- I-Learn, Class Pictures, Learning Targets, Text Book Practice

- Prep Tasks: Unit 1 - Motion, Unit 2 - Derivatives, Unit 3 - Integration, Unit 4 - Vector Calculus

We still have Task 13.3 to discuss in class.

Day 13 - Prep

Task 13.1

For the function $f(x,y) = 9-x^2-y^2$, we can compute the differential $df = -2xdx-2ydy$, the partial derivatives $f_x = -2x$ and $f_y=-2y$, along with the gradient $\vec \nabla f(x,y) = (-2x,-2y)$. Notice that the gradient is a vector field, so at the point $(x,y)$ we can draw the vector $(-2x,-2y)$.

- Construct a plot of the vector field $\vec \nabla f(x,y) = (-2x,-2y)$.

- Add to your vector field plot a contour plot of $f(x,y) = 9-x^2-y^2$ (we constructed a contour plot for the function in a previous Task).

- What relationships do you see between the vectors from the gradient plot, and the level curves from your contour plot.

For the function $f(x,y) = x^2-y$, we can compute the differential $df = 2xdx-1dy$, the partial derivatives $f_x = 2x$ and $f_y=-1$, along with the gradient $\vec \nabla f(x,y) = (2x,-1)$. Again, notice that the gradient is a vector field, so at the point $(x,y)$ we can draw the vector $(2x,-1)$.

- Construct a plot of the vector field $\vec \nabla f(x,y) = (2x,-1)$.

- Add to your vector field plot a contour plot of $f(x,y) = x^2-y$ (we constructed a contour plot for the function in a previous Task).

- What relationships do you see between the vectors from the gradient plot, and the level curves from your contour plot.

You can use the Mathematica file ContourSurfaceGradient.nb to check your work.

Task 13.2

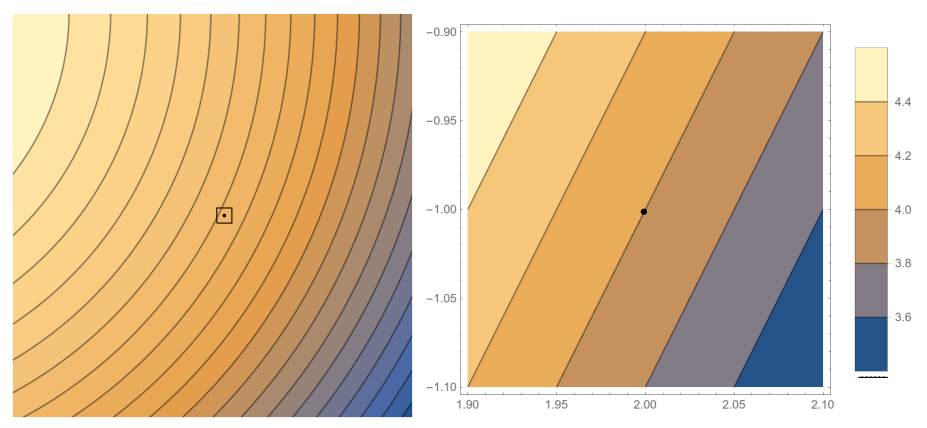

Suppose the Mars rover Curiosity is currently on a hill, and its position is at the center of the map on the left below. Zooming in on the rover's position yields the map on the right below (the color legend applies to the graph on the right).

The contours in the graph to the right each represent a change in height of 0.2 units. The bounds for the graph are $1.9\leq x\leq 2.1$ and $-1.1\leq y\leq -0.9$. For simplicity of computations, let's assume the $x$, $y$ and $z$ axes use the same units. The rover is currently located at the point $(2,-1)$, shown as a dot.

