfy $2\leq y\leq x+2$. In set builder notation, we write $$R=\{(x,y)\in \mathbb{R}^2\mid 0\leq x\leq 5, 2\leq y\leq x+2\}.$$ We use the symbols $\{$ and $\}$ to enclose sets and the symbol $\mid$ for "such that". We read the above line as "$R$ equals the set of $(x,y)$ in the plane such that zero is less than $x$ which is less than 5, and 2 is less than $y$ which is less than $x+2$." The iterated double integral $\int_0^5\int_2^{x+2} dy dx$ gives the area of this region.

- Draw this region.

- Describe the region $R$ by saying for each $y$ with $c\leq y\leq d$, we want $x$ to satisfy $a(y)\leq x\leq b(y)$. In other words, find constants $c$ and $d$, and functions $a(y)$ and $b(y)$, so that for each $y$ between $c$ and $d$, the $x$ values must be between the functions $a(y)$ and $b(y)$. Write your answer using the set builder notation $$R=\{(x,y)\ | \ c\leq y\leq d, a(y)\leq x\leq b(y)\}.$$

- Finish setting up the iterated double integral $\int_?^?\int_?^? dx dy$.

- Compute both $\int_0^5\int_2^{x+2} dy dx$ and $\int_?^?\int_?^? dx dy$ (the integral you just set up), and verify that they give the same value.

- Consider the iterated integral $\ds \int_0^3\int_x^3 e^{y^2}dydx$. We could think of the function $e^{y^2}$ as a density, but notice that this function is independent of the region described by the bounds of the integral.

- Write the bounds as two inequalities ($0\leq x\leq 3$ and $?\leq y\leq ?$). Then draw and shade the region $R$ described by these two inequalities.

- Swap the order of integration from $dydx$ to $dxdy$. This forces you to describe the region using two inequalities of the form $c\leq y\leq d$ and $a(y)\leq x\leq b(y)$, obtaining the iterated double integral $\ds \int_?^?\int_?^? e^{y^2}dxdy$.

- Use your new bounds to compute the integral by hand.

- Why is the original integral $\ds \int_0^3\int_x^3 e^{y^2}dydx$ impossible to compute without first swapping the order of integration [Hint: Try computing the inner integral $\int_x^3 e^{y^2}dy$ -- why can't you? What does Mathematica give if you try to compute this inner integral?]

Task 27.3

I won't add another task. Work on the previous tasks, and come ready to discuss them.

Task 27.4

Pick some problems related to the topics we are discussing from the Text Book Practice page.

Day 27 - In class

Brain Gains (Rapid Recall, Jivin' Generation)

- A metal plate covers the region in the first quadrant that lies below the parabola $y=9-x^2$. The density (mass per area) at points in the plate is given by the function $\delta = xy$. Set up an iterated double integral that would give the mass of this metal plate.

Solution

The solution is $\ds\iint_Rdm =\iint_R\delta dydx = \int_0^3\int_0^{9-x^2}(xy)dydx$.

Here's some easy to modify Mathematica code that will compute the integral for you, as well as draw the region to help you know that what you gave for the bounds is correct.

OuterBounds = {x, 0, 3};

InnerBounds = {y, 0, 9 - x^2};

Integrand = x y;

Integrate[Integrand, OuterBounds, InnerBounds]

CoordinateSystem = {x, y};

ParametricPlot[CoordinateSystem, OuterBounds, InnerBounds, Mesh -> {10, 0}]

ParametricPlot[Evaluate[CoordinateSystem, OuterBounds, InnerBounds], Mesh -> {10, 0}]

- Set up iterated integral formulas that would give the center of mass $\bar x$ and $\bar y$ for the region in the previous part.

Solution

We have $\ds\bar x = \frac{\iint_Rxdm}{\iint_Rdm} =\frac{\iint_Rxdydx}{\iint_Rdydx} = \frac{\int_0^3\int_0^{9-x^2}x(xy)dydx}{\int_0^3\int_0^{9-x^2}xydydx}$.

The only difference for $\bar y$ is we change the $x$ to a $y$, so that we are finding the average $y$ value, instead of the average $x$-value. This gives $\ds\bar y = \frac{\iint_Rydm}{\iint_Rdm} =\frac{\iint_Rydydx}{\iint_Rdydx} = \frac{\int_0^3\int_0^{9-x^2}y(xy)dydx}{\int_0^3\int_0^{9-x^2}xydydx}$.

OuterBounds = {x, 0, 3};

InnerBounds = {y, 0, 9 - x^2};

density = x y;

Integrate[x*density, OuterBounds, InnerBounds]/Integrate[density, OuterBounds, InnerBounds]

Integrate[y*density, OuterBounds, InnerBounds]/Integrate[density, OuterBounds, InnerBounds]

CoordinateSystem = {x, y};

ParametricPlot[CoordinateSystem, OuterBounds, InnerBounds, Mesh -> {10, 0}]

ParametricPlot[Evaluate[CoordinateSystem, OuterBounds, InnerBounds], Mesh -> {10, 0}]

- What is the difference between the three double integrals $\iint_RdA$, $\iint_Rdydx$, and $\iint_Rdxdy$?

Solution

The three integral notations all add up area. The first notation assumes you have cut the region up into tiny rectangles where both the width and height have been reduced. The second slices a region up into vertical slabs with a tiny width $dx$. The later assumes the slabs are horizontal, with a tiny height $dy$. They all compute the same number, just in a different way. Fubini's theorem provides precise details under which these three integrals are guaranteed to be equal.

We can use the Mesh command in Mathematica to quickly visualize this.

xBounds = {x, 0, 3};

yBounds = {y, 0, 9 - x^2};

CoordinateSystem = {x, y};

ParametricPlot[Evaluate[CoordinateSystem, xBounds, yBounds], Mesh -> {20, 20}]

ParametricPlot[Evaluate[CoordinateSystem, xBounds, yBounds], Mesh -> {20, 0}]

ParametricPlot[Evaluate[CoordinateSystem, xBounds, yBounds], Mesh -> {0, 20}]

- Set up an iterated integral, using polar coordinates, that would give the area in the second quadrant inside a circle or radius 5 that is centered at the origin.

Solution

The area is $\ds\iint_RdA =\iint_Rr drd\theta = \int_{\pi/2}^{\pi}\int_0^{5}rdrd\theta$.

Here's some code that will plot any polar region. The key is to use the change-of-coordinates $x = r\cos\theta$ and $y=r\sin\theta$. This code can be adapted to work with any change of coordinates, which we'll focus on in a couple weeks.

OuterBounds = {theta, Pi/2, Pi};

InnerBounds = {r, 0, 5};

Integrand = r;

Integrate[Integrand, OuterBounds, InnerBounds]

CoordinateSystem = {r Cos[theta], r Sin[theta]};

ParametricPlot[CoordinateSystem, OuterBounds, InnerBounds, Mesh -> {10, 0}]

ParametricPlot[Evaluate[CoordinateSystem, OuterBounds, InnerBounds], Mesh -> {10, 0}]

- Set up iterated integral formulas, using polar coordinates, that would give the centroid (center of mass, assuming constant density) of the region above.

Solution

The centroid $(\bar x, \bar y)$ is the point that gives the average $(x,y)$ coordinates of the points in the region. It's the geometric center, and variable densities are ignored. These are just average $x$ and $y$ values, so we use the average value formula $\bar f = \frac{\iint_R f dA}{\iint_R dA}$, with $f$ equal to $x$ and $y$ respectively, to obtain

- $\ds\bar x = \frac{\iint_RxdA}{\iint_RdA} =\frac{\iint_R(r\cos\theta)rdrd\theta}{\iint_Rrdrd\theta} = \frac{\int_{\pi/2}^{\pi}\int_0^{5}rdrd\theta}{\int_{\pi/2}^{\pi}\int_0^{5}(r\cos\theta)rdrd\theta}$ and

- $\ds\bar y = \frac{\iint_RxdA}{\iint_RdA} =\frac{\iint_R(r\sin\theta)rdrd\theta}{\iint_Rrdrd\theta} = \frac{\int_{\pi/2}^{\pi}\int_0^{5}rdrd\theta}{\int_{\pi/2}^{\pi}\int_0^{5}(r\sin\theta)rdrd\theta}$.

With Mathematica, we can quickly compute these.

OuterBounds = {theta, Pi/2, Pi};

InnerBounds = {r, 0, 5};

Integrate[(r Cos[theta]) r, OuterBounds, InnerBounds]/Integrate[r, OuterBounds, InnerBounds]

Integrate[(r Sin[theta]) r, OuterBounds, InnerBounds]/Integrate[r, OuterBounds, InnerBounds]

CoordinateSystem = {r Cos[theta], r Sin[theta]};

ParametricPlot[CoordinateSystem, OuterBounds, InnerBounds, Mesh -> {10, 0}]

ParametricPlot[Evaluate[CoordinateSystem, OuterBounds, InnerBounds], Mesh -> {10, 0}]

Group Problems

Pick up where you left off yesterday (or just restart), and work though as many as you can.