The rover can head in many directions. In this problem we'll estimate the slope in several directions. For example, if the rover follows the vector $(0,1)$, heads north, then it has to move a distance (run) of $\Delta y = 0.1$ units to hit the next contour, resulting in a change in height of $\Delta z = +0.2$ units. This means the slope in the $(0,1)$ direction is $$\ds\frac{\text{rise}}{\text{run}} = \frac{\Delta z}{\text{distance moved in $xy$ plane}} = \frac{+0.2}{0.1} = 2.$$

- Estimate the slope if the rover heads east, following $(1,0)$.

- If the rover heads south, following $(0,-1)$, estimate the slope.

- If the rover follows the direction $(1,1)$ (so northeast), what distance must the rover travel to hit the next contour? Use this to estimate the slope in the $(1,1)$ direction.

- Estimate the slope in the $(1,2)$ direction.

Rather than starting with a contour plot and using it to visually estimate slopes, let's start with a function of the form $z=f(x,y)$ and use it to compute slopes. Suppose the elevation $z$ of terrain near the rover is given by the formula $z=f(x,y) = x^2+3xy$, and the rover is currently at $P=(2,-1)$.

- Compute the differential $dz$ and write it in the form $dz = (?)dx+(?)dy$. Then evaluate $dz$ at the rover's location $P=(2,-1)$. [Check: Did you get $dz = (1)dx+(6)dy$?]

- If the rover follows the direction $(dx,dy)$, explain why the slope is $\frac{dz}{\sqrt{(dx)^2+(dy)^2}}$.

- Estimate the slope if the rover heads east, following $(dx,dy)=(1,0)$. Then estimate the slope if the rover heads north, following $(dx,dy)=(0,1)$. What do these values have to do with the partial derivatives of $f$?

- Estimate the slope in the $(1,1)$ direction and then the $(1,2)$ direction.

Task 13.3

The volume of a right circular cylinder is $V(r,h)= \pi r^2 h$.

- If we think of $h$ as a constant, so that $V(r)$ is only a function of $r$, then compute $\frac{dV}{dr}$.

- If instead we think of $r$ as a constant, so that $V(h)$ is only a function of $h$, then compute $\frac{dV}{dh}$.

- Compute the differential of $V(r,h)$, and then state the gradient $\vec \nabla V(r,h)$ along with the partial derivatives $\frac{\partial V}{\partial r}$ and $\frac{\partial V}{\partial h}$.

- If we know $r=3$ and $h=4$, and we know that $r$ could increase by $dr=0.1$ and $h$ could increase by about $dh=0.2$, then use differentials to estimate how much $V$ will increase.

Notice that we were able to compute the partial derivatives above, without ever needing to compute the differential first. We obtain $\frac{\partial V}{\partial r}$ by imagining that every variable other than $r$ was a constant, and then computing the regular derivative.

- The volume of a box is given by $f(x,y,z)=xyz$. Without computing the differential, compute $\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}$, $\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}$, and $\frac{\partial f}{\partial z}$.

- Now compute the differential $df$ (use implicit differentiation if needed) and verify that the partial derivatives you computed before actually show up in the differential $df$.

- If the current measurements are $x=2$, $y=3$, and $z=5$, and we know that expected tolerances are $dx=.01$, $dy=.02$, and $dz=.03$, then estimate the change in volume.

Task 13.4

The last problem for prep each day will point to relevant problems from OpenStax. Spend 30 minutes working on problems from the sections below.

- section 4.3, exercises 118-131

Day 15 - Prep

Every time we compute a differential $df = f_xdx+ f_ydy$, we're following a pattern that shows up so often that it's given a name (linear combination). At some point you may take a linear algebra course where you'll focus quite a bit on linear combinations, and quickly adopt matrices to help speed up the process of writing linear combinations.