- A metal plate lies in the rectangle $ [-2,6]\times [1,5] $ (so $-2\leq x\leq 6$ and $1\leq y \leq 5$ ).

- What is the center-of-mass $(\bar x,\bar y)$ of the metal plate? (Where is the geometric center?)

- Compute the integral formula $\bar x = \ds\frac{\int_{-2}^{6}\int_1^5 x dydx}{\int_{-2}^{6}\int_1^5 1 dydx}.$ [Check: 64/32=2.]

- Compute the integral formula $\bar y = \ds\frac{\int_{-2}^{6}\int_1^5 y dydx}{\int_{-2}^{6}\int_1^5 1 dydx}.$ [Check: 96/32=3.]

- Compute the integral formula $\bar x = \ds\frac{\int_1^5 \int_{-2}^{6}x dxdy}{\int_1^5 \int_{-2}^{6}1 dxdy}$, to verify that swapping the order of integration still yields $\bar x = 2$.

- Draw the region described by the bounds of each integral.

- $\ds\int_{0}^{2}\int_{2x}^{4}dydx$

- $\ds\int_{0}^{4}\int_{0}^{y/2}dxdy$

- $\ds\int_{0}^{3\pi/2}\int_{0}^{2+2\cos\theta}rdrd\theta$

- $\ds\int_{-3}^{3}\int_{0}^{9-x^2}\int_{0}^{5}dzdydx$

- $\ds\int_{0}^{1}\int_{0}^{1-z}\int_{0}^{\sqrt{1-x^2}}dydxdz$

Here's 2 options for plotting the first region in Mathematica.

ContourPlot[{x == 0, x == 2, y == 2 x, y == 4}, {x, -1, 3}, {y, -1, 5}]

RegionPlot[ x >= 0 && x <= 2 && y >= 2 x && y <= 4, {x, -1, 3}, {y, -1, 5}]

Here's two options for the first 3D plot in Mathematica.

ContourPlot3D[{x == -3, x == 3, y == 0, y == 9 - x^2, z == 0, z == 5}, {x, -4, 4}, {y, -1, 10}, {z, -1, 6}]

RegionPlot3D[x >= -3 && x <= 3 && y >= 0 && y <= 9 - x^2 && z >= 0 && z <= 5, {x, -4, 4}, {y, -1, 10}, {z, -1, 6}]

- Set up an integral formula to compute each of the following:

- The mass of a disc that lies inside the circle $x^2+y^2=9$ and has density function given by $\delta = x+10$

- The $x$-coordinate of the center of mass (so $\bar x$) of the disc above.

- The $z$-coordinate of the center-of-mass (so $\bar z$) of the solid object in the first octant (all variables positive) that lies under the plane $2x+3y+6z=6$.

- The $y$-coordinate of the center-of-mass (so $\bar y$) of the same object.

Day 28 - Prep

Task 28.1

We have seen how to compute the center of mass of a rod (a 1 dimensional object) and triangle (a 2 dimensional object). This task will do so with a circular region (2 dimensional object) and 3D solid.

- Consider the semicircular disc $R$ that lies above the $x$-axis and below the circle of radius $a$. If you would rather work with numbers instead of variables, feel free to let $a=5$ for this problem.

- We know the area of $R$ is $\frac{1}{2}\pi a^2$. Set up a double integral using polar coordinates to compute this area. Then compute the integral by hand and simplify your work to obtain the correct area.

- Let's assume the density for this problem is $\delta = 1$, so that $dm=dA$. When the density is constant, we use the word "centroid" instead of "center-of-mass" to talk about the geometric center of an object. The centroid in the $x$-direction is given by the formula $$\bar x = \frac{\ds\iint_R xdA}{\ds\iint_R dA}= \frac{\ds\int_0^\pi\int_0^{a} \overbrace{(r\cos\theta)}^{x} \overbrace{r dr d\theta}^{dA}}{\ds\int_0^\pi\int_0^{a} \underbrace{r dr d\theta}_{dA}}.$$ Compute the integrals above, by hand, to show that $\bar x=0$.

- Set up an integral formula, like the one above, to compute $\bar y$. Show the integral formula you used, and then compute it (feel free to use software) to obtain $\bar y$. You can check your answer is correct by referring to a list of centroid of regions (such as this Wikipedia list).

- The triple integral $\ds\int_{0}^{5}\int_0^7\int_{0}^{10-2x}dzdydx$ gives the volume of a solid domain $D$ in space.

- Draw the solid domain $D$ described by the bounds of the integral above. This is the solid satisfying the inequalities $0\leq x\leq 5$, $0\leq y\leq 7$, and $0\leq z\leq 10-2x$.