Given $n$ vectors $\vec v_1, \vec v_2,\cdots,\vec v_n$ and $n$ scalars $c_1, c_2, \cdots, c_n$ the linear combination of these vectors using these scalars is the sum $$\sum_{i=1}^n c_1 \vec v_i = c_1\vec v_1+c_2\vec v_2+\cdots+c_n\vec v_n.$$ Matrix notation and products were invented to organize linear combinations into a visually appealing compact form. We place each vector in the column of a matrix, and then place the corresponding scalars into a single column vector after the matrix. The linear combination above, in matrix form, becomes the matrix product $$c_1\vec v_1+c_2\vec v_2+\cdots+c_n\vec v_n = \begin{bmatrix} \begin{pmatrix}\\\vec v_1\\ \ \end{pmatrix} &\begin{pmatrix}\\\vec v_2\\ \ \end{pmatrix} &\cdots &\begin{pmatrix}\\\vec v_n\\ \ \end{pmatrix} \end{bmatrix} \begin{pmatrix}c_1\\c_2\\\vdots\\c_n\end{pmatrix}.$$

The derivative (or total derivative) of a function is a matrix whose columns are the partial derivatives of the function. The partial derivatives we insert into the columns of the matrix in the same order in which the variables are listed for the function. Some examples follow.

- For the function $f(x)$, the derivative is $Df(x) = \begin{bmatrix}f_x\end{bmatrix} =\begin{bmatrix}\frac{df}{dx}\end{bmatrix}$, with differential $df = f_xdx$.

- For the function $f(x,y)$, the derivative is $Df(x,y) = \begin{bmatrix}f_x&f_y\end{bmatrix}$, with differential $df = f_xdx+f_ydy$.

- For the function $f(r,s,t)$, the derivative is $Df(r,s,t) = \begin{bmatrix}f_r&f_s&f_t\end{bmatrix}$, with differential $df = f_rdr+f_sds+f_tdt$.

- For the function $\vec r(u,v)$, the derivative is $D\vec r(u,v) = \begin{bmatrix}\vec r_u&\vec r_v\end{bmatrix}$, with differential $d\vec r = \vec r_udu+\vec r_vdv$.

Task 15.1

Let's practice using the definitions above. For each function below, (a) compute and label all relevant partial derivatives. Then (b) write the differential $df$ as a linear combination of the partial derivatives. Then (c) write $df$ as a matrix product. Finish by (d) stating the total derivative $Df$ of the function.

- $f(x,y)=x^2y$ [Clearly label all 4 things you were asked to find, namely (a) all partials, (b) $df$ as a linear combination, (c) $df$ as a matrix product, and (d) the derivative $Df$.]

- $f(x,y)=x^2+2xy+3y^2$

- $f(x,y,z)=3xz-x^2y$

Task 15.2

The gradient of a function $f(x,y)$ is itself a function. When we compute the partial derivatives of the gradient, we obtain vectors instead of numbers. This task has you examine the differential, partials, and derivative of the gradient of a function. We'll soon see that the derivative of the gradient is precisely the key to classifying maximums and minimums of a function.

The function $f(x,y) = x^2+3xy+2y^2$ has the gradient $\vec \nabla f = (2x+3y,3x+4y)$. This is the vector field $$\vec F = (2x+3y,3x+4y).$$

- Find the differential $d\vec F$ and write it as the linear combination $$d\vec F = \begin{pmatrix}?\\?\end{pmatrix}dx+\begin{pmatrix}?\\?\end{pmatrix}dy.$$

- Rewrite the above differential as a matrix product, so fill in the blanks below. $$d\vec F = \begin{pmatrix}?&?\\?&?\end{pmatrix}\begin{pmatrix}?\\?\end{pmatrix}.$$

- Clearly label the two partial derivatives $\frac{\partial \vec F}{\partial x}$ and $\vec F_y$.

- State the total derivative $D\vec F(x,y)$ (it should be a 2 by 2 matrix). [Note: We also write the derivative of the gradient as $D^2f(x,y)$, or $D\vec\nabla f(x,y)$, and call the resulting matrix the Hessian of $f$. Some people use the notation $\vec \nabla ^2 f$ for the Hessian, though this notation also gets use for the Laplacian $\vec \nabla \cdot (\vec \nabla f)$, which is a very different quantity.]