- Let $\delta =1$ so that $dm=\delta dV = 1dV$. The centroid of $D$ has three coordinates $(\bar x, \bar y, \bar z)$. The $x$-coordinate is given by the integral formula $$\bar x = \frac{\ds\iiint_R xdV}{\ds\iiint_R dV}= \frac{\ds\int_{0}^{5}\int_0^7\int_{0}^{10-2x}(x)dzdydx}{\ds\int_{0}^{5}\int_0^7\int_{0}^{10-2x}1dzdydx}.$$ Compute this triple integral and simplify to show that $\bar x = \frac{5}{3}$.

- Modify the above formula to obtain integral formulas for both $\bar y$ and $\bar z$. Then state the values of $\bar y$ and $\bar z$, either by using facts we've already proven or by computing the integrals directly (use software).

Task 28.2

For each region $R$ below, draw the region in the $xy$-plane. Set up an iterated integral in polar coordinates ($x=r\cos\theta$, $y=r\sin\theta$) that gives the area of the region and then use the given density to set up an iterated double integral that gives the mass of a metal plate that occupies the region and has the given variable density. Use software to compute each integral.

For example, consider the region that is inside the circle $x^2+y^2=9$, along with the density $\delta(x,y)=y^2$. We can describe the region using the polar inequalities $0\leq \theta \leq 2\pi$ and $0\leq r\leq 3$, which gives us the bounds needed for our integral.

- The area is $\ds A=\iint_R \delta dA = \int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^3\underbrace{rdrd\theta}_{dA} = 9\pi.$

- The mass is $\ds m=\iint_R \delta dA = \int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^3\underbrace{(r\sin\theta)^2}_{\delta=y^2}\underbrace{rdrd\theta}_{dA} = \frac{81\pi}{4}.$

The Mathematica code below was used to compute the integrals above (along with a graphical check that the region is the correct region - the last line is there for backwards compatibility, and can be ignored if you have Mathematica 13.0 or greater).

OuterBounds = {theta, 0, 2 Pi};

InnerBounds = {r, 0, 3};

Integrate[r, OuterBounds, InnerBounds]

Integrate[(r Sin[theta])^2 r, OuterBounds, InnerBounds]

CoordinateSystem = {r Cos[theta], r Sin[theta]};

ParametricPlot[CoordinateSystem, OuterBounds, InnerBounds, Mesh -> {10, 0}]

ParametricPlot[Evaluate[CoordinateSystem, OuterBounds, InnerBounds], Mesh -> {10, 0}]

- The region $R$ is the quarter disc in the first quadrant that lies inside the circle $x^2+y^2=25$. The density is $\delta(x,y)=x$.

- The region $R$ is bounded above by $y=\sqrt{9-x^2}$, bounded below by $y=x$, and bounded on the left by the $y$-axis. The density is $\delta(x,y)=xy^2$.

- The region $R$ is the inside of the cardioid $r=3+3\cos\theta$. The density is $\delta(x,y)=7$.

- The region $R$ is the triangular region below $y=\sqrt 3 x$, above the $x$-axis, and to the left of $x=1$. The density is $\delta(x,y)=7$.

Task 28.3

This task provides you with a couple integrals that cannot be done, without first making some change. The first requires a change of order of integration. The second requires a complete change of coordinates.

- Compute by hand the iterated integral $$\ds \int_0^{2\sqrt{\pi}}\int_{y/2}^{\sqrt{\pi}} \sin(x^2)dxdy.$$ (Hint, you will need to swap the order of integration first.)

- The double integral $\ds\int_0^{\sqrt{2}}\int_{y}^{\sqrt{4-y^2}} e^{x^2+y^2}dxdy$ computes the mass of a region in the plane with density $\delta = e^{x^2+y^2}$ that is bounded by the curves $y=0$, $y=\sqrt{2}$, $x=y$, and $x=\sqrt{4-y^2}$.

- Draw the region described by these bounds. (Did you get a sector of a circle, something like a 1/8th of a pizza?)

- Give bounds of the form $?\leq \theta\leq ?$ and $?\leq r\leq ?$ that describe the region using polar coordinates. (The new bounds are all constants.)

- Convert the Cartesian integral to an integral in polar coordinates (don't forget the $r$ that appears as $dxdy = dA = rdrd\theta$).

- Compute the integral by hand. Show your steps.

Task 28.4

Pick some problems related to the topics we are discussing from the Text Book Practice page.

|

Sun |

Mon |

Tue |

Wed |

Thu |

Fri |

Sat |