- The function $f(x,y) = xy^2$ has gradient $\vec F = (y^2, 2xy)$. Repeat the above to obtain the differential of $\vec F$ (as a linear combination, and in matrix form), the partials of $\vec F$, and the derivative $D\vec F(x,y)$.

Task 15.3

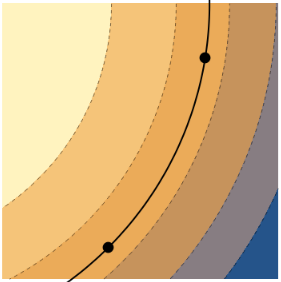

Suppose a rover moves along the level curve of a function $f(x,y)$ following the path $\vec r(t)=(x,y)$. An example of such a scenario is shown below (note that lighter colors correspond to greater outputs of $f(x,y)$. )

Label the dots $A$ and $B$ (it doesn't matter which you label $A$ or $B$). Our goal is to prove that the gradient of $f$ is normal to level curves.

- At each dot in the picture on the right, draw a vector that represents a possible option for $\ds\frac{d\vec r}{dt} = \left(\frac{dx}{dt},\frac{dy}{dt}\right)$.

- Suppose $\vec r(0)=A$ and $\vec r(1)=B$. If we know that $f(\vec r(0)) = 7$, then what is $f(\vec r(1))$? Explain.

- As the rover moves along $\vec r(t)$, how much does $f$ change? Use this to give a value for $\ds\frac{df}{dt}$?

- Explain why $\vec \nabla f$ and $\ds\frac{d\vec r}{dt}$ are orthogonal at any point along the level curve. (Hint: Add $dt$ to the denominators of the the differential $df = f_xdx+f_ydy$ , and then write the differential as a dot product. Since we are on a level curve, we know the value of $\ds\frac{df}{dt}$.)

- At point $A$, draw a vector that points in the same direction as $\vec \nabla f(A)$. Use your work above to explain why the gradient of $f$ must be normal to the level curve.

Task 15.4

The last problem for prep each day will point to relevant problems from OpenStax. Spend 30 minutes working on problems from the sections below.

- Return to any of the previous day's OpenStax problems to locate extra practice.

Day 15 - In class

Brain Gains (Rapid Recall, Jivin' Generation)

- For the function $f(x,y) = \sin(3xy^2)+5x^3$, compute the gradient $\vec \nabla f(x,y)$ and the total derivative $Df(x,y)$.

- For the vector field $\vec F(x,y) = (2x+3y, 4xy^3)$, compute the differential (as a linear combination of partial derivative), state $\frac{\partial \vec F}{\partial y}$, and then state the total derivative $D\vec F(x,y)$.

- For the function $f(x,y) = x^2+4y^2$, graph the level curves that passes through the points $(0,1)$ and $(0,2)$.

- To your plot above, add the gradient at the points $(0,1)$ and $(0,2)$, as well as a few other points along the curves you drew.

Group Problems

- Let $f(x,y,z) = 9x-4yz^3+3xz - y^2$.

- Compute $f_x$ and $\frac{\partial f}{\partial z}$.

- State $\vec \nabla f(x,y,z)$ and $Df(x,y,z)$.

- Let $f(x,y) = x^2-9$.

- Construct a contour plot of $f$. (The contour corresponding to $f=0$ is a great start. Would $f=5$ or $f=-5$ be simpler to add to your plot? You get to pick values for the output that help. )

- At various points $P$ in your plot, add the gradient $\vec \nabla f(P)$.

- Construct a surface plot of $f$.

- Let $f(x,y) = 4-4x^2-y^2$.

- Construct a contour plot of $f$. (Contours corresponding to $f=0$ and $f=4$ are a good start. )

- At various points $P$ in your plot, add the gradient $\vec f(P)$.

- Construct a surface plot of $f$.

Day 16 - Prep

Learning Target Checkoff

A learning target quiz will appear in I-Learn. Complete and submit the quiz before the due date.

|

Sun |

Mon |

Tue |

Wed |

Thu |

Fri |

Sat |